Yesterday Can Tell Us a Lot About Tomorrow

Delaine le Bas: Jivipen Ta Divvus | Life Today | Living for Today, performance, BWA Tarnów, 2014. Photo: Jola Więcław.

The 2014 exhibition, Tajsa, which I curated together with Katarzyna Roj, presented me with a great challenge. Up to that point, I had been putting on humble independent shows in places that did not have the status of a public institution. In my world, everything happened in real time: there was no long-term project schedule, no promotional plan. Production capacity would always depend on material resources and opportunities for barter, not on a real budget. The Tajsa exhibition, in contrast, was developed as part of the project, Out of Sight, Out of Mind: Cycle of Exhibitions of International Contemporary Artists Embracing the Heritage of Małopolska, and was held at the BWA Gallery in Tarnów. My method of working, in the here and now, resonated somehow with the whole project and its subject. The subject of our non-object-based exhibition was the experience of Roma communities, and the attempt at linking selected issues to strategies for living today and tomorrow.

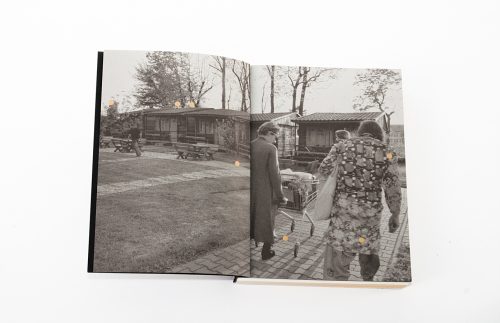

Tajsa catalogue, eds. Katarzyna Roj, Joanna Synowiec, BWA Tarnów, 2014.

Tajsa is a word in the Romani language, which in several of its dialects means both yesterday and tomorrow, depending on the context of the sentence, as pointed out by Krzysztof Gil – a Polish-Roma artist whose doctoral thesis was entitled, Tajsa: Yesterday and Tomorrow – in his essay opening our non-object-based exhibition. It also perfectly captures the experiences and existence of some European Roma (e.g., from Romania or Bulgaria), who are often migrants of late. For a number of these groups, the present is the only real tense. With no yesterday and no perspectives for tomorrow, there is only today. The strategy for today often consists of provisional actions, using available, recycled materials. Is this relevant solely to the experience of the Roma, though? The permanent state of transience in the age of capitalism has been the universal experience shared by a large part of humanity. We are being driven to desire what we cannot afford. Eschewing these aspirations may not only save us from indebtedness, but also be a form of resistance against the neoliberal system of values, in which ‘permanence’ and ‘continuity’ are mere phantasms that always have to be accompanied by the purchase of goods. The major theme of the Tajsa project was thus reflection on the present.[1]

The subject stemmed from a number of factors: on the one hand, from the experience of the Nomada Association that I am affiliated with, and which supports the Romanian Roma who for many years lived on abandoned allotment gardens in Wrocław. They stayed in houses they had built themselves using acquired, available materials. They had left Romania to look for a better place for themselves and their families. They made me confront many experiences of the Roma and of humanity in general. Exclusion, poverty, precariousness, but also community, resistance and standing up for oneself. A strong patriarchal system, but also extremely creative emancipation of women. This is my foundation for this project. I approached the exhibition about the Roma experience from a socially engaged perspective. On the other hand, Katarzyna Roj, as a curator of the public institution BWA Design Gallery in Wrocław, who deals with the broadly understood subject of design, saw great potential in the issue of the Roma experience as one that can relate to the future of design in the post-productive world. With overproduction and overconsumption already being widely discussed today, we could look to strategies of living and functioning of social groups and communities that are able to manage minimal resources in a maximal way. What became the most important aspect for us was exchange. Exchange is understood as flow, understanding, conversation and collecting experiences, which would then translate into creative interpretations or become art in their own right. The foundation was to consist of scraps, fragments from the life of the Roma communities, such as an apron made by Delaine Le Bas during her performance, based on a photograph from Jerzy Ficowski’s book, The Gypsies in Poland: History and Customs. Delaine’s performance was itself a presentation of topics without explicit answers, or rather a series of open-ended questions about the foundations of emancipation, equality, and the nomadic subject. Her artistic approach clearly demonstrates that bringing all this to the table provides an opportunity for a revision of history, and a change or expansion of the field of history to include the subjective voice of minority groups.

Engaging with the Roma experience in the field of art, we did not form a theory or a model of a contemporary traveller or wanderer. We did not attempt to create a coherent narrative on the subject of the Roma identity; we were far from defining individual Roma groups. We sought a space where many individual stories could resonate.

We were interested in what has emerged from the experience of transitoriness resulting from the necessity to relocate, faced by some Roma and Traveller groups. In the book, Nomadic Subjects, Rosi Braidotti claims that nomadism is a theoretical alternative and existential situation that translates into a mode of thinking in general. The nomadic consciousness itself constitutes an epistemological and political imperative of critical thinking. In this way, mobility has come to embody a broader context than just the capacity to move.

We followed the words of Tímea Junghaus, curator of Paradise Lost, the first Roma Pavilion at the 52nd Venice Biennale in 2007. We considered the Roma identity to be also the identity of the contemporary migrant – one who is open to fusion, out of necessity or conviction, seeking opportunities to fulfil their needs, adapting to a new space and place. The exhibition did not present artworks in a traditional sense, artistic objects, but instead created conditions for activities of an artistic and cognitive character to take place. Specially arranged scenography provided the setting for performative actions, lectures, film screenings, and workshops for children and adults. A significant aspect of these activities comprised collaboration with the Tarnów Regional Museum, which deals with Roma subject matter and showcases the history of the Roma through its collections.

Special Cases

Micro-residencies were also a part of the project, during which the invited artists produced their works. Marian Misiak made a neon sign of Tajsa, in an attempt to design the lettering for the Romani language. In his process, he conducted interviews with representatives of the Tarnów-based Roma community, and with the researcher and ethnologist Adam Bartosz. Misiak emphasised that he had received contradictory information from the researchers and the community representatives. In his essay written for the Tajsa catalogue, entitled Magic Language, Damian Le Bas described the phenomenon of seeking to prevent the dissemination of one’s language, thereby assigning magical qualities to it. He continued to say that the most magical thing about the Romani language is that it is still alive within numerous dispersed communities, with no state, no structured school education, that it is alive and influences the representation of reality, while also being subject to influence. It holds a space of soft relational character and a solid foundation.

Paweł Kulczyński created his work, Protest Song, based on the material selected by Paweł Szroniak – a legal act dating back to the period of the People’s Poland, which outlawed the Roma community’s nomadic lifestyle and forced them to settle. The text was recited, translated into Romani and commented upon by Marzena Siwak – an incredibly charismatic Roma resident of Tarnów – during workshops run by Katarzyna and Zbigniew Szumski. We presented the piece in the public space of a park, in a somewhat hip-hop-like repetitive rhythm. For a few moments, voice took over the space.

While trying to come up with an idea for her artwork, Karolina Freino decided to consult a Roma fortune-teller. This was her way of entering the unknown. During the visit, she rather unexpectedly found a sign that guided her in the right direction – a Śpera.[2] She made a Śpera from a rootless plant called tillandsia.[3] It was then attached to a black locust tree in the park surrounding the BWA Gallery, and constituted a slightly exotic, albeit almost invisible, sign, beautifully growing into the structure of the tree.

Krzysztof Gil made live charcoal drawings on paper during a meeting with Monika Weychert, the curator of the exhibition, Houses as Silver as Tents, who gave a talk on why a Romani exhibition was a trap. He also documented the finale of the project – a performance, The Feast, by Monika Konieczna and Ewelina Ciszewska. Gil observed the events and drew them on paper, thus making his intimate art, as he declared in his essay opening the series of events.

What One Could Not See

The entire initiative was documented in the exhibition catalogue. As editors, we strived to capture the spirit of those meetings and the themes of the talks, speeches, and workshops. Many of the activities were not visible, but could be experienced through participation.

Krzysztof Gil: drawing the performance, The Feast, BWA Tarnów, 2014. Photo: Jola Więcław.

I open this publication today and find myself enjoying its diversity, and the energy I remember coming from the project itself. A melting pot of voices, different perspectives, polemics, interviews offering personal perspectives, and speeches delivered during the events. Yet, even all of this is not enough: it remains just a snippet of important accounts – I still feel hungry for more people, stories, and artworks.

The Song of the Future Does Not Make a Happy Sound

A year after the show, thousands of refugees were making their way to Europe from countries at war, such as Syria, or where repression of citizens is a permanent state of affairs, such as Iran. Temporary refugee camps on the borders of European countries in a way became a representation of changes in the world, as well as the apotheosis of non-negotiable compliance with the conditions and opportunities. What we could see here were people forced into exile by war and authority, looking for a new place to lead a peaceful life. They did not know how long it would take, where their journey would end, what physical toll it would take, or how they would keep their children from worrying.

Monika Konieczna, Ewelina Ciszewska: The Feast, performance, BWA Tarnów, 2014. Photo: Justyna Fedec.

They learned everything along the way. They laughed at little things, and suffered because of big ones. They were in fear, freezing, but holding out hope until there was no strength left. In political terms, they became refugees; one day they woke up, got dressed, took what was most important, or most necessary, and left home, which they do not always hope to return to. Nomadic subjects – that is what Rosi Braidotti might call them. I was a volunteer on the Croatian-Hungarian border for a week, maybe longer. Every day, I would see thousands of people who had to flee their world, whose aim was to find a refuge, not necessarily attaching a country’s name to the place. They realised that they might be in for a long journey. The borders of Europe closed to them rather quickly. Our questionable hospitality, ever so conditional in Kantian terms, did not let this phenomenon be seen in the wider sphere of social solidarity.

This is, among other things, the result of a policy of ignoring minority communities and their stories, which are often incredibly formative, significant and relevant to the present day; shelved as folklore, they cannot resonate in a broad political sense. Joanna Kwiatkowska-Talewicz, who also participated in the Tajsa project, said in one of her interviews that while Romania had joined the European Union, the official policy of the country was racist towards the Roma minority, excluding them structurally and politically.

At the beginning of her lecture, Tímea Junghaus recalled the situation in 2008, when Hungarian paramilitary forces entered a town in order to frighten the Roma inhabitants, and in so doing triggered a wave of violence against them.

In creating the non-object-based exhibition, we speculated about the future and developments, hoping that we were heading towards a broadening of the perception of micro-histories and personal narratives. Yet, what we currently face is a backlash from a strong, amplified, conservative voice of power that has no intention of working through the experiences of minority communities, and instead reproduces violence in interpersonal relations, mainly in structural terms. Failing to confront Roma history leaves us unable to see the wider context of the current state of abuse, as well as all that lies ahead.

Reading the words of Virginia Woolf: “As a woman I have no country. As a woman I want no country. As a woman, my country is the whole world”, I think that to understand their meaning one has to know the context and the world in which they were spoken. In the first half of the 20th century, in most places in the world, women had no civil rights, were not allowed to vote, or to manage their own material resources, and it was the men of their families who decided their fate. Every form of emancipation comes with a struggle, with exclusion – a high price to pay as far as family and social relations are concerned. The concept of internationalism is so tempting: to be free from national oppression, to have the entire world as your home. And yet, when this formula is applied to specific cases at specific times, it can seem like a nightmare. Still, the knowledge of the history of exclusion, of no sense of belonging, of escape, or of being on the road due to an unregulated situation or insecurity is essential to get insight into the future and to avoid this scenario.

It is impossible to universalise what various Roma groups have experienced, but recounting their stories allows us to explore the practices of resistance employed by communities that have been enslaved, oppressed and marginalised for centuries.

Krzysztof Gil: live charcoal drawings, The Feast, BWA Tarnów, 2014.

These days, the fields of history, anthropology and art in Poland are opening up to talk about the social class of peasants, who remained slaves until the abolition of feudal property. In conservative circles, this turn towards the human face of the peasantry triggers great resistance – an attempt to prevent a potential rewriting of the pages of history. Shifting the spotlight to absent, marginalised and untold stories offers a chance to see the bigger picture of historical events and their significance for the narrative of one’s own identity, roots and traumas. Classical history does not make room for vulnerability, or for voices of ignored communities, such as the Roma, peasants, and women; however, working with the history of essentially large parts of different social groups gives hope for change in the future. The significance of exposing further exclusions leads us to believe that they may not happen again.

Krzysztof Gil: live charcoal drawings, The Feast, BWA Tarnów, 2014.

In Poland, we fail this test, both with regard to the history of the experience of those Roma groups who have been Polish for generations and live in different parts of the country, and those who have come here from Romania. We fail the test as regards the situation of women, the LGBT+ community and, especially recently, refugees who, like hostages of big politics, remain stranded on the Belarusian-Polish border, repeatedly forced behind our wall of prejudice and lack of understanding. Today, they are the embodiment of the situation that we have not yet worked through in the broader context of the history of such communities as the Roma.

If we had accomplished this, by studying the dependencies, and the hierarchy of power, by understanding the resistance and the struggle that has continued for generations, we would have a better chance to open the borders of our perception to the situation of the Afghan or Iraqi refugees.

Without the history of the Roma, we cannot experience wholeness, just as without the history of peasant slavery, we will not recognise the traumas that remain within us, but which we cannot access. Without being whole, we do not feel a sense of agency and integrity, and it is integrity that gives us space for subjective relations with others.

Joanna Synowiec

[…] Previous Blog Entry […]