MODEST COPERNICAN REVOLUTIONS

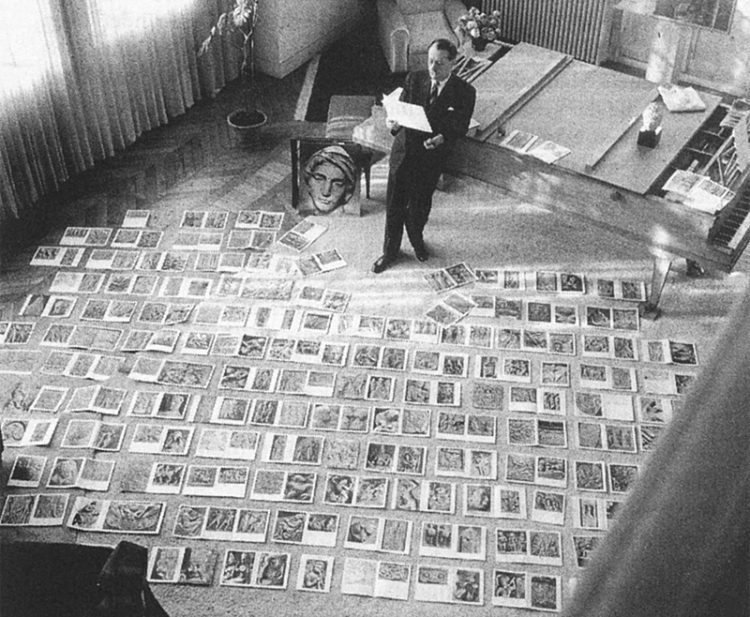

“André Malraux chez lui” © Maurice Jarnoux – Museum without walls concept

Imagine a presentation of Rosa Taikon’s silver jewellery at Hälsinglands Museum in Hudiksvall, a solo exhibition with Malgorzata Mirga Tas’s textile paintings at the Galerie für zeitgenössische Kunst in Leipzig, and a show with Robert Gabris’s drawings at Salonul de Proiecte in Bucharest. Then there is a retrospective of Ceija Stojka and her Holocaust memory paintings at Belgrade’s Museum of Contemporary Art, and at the Sami Centre for Contemporary Art in Kárašjohka a screening series is held with Selma Selman. In addition, envision that the Museum of Romani Culture in Brno has invited Joar Nango to make an installation, and that ERIAC in Berlin has dedicated one wall to the work of Emília Rigová. All these projects are on view at the same time. And all are part of one single museum –RomaMoMA.

Selma Selman, performance “You have no idea” 2016 – Emília Rigová, series “Crossing B(l)ack” 2017

At the forefront of contemporary institutional and curatorial work, this distributed museum follows the pattern of Roma life as it exists in most countries of Europe. The institutions that have committed to make RomaMoMA happen are radically different, ranging from regional museums of history and ethnography, private foundations and municipal venues, to national art museums and self-organised spaces. They gather around a shared concern with Roma art and culture, and a desire to showcase and discuss it, within the broader context of modern and contemporary art, under the economic, social and political circumstances of our time. They commit to devoting a room or a wall to RomaMoMA for a minimum of three years, to safeguard continuity and situatedness, allowing the museum to evolve and sediment over time. Each instance, every act of making the art go public, can stand on its own, and be read in the context of that institution, its context and legacy. Like nodes in a network. But each instance can simultaneously be seen as a patch, next to many others, in the rich quilt called RomaMoMA, which will gently envelope Europe and offer some warmth.

The idea of a distributed museum is not entirely new. André Malraux, writer and Minister of Culture in France, famously developed his ideas around “the museum without walls” in the 1940s. With the reproductive technologies, which were new at the time, art from all periods and from all geographies could be brought together as reproductions. This generated a myriad of new readings of art, and it helped to widen the scope of what can be thought of as art. In Malraux’s vision, applied arts and so-called folk art would be included in the sphere of fine arts canonised by formalised art history. Anybody with the means to purchase or otherwise acquire books, postcards and posters could present their own version of art history. This could be done on the floor, as the writer did in his own study, or on the walls in an appropriate space. Anyone could curate their own mini-exhibitions, thanks to the abundance and easy access to “replicas”. Nevertheless, the new proximity was based on a certain homogenisation, and a subsequent levelling, which increased the degree of connectivity and potential for fresh relations.

The museum without walls made art “the common heritage of mankind”[1]. Even more importantly for our discussion around RomaMoMA, “the museum without walls” was essentially a scattered and yet networked museum, albeit virtually and unbeknownst to anyone but the individuals who curated their personal exhibitions. RomaMoMA aims for precisely this kind of connectivity and fresh relations, connecting the dots in a previously blurry, and even invisible, picture. It will be based on sharing knowledge about what is already there, not unlike how the visionary artist, architect and designer, Frederick Kiesler introduced the idea of art museums sharing their collections in the 1920s. He anticipated how, in the future, museums would make available for viewing works on display, as well as in storage, with other institutions and individuals, through electrical screens that would work through the telephone lines. A common denominator for Malraux and Kiesler was a desire to make art available to more people than the already converted, which in Kiesler’s case was also expressed in his idea to display art in shop windows. In other words, they sought to propagate new channels and ways to experience art, following in the footsteps of avant-garde artists across the world, comparable in our own time to how we are grappling with screen culture, geographical dispersion and physical distancing. For RomaMoMA, it is about making “Roma culture part of the common heritage of mankind”, to paraphrase Malraux.

The fact that art institutions do things together is not unusual (albeit not as usual as one could wish), but it is rare that collaborations today go beyond common funding applications and acting as stations on an exhibition tour. Among the notable exceptions are Arts Collaboratory, a network with small art institutions in the global south; L’Internationale, with a handful of major public art museums in Europe, plus a non-collecting institution in Istanbul; and Cluster, with small and medium-size art organisations in suburban areas in Europe and in Israel (Tel Aviv). They stimulate knowledge exchange and jointly develop research, exhibitions and publications, often as chapters that draw upon one another, in order to create synergy effects beyond monetary and reputational value. To some degree, they are practicing institutional solidarity. There are also examples of how during the last decades some art museums have co-purchased works for their collections, for instance, the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, and Tate Modern in London.

Similarly, RomaMoMA will actively seek to connect the various dislocated parts, which are radically different from one another, and to draw from modern and contemporary art by artists with a Roma background, and others. Likewise, it will highlight a tangible and intangible heritage, which already exists in collections and archives across the world. An initiative, called XXX, has already been taken, through which objects and other material included in established repositories will be assembled to precisely highlight their Roma history. In order to do so, it is frequently necessary to correct erroneous labels and to re-attribute their provenance, to properly acknowledge their identity. Each separate project that is part of RomaMoMA will be embedded locally, among Roma individuals, groups and beyond, while those projects are also actively connected to one another, trans-locally, like Malraux’s “museum without walls” and Kiesler’s “screen museum”. They will be complemented by regular online conversations and lectures with artists, curators and other scholars and experts, and will be combined with an active presence on social media and other online platforms.

Numerous artists, theoreticians and others have tried to bury the museum, many times over, considering it outdated and stale. But they have failed. Indeed, the museum has often been employed as a tool of control and repression, and yet, it has an admirable ability to survive as a format. Despite war, revolution, famine and other upheavals – across centuries. The allure is at least partly connected to the fact that the museum is so malleable, contrary to popular perception, over time, and in a wide variety of contexts. It has been moulded to fulfil various functions and aspirations, and as a phenomenon and an idea, “the museum” remains firmly established in most people’s minds. As can be expected, this elasticity is appreciated by artists, who in the 20th and 21st centuries have paved the way for how to deal productively with “the museum”.

There is Marcel Duchamp’s cheeky mini museum, la boite-en-valise, or the museum in a suitcase, with miniature replicas of a number of his own works. Marcel Broodthaers’s critical and yet playful Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles, was a traveling museum with idiosyncratic dealings with the eagle as a symbol of greatness and power, as it appears in nature, on coins, as figurines, etc. For her part, Mierle Laderman Ukeles made the cleaning of the museum, the maintenance of the monument, into the actual art-work. It was a “performance” made by her, pointing out the necessary but invisible work carried out mostly by working-class women. Self-institutionalisation has played a not minor role in these projects, as well as in many related ones: as a recent graduate from the art academy in Tallinn, Flo Kasearu, turned a dilapidated wooden house she had just inherited into the art project “The Flo Kasearu House Museum”, while in Gdansk a small group of artists squatted an office building in the shipyards to stage art projects, calling it “Wyspa Institute of Art”. Tensta Museum[2] was a curated project of Tensta konsthall, which for seven years dealt with the history and memory of this Stockholm suburb by “playing museum”. Art projects, archival material related to the neighbourhood, discussions on urban issues and thematic tea and coffee salons are some examples of what made up the museum.

Radically inclusive, RomaMoMA, this brash proposal, is not content twisting the conditions of a museum: it is turning perspectives upside-down. Like Marcel Duchamp’s urinoir, which transformed a mundane prefabricated object into an artwork by placing it into an art context and naming it art. And like Piero Manzoni’s Pedestal of the Earth, in which the artist made a pedestal for the globe by producing a podium like the ones used for sculptures in museums – but with its bottom pointing to the sky. The globe becomes the sculpture on top of this miniscule support structure. By the same token, Hreinn Fridfinnson’s cottage on a lava field in Iceland keeps the interior decoration – wallpapers, curtains, potted plants, etc. – on the exterior, making the entire world the home of the cottage dweller. We could call them modest Copernican revolutions in art, curating and museology. In the case of RomaMoMA, work by artists from Europe’s largest minority, and issues, attitudes and methods pertaining to discourse around it, will be made visible by this uniquely distributed, and at the same time intensely situated, museum.

Maria Lind is a curator, critic and curator, currently based in Moscow, where she is Councillor of Culture at the Embassy of Sweden.

[…] for the Amaro Drom magazine in Hungary was pulled, its own archive of photographs was lost. And Maria Lind describes the XXX initiative that fights another kind of erasure, that of incorrect object labels […]