The Body as Archive, Archiving One’s Self

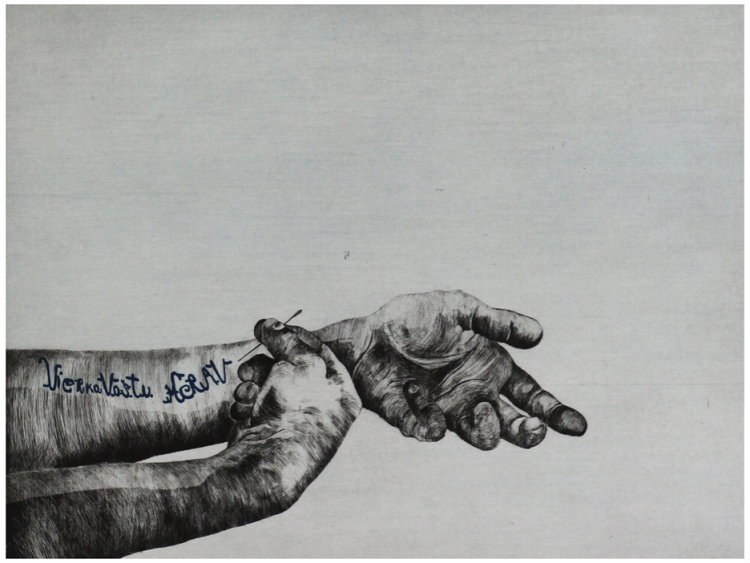

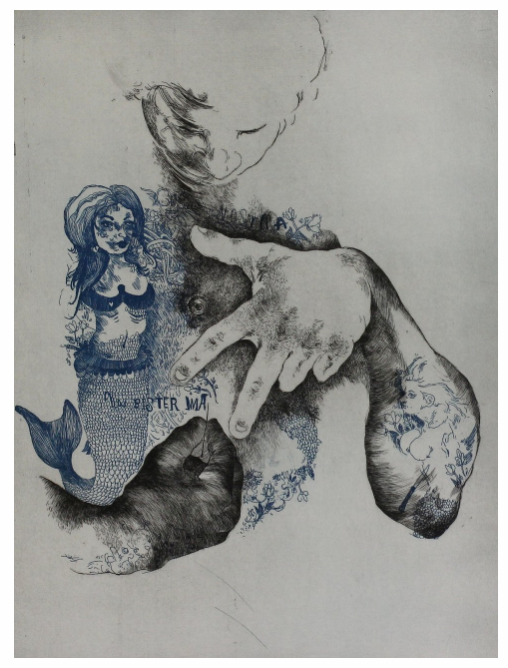

Robert Gabris: Vierka vastu merav [Vierka, I Die for You], The Blue Heart series, 2014, copper engraving on paper

Meghan Forbes considers the work of RomaMoMA as related to memory production and preservation, through the process of recording, archiving and exhibiting. This essay emphasises the relevance of the new museum as a model for an anti-racist, decolonial museum practice so needed in our contemporary moment. She also considers the work of one artist who was featured in RomaMoMA’s first online exhibition, Robert Gabris, which likewise powerfully foregrounds an archival impulse in its subject matter.

RomaMoMA in its early incarnation functions simultaneously as a digital, and dispersed museum. As an online exhibition space, and a series of networked installations in galleries across Europe, with a home base in Berlin, it powerfully embodies a diasporic imperative. In this pluralistic way, it aspires to enter the field of vision of those who might not otherwise seek it out, and at the same time, has the potential to reach communities for whom this work is urgent and essential.

The new museum — which calls for concrete, accountable action from dominant cultural institutions in Europe to join in an effort to increase representation of Roma arts and culture — also offers a salient model for reckoning with a racist past and present. From where I write in New York, in the midst of the current coronavirus pandemic, and at a critical moment in the Black Lives Matter movement, it remains to be seen if and how art museums here will heed the most recent (of decades-long) calls to meaningfully adjust their acquisition and exhibition strategies, as well as hiring practices and treatment of Black and Brown employees, and become more welcoming spaces for local audiences. At this juncture, the creation of RomaMoMA seems to me a powerful and liberatory call for action, with relevance on both sides of the Atlantic, and if it manages to operate within an egalitarian, non-hierarchical framework, could succeed where MoMA so far has not.

In the RomaMoMA manifesto, the question is asked: “How will the Roma people and Roma contributions become recognised in the (art-) history of Europe?” It would seem that the establishment of RomaMoMA itself is intended to be one possible answer to this. Following Aleida Assmann’s framing of remembering and forgetting as it relates to processes of exhibiting and archiving, the museum is potentially a space of active remembering, and thus canon building.[1] RomaMoMA can address gaps in the archive precisely by making them a point of discussion and subject of critique on its blog and in its exhibition and event programming.

On the flip side of Assmann’s charting, active forgetting takes the form of material destruction, negation, taboo.[2] Previous posts on the RomaMoMA platform address how this is a present-day circumstance that simultaneously works against the memory-building impulse of the new museum. Anna Lujza Szász, for instance, points out that when funding for the Amaro Drom magazine in Hungary was pulled, its own archive of photographs was lost. And Maria Lind describes the XXX initiative that fights another kind of erasure, that of incorrect object labels and provenance attributions (the process of ascribing provenance being a major way in which a colonial, and white Supremacist history of art has been constructed in the first place[3]).

ERIAC’s executive director Tímea Junghaus wages a call for a “transnational museum” precisely in this moment where increased cultural activity is met with state resistance: “Against the growing number of Roma cultural events around Europe, the situation of cultural rights has deteriorated significantly: Roma creative production is in worse circumstances than it was in the 1970s, with Roma tangible cultural heritage in actual danger, completely invisible and inaccessible to the public”. At the same time, the commitment to the creation of a RomaMoMA museum offers a counter to regressive, racist, and nationalist politics in Europe. It resists erasure and the violence of a forced forgetting, by offering multiple kinds of spaces for creating and exhibiting art, as well as community building. As it aims to build relationships across powerful institutions, it must also be careful not to reify the established power relations that have rendered the current conditions of exclusion.

An early example of the RomaMoMA project is the online exhibition, Performing the Museum, launched on 8 April 2020, curated by Denisa Tomkova, and including works by artists Oto Hudec, Daniela Krajčová, Emília Rigová, Selma Selman, Robert Gabris and Marcela Hadová. By centring narratives that represent and reflect on various aspects of Roma life, depicting joy and pain, it presents a kind of exhibition so rarely seen in Europe.

The work of Robert Gabris in this online exhibition, a series entitled The Blue Heart from 2014, treats the physical body as an archive. A set of copper engravings illustrates individual body parts – hands and feet, chest and head, a set of ears, the heart — that are accompanied by tattoo markings and text, typically rendered in blue. Several images capture the process of inscription, as a hand holds a needle turned towards its own body, producing a work of art on the (non-white) canvas of the skin. It is a layering that lays bare the artistic process — by documenting the act of scratching an image into oneself, the works on paper likewise call up the etching technique used in creating these final images.

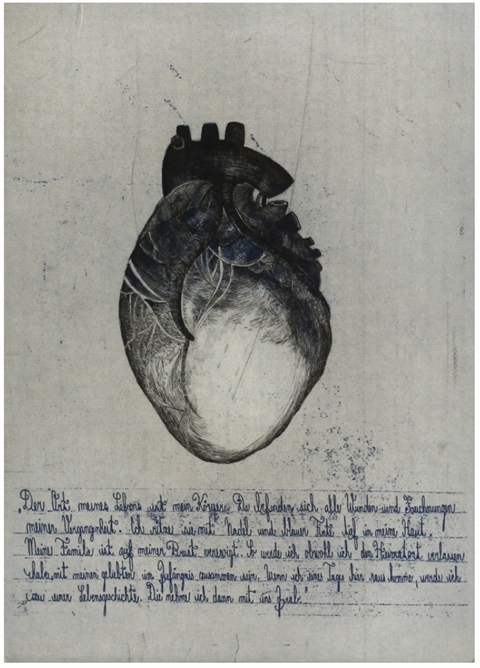

Robert Gabris: Na bister du [Forget Me Not], The Blue Heart series, 2014, copper engraving on paper

The series is inspired by Gabris’ personal history, as his father spent years as a tattoo artist in prison. In one etching that includes at its centre a large, swelling organ of the heart, Gabris records his father’s speech (printed in German) in lines that run along the bottom: “The place of my life is my body. It is there that can be found all the wounds and drawings of my past. I carve them deep into my skin with needle and blue ink”.[4] In a 2017 report issued by the European Roma Rights Centre in Budapest, it was found that in Slovakia, where Gabris is from, “it is 40 times more likely that a police unit will be appointed to a Roma community than to a non-Roma community”.[5] In its subject matter, The Blue Heart series, which collects stories from a Roma village in Slovakia, both touches on the structural bias linked to higher rates of incarceration amongst the Roma population (which is documented to be the situation across Europe) and tells a personal story of love and separation. Gabris’ intricate illustrations stand as formally beautiful objects, as they do the double work of drawing attention to societal issues affecting one community in Slovakia while gesturing towards a more endemic level of violent bias.

Robert Gabris: The Blue Heart, The Blue Heart series, 2014, copper engraving on paper

The labour of collecting and sharing stories inherent to The Blue Heart series is also a process of active remembering. Both Gabris’ illustrations, and the actual bodies that bear the real tattoos, are engaged in a process of recording. Exhibiting this work — which has been previously shown in gallery spaces in Vienna (where Gabris resides), Bratislava, and several other cities — is the next step in activating memory, by making these stories visible to a wider public.

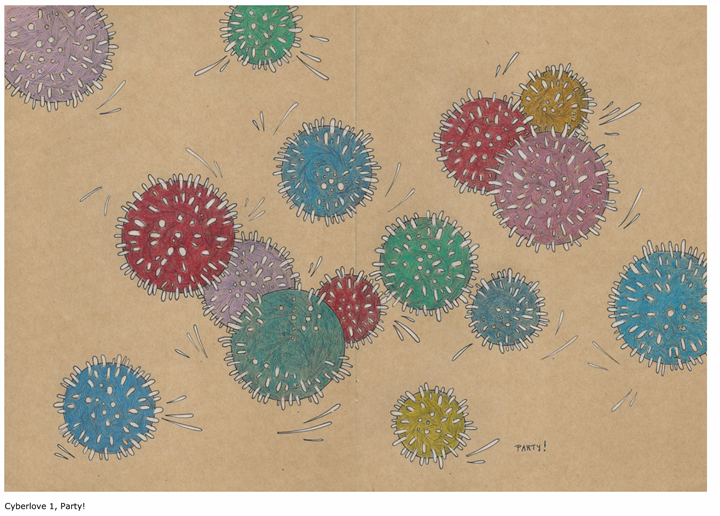

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Gabris has also created a new series called Cyberlove 2, which he defines as an impulse to “museumize a collection of selfishness, loneliness and a life in isolation”. It builds on previous work that creates an ironic portrait of the world of online dating, and is also a critique of the limited language available and pervasive racism on these apps. As in The Blue Heart series, anatomical parts are also shown extracted from the rest of the body in these playful if cynical drawings. Here, it is the phallus and vagina that are the main objects of attention, which seem to have a life of their own (or rather, are the life of the party), but in some instances, the physical body is referenced simply as a colourful palette of germs coming into contact, alluding to a new sort of risk inherent in desire during the era of coronavirus.

Robert Gabris: Cyberlove 1, Party!, Cyberlove 2 series, 2020, coloured pencil on paper

While The Blue Heart series was featured in RomaMoMA’s first online exhibition during quarantine, an online magazine created by the VUNU Gallery in Košice, called New Translation, featured several of these new works from the Cyberlove 2 series, as well as those which had been on view at a solo exhibition at the Šopa Gallery, also in Košice, which had opened in February 2020. This agile and adaptive movement between the digital and the physical space has been a necessary mainstay of this year, and in some ways, it has democratised access for viewers, and given artists a wider audience.

On the other hand, the role that the Internet has played in making art visible during the pandemic does not preclude the importance and necessity of physical exhibition spaces. Again, Junghaus highlights the importance of ERIAC as an institution in as much as it has four walls, so that it can meet “the actual need and desire of the European Roma community: actual space(s) built with purpose, equipment and expert knowledge, with high standards for music recording, talent scouting, art production, public education, printing, concerts, theatre performances, exhibitions, etc”. If ERIAC and RomaMoMA are able to support Roma-led activities that provide open and inclusive platforms for the community in whose name it operates, it can generate a movement towards a radically visible (self-)representation.

Indeed, online exhibitions and programming can supplement, but should not replace, those brick and mortar sites of exchange in which we can come into community once it is safe to do so from a public health perspective, to enjoy the tactility of the objects, to learn and bear witness together. RomaMoMA is an intriguing new model in this regard. It is high time for major cultural institutions in Europe and the United States to make better use of the spaces that they already have, or hand them over to those who will.

Meghan Forbes is a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Leonard A. Lauder Research Center for Modern Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Previously, she was the C-MAP Fellow for Central and Eastern Europe at MoMA. Meghan’s writings have appeared widely, in both scholarly and popular publications, such as ArtMargins, Umění/Art, Hyperallergic and post: notes on art in a global context. She has also contributed to monographs and exhibition catalogues on the artists Alice Trumbull Mason, Toyen and Władysław Strzemiński. Meghan is the sole editor of International Perspectives on Publishing Platforms: Image, Object, Text (Routledge, 2019) and co-curator of BAUHAUS↔VKhUTEMAS: Intersecting Parallels (Museum of Modern Art Library, 2018). She is the founder and co-editor of harlequin creature, a not-for-profit arts and literary imprint of handmade books and magazines established in 2011.

[…] Next Blog Entry […]

[…] Previous Blog Entry […]

This is some nice material. It took me a while to finally find this site but it was worth the time. I noticed this content was hidden in google and not the number one spot. This webpage has a ton of high-quality stuff and it doesnt deserve to be burried in the search engines like that. By the way I am going to add this web page to my list of favorites. Have you considered promoting your blog? add it to SEO Directory right now 🙂 http://www.links.m106.com