Painting Back: Decolonization Through Art

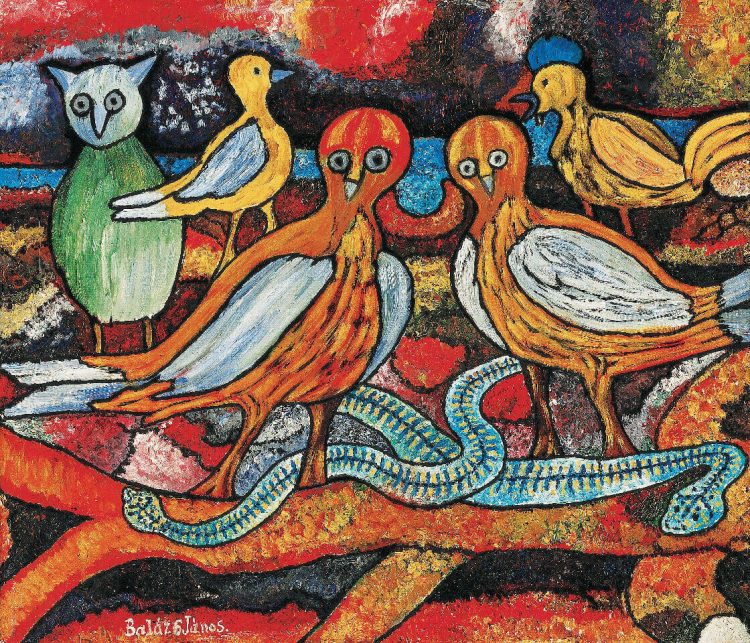

János BALÁZS, Birds, c. 1972, oil on canvas, Horn Collection, Budapest, exhibited at “ONE DAY WE SHALL CELEBRATE AGAIN” / ROMAMOMA @DOCUMENTAFIFTEEN

In 2022, at the fifteenth edition of documenta in Kassel, I witnessed an interesting conversation between two visitors standing in front of a large-scale and impressive work by Tamás Péli. ‘Péli studied at the Koninklijke Academie van Beeldende Kunsten in The Hague,’ one of the two women read out from the label. The other immediately interrupted her: ‘Oh, so this work is no longer part of the exhibition with the Roma artists?’

It is safe to assume these two visitors were looking specifically for the Roma artists exhibited in the Fridericianum, one of the main venues of documenta. The interest was there, but so were the expectations: they were looking for a romanticized display of the self-taught artist, they were looking for ‘primitive art,’ for exceptional artistic talents from a marginalized minority who, far from the corrupt art market and the academy, have found their voice and could now be regarded with curiosity as ‘the foreign.’ The white gaze. White fantasies.

‘Neither the term Orient nor the concept of the West has any ontological stability; each is made up of human effort, partly affirmation, partly identification of the Other,’ wrote Edward Said in the preface of the 2003 edition of his Orientalism (Said 2003, xvii). It follows that Europe must abandon both the idea of the Orient and the idea of the West if a sincere form of dialogue is to take place. Homi K. Bhabha, another theorist of postcolonialism, proposed the notion of the ‘Third Space’ for such a dialogue. For Bhabha, cultures are dynamic, fluid and can be powerful in different ways, and their encounter cannot but lead to power imbalances. Bhabha distinguishes between ‘cultural diversity’ and ‘cultural difference.’ While for him, ‘diversity’ implies that cultures are clearly defined and static in nature—which they are not in reality—‘difference’ means not only the difference of cultural practices and customs, but the process of translation and confrontation that gives rise to new cultural practices (Bhabha 1994, 49–50). In order to overcome the dichotomy of own vs foreign, we have to pass into the ‘Third Space’ and create something new together (Bhabha 1994, 53–56).

This text will look into what artistic and curatorial strategies can help to overcome Orientalism and to search for the ‘Third Space.’

The work by Tamas Péli in front of which the two visitors stood in Kassel was part of the exhibition, One Day We Shall Celebrate Again: RomaMoMA at documenta fifteen, which had been co-commissioned by OFF-Biennale Budapest and the European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture (ERIAC). The other featured artists were Daniel Baker, János Balázs, Robert Gabris, Sead Kazanxhiu, Damian Le Bas, Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, Omara, Selma Selman and Ceija Stojka, outstanding practitioners who have all earned their place in the art world. Rather than any of the numerous off-spaces occupied by documenta, the works were put on display in the central venue, the venerable Fridericianum. The message this sent was that the Roma are an elementary part of European, even global, cultural history, as well as of the societies in which they live.

The increasing visibility of Romani artists, the international success of individual female practitioners such as Małgorzata Mirga-Tas or Selma Selman, occur at a time when decolonization is being talked about in the mainstream. A time when museums are slowly beginning to take a critical look at their own collections. Their role as the guardians of the grail of knowledge is increasingly called into question by decolonial, anti-racist, anti-Romaphobic, queer and feminist movements and struggles. Since Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy’s report, The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Towards a New Relational Ethic (Sarr–Savoy 2018), and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, museums, collections, institutions and biennials have faced increased pressure to review Eurocentric perspectives and to give voice to indigenous and marginalized groups. Colonialities, i.e. colonial thought patterns and structures that are still in effect today, are increasingly being addressed and exposed as forms of racism and fantasies of white supremacy, which affect all marginalized groups, including the Roma. But there is still much to be done.

Art plays a major role in these struggles. Artists are ‘painting back.’ They resist objectification and become the acting subject. As early as the 1990s, The African American writer Toni Morrison proposed, in relation to the Black population of the US, ‘to avert the critical gaze from the racial object to the racial subject; from the described and imagined to the describers and imaginers; from the serving to the served’ (Morrison 1994, 125).

I want to look at different strategies of decolonizing the museum, rethinking art history and disrupting exhibition practices through the visibility of Romani artists.

‘ERIAC aims to be the promoter of Romani contributions to European culture and talent,’ reads the website of the organization (ERIAC). It fulfils this task with flying colours. There is hardly a major renowned art event in Europe without the presence of artists from the Roma communities, from documenta fifteen in Kassel, through Manifesta 14 in Prishtina, to the 59th Venice Biennale. This is good and important, because the artistic work of the Sinti and the Roma, and their role in European art history, still do not receive sufficient attention. Fighting stereotyping, antiziganism and discrimination through art is not only a successful strategy, but, says feminist thinker Nicoleta Bitu, a necessity as well: ‘You cannot fight racism without making reference to history and the arts’ (RomArchive 2019, 8).

There are different strategies available: let us call them ‘Claiming the Space,’ ‘Disrupting the Museum’ and ‘Stepping In.’

The Roma Pavilion at the 59th International Art Exhibition of Venice was an example of ‘Claiming the Space.’ This is the fourth Roma Pavilion at the Venice Biennale (after 2007, 2011 and 2019) and, as in its previous instance, it was commissioned by the European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture. In 2022, the pavilion presented The Abduction from the Seraglio, a solo exhibition by artist Eugen Raportoru and curator Ilina Schileru, both from Romania. The room-filling installation transformed the exhibition space into a flat. The living room, kitchen and bedroom were furnished and carpeted, and there were cleverly curated paintings on the walls (acquired at flea markets, among other places) that alluded to key icons (people, myths) of European cultural history. The Roma Pavilion celebrates the Roma Art label as a political statement and tool of empowerment. It follows the concept of what Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak calls strategic essentialism (Spivak 1993, 20). The critic introduced the concept in a bid to help marginalized groups to gain visibility through self-representation and thereby to draw attention to their specific problems. In current debates, critics point out the problematic nature of all identity politics, as something that focuses on differences rather than commonalities, strengthening social divisions rather than easing them. I would like to counter this criticism of identity politics with a simple and convincing analogy offered by the German thinker, Carolin Emcke: Imagine that people with a height of 180 cm have no access to opera. 180 cm tall individuals will not immediately recognize this as a form of exclusion, but a closer look reveals a structure, the fact that height is the reason for the denial of access. So the only way to point out structural discrimination against people who are 180 cm tall is to point out the common characteristic that lead to this discrimination—different though otherwise they are (Wegner–Amend, 2019). Identity politics becomes redundant when all people are truly equal in society. The Roma art label is thus a temporary essentialization of Romani artists that serves to abolish itself one day, the day when Romani arts and cultures have become a self-evident part of art history.

‘Disrupting the Museum’ is another interesting strategy. Barvalo, the exhibition of the Mucem (Museum of Civilizations of Europe and the Mediterranean) in Marseille, was a case in point. The exhibition was dedicated to the history of the Sinti and the Roma in Europe, their civil rights movement, diversity and contemporary art. It showed 200 works from public and private collections, with context carefully chosen and presented in multiple media. Marseille’s spectacular museum welcomed hundreds of people every day, offering an experience that combined art and learning. One of the exhibits was the Musée du gadjo (Gadjo Museum), a work by Gabi Jimenez, who inverted Said’s ‘Orientalism’ and took an ironic look at the Gadjo, the non-Roma. His installation was modelled on the classic ethnological exhibition, with artefacts and information on the history, origin and culture of the Gadjos, a supposedly homogeneous ethnic group. Jimenez even fashioned a diorama of the ‘typical’ Gadjo living room. The installation highlighted the absurdity, as well as the epistemological violence, of the ethnographic tradition. Cultural essentialization, which robs a group of any heterogeneity and diversity, is still practised in museums of ethnology, and is dismantled in Jimenez’s work through humour and sarcasm. The laughter, though, gets stuck in the visitor’s throat.The presence of a wide variety of contemporary Romani artists at all the important art events in Europe is in a way also part of the strategy of ‘Disrupting the Museum.’ This is because in this way, the desire for folklore and self-taught artists remains dissatisfied and there are no aesthetic brackets into which the various artists are forced. Not satisfying expectations can be an effective act of resistance.

Lastly, I would like to turn to a strategy that in a sense points to the future: ‘Stepping In.’ At the 59th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Małgorzata Mirga-Tas was given the run of the Polish Pavilion. The exhibition was curated by Wojciech Szymański and Joanna Warsza. It was the first time in the 120-year history of the Biennale that a country had been represented in its pavilion by a Romani artist. With her project, Re-enchanting the World, the artist claimed a place for the Roma in European cultural history. Featuring twelve large-format textiles, the truly enchanting room-sized installation was inspired by those Renaissance frescoes with astrological imagery that can be seen in the Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara. This European iconography was expanded by Mirga-Tas to include the history, experiences, knowledge and artistic creations of the Roma. The fact that a Romni should represent the Poles in their national pavilion is, of course, a powerful political statement, but it is also simply the acknowledgment of a great artist—who happens to be a Romni. I read this as a promise of a future in which the Roma are a natural part of art history. A future in which their authorship and influence on European cultures are recognized, a time when no bias informs their presence in collections and exhibitions. A future in which we meet in the ‘third space’ between cultures to create something new together. Until this becomes a reality, Roma artists will continue to resist through art—will keep painting back.

References:

Bhabha, Homi K. (1994), The Location of Culture (London: Routledge).

ERIAC, https://eriac.org/about-eriac/, accessed 1 Sept. 2023.

Morrison, Toni (1992), Playing in the Dark (New York, Vintage Books).

RomArchive (2019), Press Kit, https://blog.romarchive.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/RomArchive_PressKit_190221.pdf.

Said, Edward W. (2003), Orientalism (1979), 25th Anniversary edition (New York: Vintage Books).

Sarr, Felwine and Savoy, Bénédicte (2018), The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage. Towards a New Relational Ethic (Paris: Ministère de la Culture).

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty (1993), ‘In a Word: Interview,’ Outside in the Teaching Machine (New York: Routledge), 1–24.

Wegner, Jochen and Amend, Christoph (2019), ‘Carolin Emcke, wie finden wir Glück?’ Alles Gesagt? Der Interview podcast (podcast), https://open.spotify.com/episode/0zB1BQQGh1Jrqo1FLI4Ceh.

Leave a Reply