From the Pissoir to the Bathtub — Selma Selman Destroys Conventions with Axe and Drill

Selma Selman, Motherboards, Performance 11.11.2023, Gropius Bau, Photo @Eike Walkenhorst

The surface is never simply smooth or clean in Selma Selman’s works. The artist paints on objects such as car bonnets, bathtubs or satellite dishes as naturally as if they were stretched canvases. These objects are then either displayed freely in the room or are carefully arranged on the wall, constantly moving on the border between painting, sculpture and installation. In her works, the past—in the form of art history and cultural memory—merges with contemporary political discourses, including her own ceaseless questioning of existing power relations. Rooted in an avant-garde attitude, Selman’s installations encourage the audience to reflect on conventional values in art and social structures.

The starting point of her latest exhibition at the Gropius Bau, her0 is Motherboard, a series of performances in which she smashes laptops with axes and drills in order to salvage and recycle raw materials from the computers’ motherboards. She uses the short breaks she takes during this physically demanding work to read out quotes from Rudyard Kipling’s The Secret of the Machines (1911), among other works—or rather, to shout them into the faces of the audience. The lyrical subject of the poem assumes the position of a machine, and thus Selman allows her apparent ‘victims’ to speak:

We were taken from the ore-bed and the mine,

We were melted in the furnace and the pit—

We were cast and wrought and hammered to design,

We were cut and filed and tooled and gauged to fit.

(…)

We can pull and haul and push and lift and drive,

We can print and plough and weave and heat and light,

We can run and race and swim and fly and dive,

We can see and hear and count and read and write!

(…)

It is an ode to the machines that can do almost everything as well as, if not better than, humans. At first glance, these worshipful words seem to stand in contrast to the destructive act of the performance. The destruction of machines brings in mind those British workers who called themselves Luddites and attacked and damaged machines during the industrial revolution, at a time of rapid technological development. With their jobs taken away from them and no future in sight, their outrage was understandable. The poem, in which respect for machines and the superior position of humans as ‘creators’ are both emphasized, is a smart choice on Selman’s part, who seeks to question the way the Luddites are cast in history. They were not against machines per se, but stood up for workers’ rights and demanded respect for humans while machines rapidly gained ground. And that is an issue that will certainly continue to be of relevance as we increasingly rely on digital assistants and AI. As they spread, we are both in awe of their far-reaching possibilities, and must confront existential fears and the anxiety over losing control—not unlike 200 years ago.

The dichotomy of man and machine has been a recurring theme in art since the industrial revolution and became increasingly a focus during the avant-garde period. This ambivalent relationship in the 20th century was recently the theme of a major show at the Museum Folkwang in Essen.[i] The exhibition included ‘new representations of man’ by Marcel Duchamp, El Lissitzky and Umberto Boccioni; showed depictions of humans by Otto Dix and George Grosz, which were critically influenced by the horrors of the First World War; presented Rebecca Horn’s playful performances that explored the possibilities of the human body; and involved recent Post-Internet art.

It is evident that Selman’s position is not as extreme or unequivocal as that of the show mentioned. The machines are not depicted as unambiguously evil, nor are they the ultimate saviours of our civilization. They are simply a part of life, just as they are a part of Selman’s artworks. She has a long history of engaging with machines, because her father used to make a living by recovering noble metals from scrap, and she also worked in a scrapyard as a teenager. Perhaps it is thanks to this experience and knowledge that her relationship with the machines and metals she works with is based on respect, and is always changing and fluid: she invests a great deal of time in handling them with care and finding different ways to recycle their parts, but she is not afraid to take on the role of the machine either, by performing the heavy, monotonous task of disassembling computers, cars or washing machines. While most artists engaging with this topic want to transform the human body with the help of new technology and use machines to experiment with flying humans, human-machines or new computer-generated human figures in their art, Selman shifts the perspective and puts the machines in the centre. Rather than placing machines in the service of the human body, she uses the power of her art to re-evaluate machines and allow them to live on after their ‘death.’ This interaction, which resembles more of a symbiosis than an exploitation, is the foundation of her transformative work.

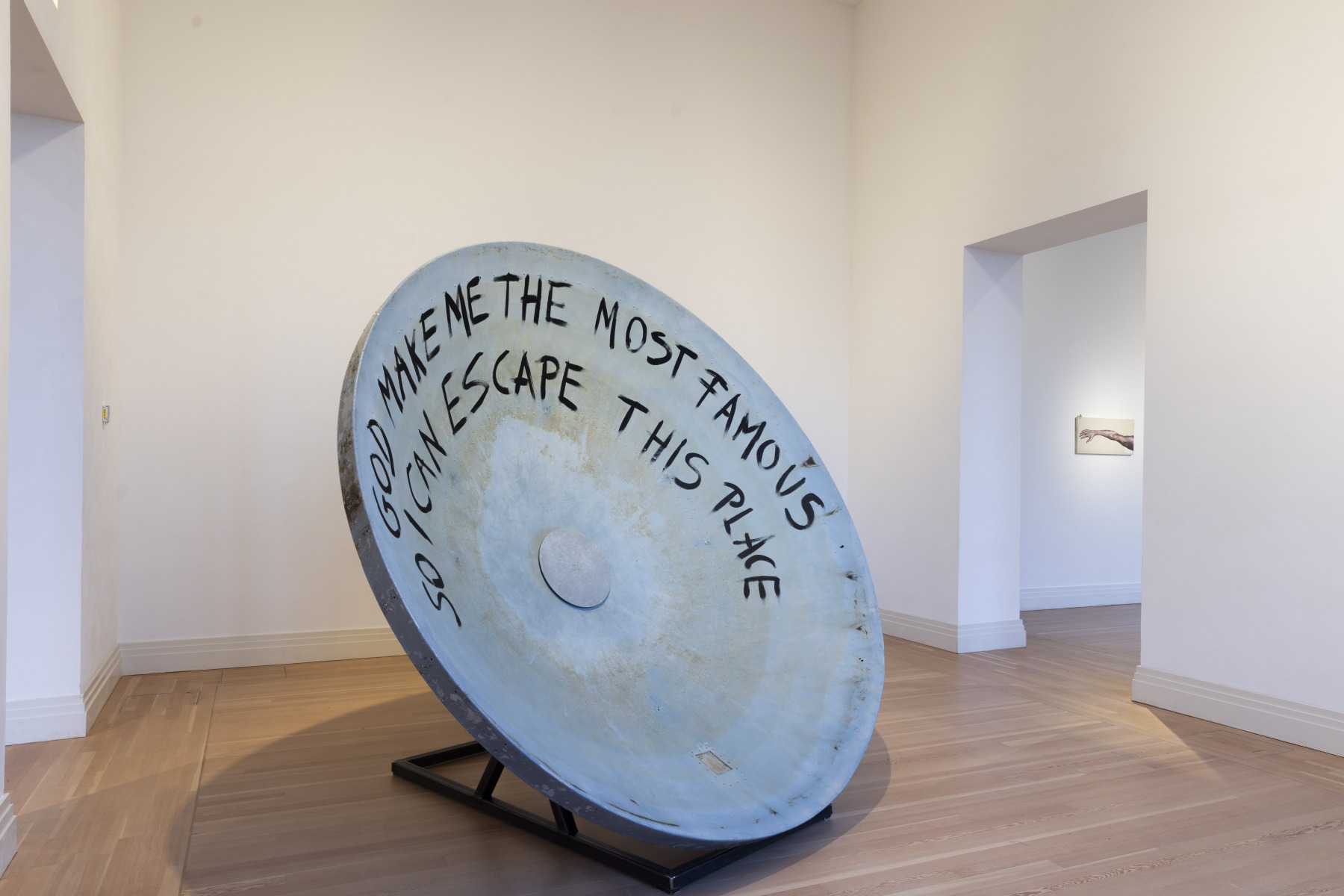

Selma Selman, Satellite Dish (2023), installation view. Courtesy of the artist and Gropius Bau; Photo: @Eike Walkenhorst

The dangerous, dirty and noisy labour of disassembly is central to Selman’s oeuvre, performed in front of the public, often in collaboration with her father and other members of the Roma community in Bihać. It is a very direct and hands-on task, yet it has a symbolic, even ceremonial character. The Motherboards performance in the Renaissance Revival room of the gallery is made complete with the white dress, shirts and gloves worn, and the music played by a sound-designer and a cellist, which complements the sharp clashes of axes hitting the metal. With the radical disassembly of the complex, carefully built systems of computers, it becomes clear that the hard work of deconstructing structures pays off, and can result in the birth of something more valuable. The raw material obtained from the motherboard becomes a sculpture: a golden nail.

Unapologetically engaging with the legacy of modernism, Selman also takes the ‘great masters’ of classical modernism as a starting point. The second room of the exhibition presents Six Pieces of Mercedes Benz: six elements of the disassembled bodywork of a black Mercedes, mounted on the wall, bearing paintings of abstracted female figures whose strikingly long and slender limbs flow into one another. The reddish-brown and purple palette and the frontal presentation of the naked female bodies recall Pablo Picasso’s famous painting, Les Desmoiselles d’Avignon. The angular, geometric shapes of the car parts on the two-dimensional surface of the wall reinforce this impression. This time however, it is not the female body that has been dismantled by a male artist, but a machine that stands for consumerism, both figuratively and concretely. As in a cubist painting, only disjointed parts of the whole (once working) car can be recognized, and in their new function as ‘canvas’ they lend the installation an unusual perspective. Picasso’s 1907 painting is perceived as a turning point in the history of art: reflecting on painting itself and what beauty in art meant, he destroyed old conventions and created – at the time – a new order of thought. Selman’s revisiting of a pivotal moment in art history once again reinforces the transformative character of her art, and encourages the viewer to reconsider conventional thought on themes of her painting: body, gender and social structures.

In a similar fashion, the sculptures she exhibits, Satellite Dish or the Metal Paintings series, evoke the concept of ready-mades—found objects of everyday use that are not usually expected to be presented at an art show. The playful reference to a major landmark in the history of the avant-garde, which started to redraw boundaries and question who could exhibit, what and where, signals that this discussion is still fiercely relevant. In particular, it is her bathtub that can be quickly identified as the feminine counterpart of Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain. In the painting, a female nude lies in a bathtub, with an arm hanging by its side, confidently looking into the eyes of the audience: a self-portrait of the artist, exhibited for the first time. It is accompanied by a sign placed next to the door asking visitors not to take photos of this work. As Selman later explained,[ii] nudity, especially the representation of female nudity, is very rare in the Roma community, and it was the first time she had broken with this cultural convention, which is why she asked us not to disseminate this work.

Selma Selman, Motherboards (2023–ongoing), Golden Nail, installation view. Courtesy of the artist and Gropius Bau; Photo: @Eike Walkenhorst

[i] Der montierte Mensch, Museum Folkwang, 8 Sept. 2019 – 15 March 2020, https://www.museum-folkwang.de/de/ausstellung/der-montierte-mensch.

[ii] Letters to Omer, a lyrical performance. Berlin, Gropius Bau, 14 Jan. 2024. The performance was followed by a discussion with the artist in the rooms of the presentation with Zippora Elders, the curator of her0.

Selma Selman. her0

11.11.23 – 14.01.24, Gropius Bau, Berlin

Leave a Reply