From the Dining Hall to the Budapest History Museum: Contemporary Roma art and cultural heritage, trapped in community space?

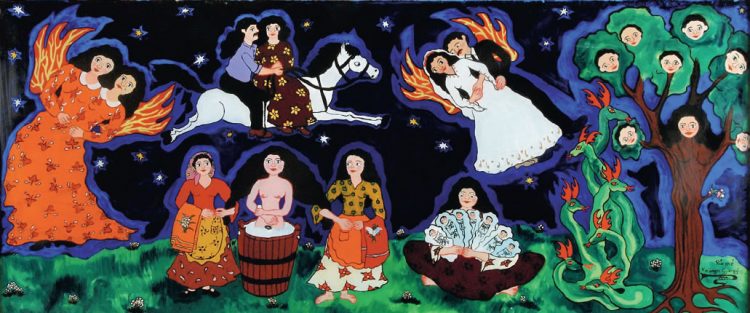

Gyöngyi Kalányos Rácz: Little Snake with Seven Twin Horns/ Hét ikerszarvas kigyócska, 1980, oil on fibreboard. Source: https://www.sulinet.hu/oroksegtar/data/magyarorszagi_nemzetisegek/romak/az_emlekezes_szines_almai/pages/aesza_09_raczne.htm

The present text[1] presents a brief overview of the cultural and communal mission of Romano Kher from Hungary, especially focusing on their summer camps where significant artworks were displayed and made a major impact on generations of Roma youth. I argue here that due to a lack of proper institutional background, Roma cultural and art heritage has been often trapped in community spaces instead of museums.

The Budapest Gypsy House Romano Kher, founded under the name Gypsy Social Centre for Education and Methodology during the last years of state socialism, functioned under the Budapest Municipal Council until 2010, when FROKK (the Budapest Roma Cultural and Educational Centre) became its successor. Romano Kher, this unique and extremely high-impact institution, was practically the continuation of the Rom Som Gypsy Club, founded in the mid-1970s at Kozák Square, in the 15th district of Budapest. The legendary cradle of Hungarian Roma culture, gathering the central personalities of the first generation Roma intelligentsia and art world (including Tamás Péli, József Choli Daróczi, János Balogh and Jenő Zsigó), emerged as a weekly club for Roma youngsters, but after the democratic turn in 1989 evolved into a complex and multifunctional organisation.[2] The Romano Kher – under the direction of Jenő Zsigó – operated between 1987 and 2010, in part still in the 15th district, but also, due to their scholarship programme and through their extremely varied cultural activities, in several Roma and non-Roma cultural institutions of Budapest. Among others, in the Roma Parliament that was on Tavaszmező Street in the 8th district, at the Thalia Theatre where they organised the annual concert of scholarship-holders, and last but not least, at the lakeside summer camps in Balatonszemes.

Although there has not yet been sufficient research on the entire oeuvre of Romano Kher, a number of texts have highlighted its importance in the recent history of the Hungarian Roma. Ernő Kállai, for example, emphasised the very wide range of activities, enumerating the involvement of several thousand campers (from primary school pupils to pensioners), and the financial support of young Roma scholarship-holders (studying in secondary and higher education). Kállai also underscored that the majority of still active contemporary Roma artists “grew up” in the art camps in Balatonszemes, and that it was the Romano Kher who organised most of their individual and group exhibitions.[3] Furthermore, Mária Neményi and Júlia Szalai, in their text about the history of recent Roma politics, highlighted the identity- and community-building power of the Balatonszemes camps. They stressed the fact that the political socialisation of young people of diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds (Vlach, Boyash or Romungro, coming from a wide range of rural or urban areas) often started there, in the summer camps. During the early years, still within the framework of the state-socialist regime, and later, in the emerging democratic system, the campers as well as the camp counsellors (social workers, politicians, artists), set a personal example of “formulating their opinions and criticisms as self-conscious Roma”.[4]

In the dining hall of the summer camp, a huge painting was displayed: Gyöngyi Kalányos Rácz’s Little Snake with Seven Twin Horns, which was originally a scene from an animation movie. The children, youngsters and adults in the summer camp had been eating, dancing, and having discussions – passing the majority of their community life – in front of this painting for long years. Kalányos, a self-taught artist, had assisted in the making of the animation film still as a child, after meeting director Ágnes Pásztor from the Pannónia Film Studio in Pécs. While the film was in competition at the Cannes Film Festival in 1986, this success was not shared with Gyöngyi Kalányos Rácz, and due to her disappointment with the only symbolic (or even humiliating) tokens of appreciation, she would not paint again for years. In the 1990s, she started to work again, subsequently becoming an honoured member of the art camps in Balatonszemes and of Romano Kher itself, publishing art albums[5] and organising exhibitions.

In 2001, the Budapest City Council took over and privatised the holiday camp in Balatonszemes.[6] Consequently, during recent years, the Romano Kher organised its summer camps in various other places and from 2006, in Fonyód at Lake Balaton. However, in 2003, the summer camp did not take place at the lakeside, but in the Andrássy Castle in Tiszadob, which, since 1949, was the home of one of the first and largest public orphanages in Hungary. Although neither the children of the orphanage, nor the summer campers stayed in the castle itself (built between 1880 and 1885 in neo-Gothic and Romantic style), but in the slightly broken-down annexes, where the castle garden and the bank of the Tisza River created a unique atmosphere. Since 1983, the dining room and community space of the castle’s former salon concealed a special treasure: this is where Hungarian-Roma painter Tamás Péli, after graduating from the Royal Academy of Visual Arts in Amsterdam, painted his Birth panel painting. The 43 m2 painting depicts the ethno-genesis and original myth of the Roma people, the birth of the first-born child, Manush, offered by the goddess Kali, scenes and figures from the intertwining Roma and Hungarian history, the central personalities of the emerging Roma cultural movement from the 1970s, and much more. The art historical analysis of this panel painting should be the topic of further articles and scholarly writings.

What should be emphasised here, however, is that Péli – creating the panel as commissioned by the Szabolcs-Szatmár Bereg County Council – painted this work primarily for the Roma children of the orphanage, who had been deprived of their Roma identity and cultural roots. Secondly, it was made as a duty for all of society – both majority and minorities – who are responsible together for recognising and accepting Roma culture, history, and its people, and for integrating them into the European historical and cultural canons. As Péli stated, in his characteristically poetic words: “The world, into which an artwork is placed, should cherish and caress it, should take care of it, talk with it and about it. This painting, this child should be enrolled into university. When we separated, I thought that I was giving it to educators – I think of society here – who were taking care of it. That small community, who owns this painting, really matured into this role. I am talking about the City of Children in Tiszadob. There lies a capacity for this: they are guarding and loving it; they know what it means and what it is speaking about”.[7]

According to Aranka Áncsán Illés, who managed the orphanage for decades, Birth perfectly fulfilled the role that Péli dedicated to it: the children in Tiszadob took care of it, admired it and presented it to visitors, with a gradually developing knowledge about it. Furthermore, they organised Gypsy clubs, and discussions about Roma culture and history in the space framed by the panel painting. Well-known Roma personalities and artists, including József Hontalan Kovács, István Szentandrássy, and József Choli Daróczi, among others, who are actually depicted in the painting, regularly visited Tiszadob. Besides talking about their own work, they also spoke about their friendship with Péli and about the communal, almost mythological painting of the panels. Péli finished the painting of Birth in Tiszadob, together with his above-mentioned friends and family, over a period of several days, complete with role-playing games, parties and camping in front of the panels.

A few years after the Romano Kher summer camp took place in Tiszadob, the orphanage was structurally modified and moved from Tiszadob, while the Andrássy Castle – following years of renovation – in 2016 became a representative event venue within the framework of the National Castles and Forts Programme. However, already in 2011, the state authorities had removed the Birth panels from the wall of the dining hall, so that during the last ten years, it was in storage in a corridor of the Jósa András Museum in Nyíregyháza (eastern Hungary). That it did not fall into total oblivion is largely due to the documentary film, entitled Late Birth, from 2002, shot by Edit Kőszegi and Péter Szuhay, which, apropos of a trip to Tiszadob, introduced the Roma intelligentsia and cultural history of the 1970s and 1980s with a special sensibility. This film is a significant document of memory, due not only to the characters introduced, among whom so many have departed since then: Tivadar Fátyol, Menyhért Lakatos, and József Hontalan Kovács. It was also so important because of making the Birth panel painting visible; for the last ten years, a rather poor-quality photo, taken during the shooting of the film, was the only record of the painting that one could find on the internet.

Tamás Péli: Születés / Birth, 1983, oil on fibreboard panel painting in four pieces, total: 460cm x 910cm. Installed at the Budapest Historical Museum (BTM) for OFF-Biennale 2021. Photo: ERIAC.

In June 2021, Birth became visible again, even if only for a few months, in the Baroque Hall of the Budapest History Museum. The exhibition, entitled Collectively Carried Out: Tamás Péli’s Birth[8], in the framework of the Off-Biennale Budapest, and the RomaMoMA project of ERIAC Berlin, presented the painting within the magnificent installation of intermedia artist Tamás Kaszás. He transferred the gigantic panel to an untreated wood stage (equal to the size of the painting), upon which the four panels of the artwork were not directly attached to each other, but were left with a narrow gap between them. On the one hand, the gaps referred to the fragile, tormented status of the panels, as well as of the entirety of Hungarian Roma art heritage, which was never able to completely realise its purpose. On the other hand, they also pointed to future uncertainties: the incomplete nature of the painting’s destiny. The stage recalled the space of the former dining hall in Tiszadob, also creating opportunities for discussions and collateral events during the term of the exhibition, in the immediate proximity of the painting. The exhibition concluded at the end of September, and the painting was put into storage, yet again. Until its future destiny and final placement is found, it will again remain invisible, similarly to Little Snake with Seven Twin Horns, as well as other pieces of the Romano Kher’s art collection.

Literary historian and journalist János Róbert Orsós, in his article[9] from July 2021, in relation to the Péli exhibition and the temporary gallery of the Roma Parliament[10], wrote about the liberation of Roma fine arts. It could be understood, however, that the veritably significant life of the provisionally liberated Roma artworks has taken place thus far in community – and not museum – spaces. Without a proper institutional background – and instead of enumerating all of the broken promises about the foundation of a Hungarian Roma museum, it is much more worthwhile to read the statements published by ERIAC[11] and the Off-Biennale’s RomaMoMA project[12] itself – numerous Roma artworks (of many hundred square metres) have made a major impact on the walls of dining halls in holiday camps and orphanages. Although they have been mostly kept out of sight from the majority society’s gaze, for several generations of the Roma academic, cultural and artistic scene, they have offered a primordial frame of reference, and at the same time, a serious and legendary cultural foundation, whose impact may be even more significant than the aesthetic value of the paintings. The (physical or imaginary) stages constructed before them have created strong political, community-building and self-representational fields of force, where the Roma children of the summer camps or the orphanage could feel more powerful and proud. In our contemporary society, where racism and discrimination continue and accumulate, this could be an exemplary value.

Eszter György

[1] The present text is an adapted translation of the Hungarian text, “Tábori eblédlőből a Vármúzeumba: Hol a helye a kortárs Roma képzőművészetnek?” [From the lunchroom to the Castle Museum: Where is the place for contemporary Roma art?], in Qubit, 19.09.21, see: https://qubit.hu/2021/09/19/tabori-ebedlobol-a-varmuzeumba-hol-a-helye-a-kortars-roma-kepzomuveszetnek

[2] György, Eszter (2019): “An attempt to create minority heritage: The history of the Rom Som Club (Rom Som cigányklub) (1972–1980)”, in: Romani Studies 5, Vol. 29, No. 2, 209–36 [specifically 220].

[3] Kállai, Ernő (2000): “A cigányság története 1945-től napjainkig” [The History of the Gypsies from 1945 up to the Present Day]. In: Kemény, István (ed.): A magyarországi romák [The Roma in Hungary], Budapest: Útmutató Kiadó, 16-24. See: http://www.kallaierno.hu/data/files/1945_tol_kiskonyv_+XGKix.pdf

[4] Neményi Mária, and Szalai Júlia (2019): “Elbeszélt évtizedek: a roma politika közelmúltbeli története roma politikusok szemével” [Recounted Decades: The Recent History of Roma Politics Through the Eyes of Roma Politicians], in Neményi Mária, Szalai Júlia, Kóczé Angéla (eds.): Egymás szemébe nézve. Az elmúlt fél évszázad roma politikai törekvései [Looking Into Each Other’s Eyes: Roma Political Aspirations of the Past Fifty Years], Budapest: Balassi Kiadó, 17-83 [specifically 47-48].

[5] For instance, Zsigó Jenő (2009): Cigány festészet – Magyarország 1969-2009: Válogatás a Fővárosi Cigány Ház – Romano Kher közgyűjteményéből [Gypsy Painting – Hungary 1969-2009: Selection from the Public Collection of the Municipal Gypsy House – Romano Kher], Budapest: Fővárosi Önkormányzat Cigány Ház [Municipal Government Gypsy House]. See: https://www.regikonyvek.hu/kiadas/cigany-festeszet-magyarorszag-1969-2009-2009-fovarosi-onkormanyzat-cigany-haz

[6] See articles: A Parlament előtt tüntetett a Romano Kher (origo.hu)

such as: https://www.origo.hu/itthon/20010309aparlament.html,

in English translation: https://www-origo-hu.translate.goog/itthon/20010309aparlament.html?_x_tr_sl=hu&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc

[7] Kovács, József: “Egzotikus vadállatok voltunk. Beszélgetés Péli Tamás festőművésszel” [We were exotic wild animals: Interview with painter Tamás Péli], in: Kritika, 1990, 31.

[8] See: https://www.varmuzeum.hu/kozosen-kihordani.html

[9] Orsós, János Róbert: “Felszabadított roma képzőművészet – legalábbis szeptemberig” [Liberated Roma Art – until September, at least], in: artportal, 16.07.21. See: https://artportal.hu/magazin/felszabaditott-roma-kepzomuveszet-legalabbis-szeptemberig/

[10] In April 2021, the local municipality of the 8th district in Budapest offered a temporary gallery space to the former collection of the Roma Parliament, closed in 2016. See: Roma Polgárjogi Mozgalom – MRPE [Roma Civil Rights Movement], https://romaparlament.hu/kepzomuveszeti-gyujtemeny/

[11] For instance, Tímea Junghaus: “Argument for a Roma Transnational Museum”, on this RomaMoMA blog. See: https://eriac.org/argument-for-a-roma-transnational-museum/

[12] See: https://offbiennale.hu/en/2021/projects/romamoma

Leave a Reply