Disrupting the Institution through Language and Enactment: Omara’s Resistance, Part II

“Here are Omara’s provocative breasts”[Na-itt-van-az-Omara-provokatív-mellei], Ball point pen on photo 15×21 cm. Courtesy of Everybody Needs Art and Longtermhandstand, Budapest

Though she only began to make art at the age of forty-three, Omara (Mara Oláh, 1945–2020) became one of the most prolific Roma artists of her generation. Born in Monor, Hungary, to a musician father and a mother from a tinker family, Omara juggled multiple jobs, working primarily as a cleaning lady, until one day, she asked her daughter to bring her a piece of paper and a pencil, while she was suffering from a migraine. She drew a portrait of actress Sophia Loren, and by the time it was completed her pain had dissolved (Medgyesi 2011, 24). Realizing the healing potential of making art, she began to paint episodes from her life, including childhood memories, traumas, and reflections on motherhood. As a Romani woman and cancer survivor, her first-hand experiences of dispossession, sexism, anti-Gypsyism, police violence, and neglect in the healthcare and education system provided the subjects of her paintings. While Part I, featured on MoMA’s post platform, highlighted the artistic activity of a pioneer who introduced Roma resistance into the institutions of art, this paper focuses on how her personality—or rather, artistic persona—shaped her video performances, media and public appearances, based on existing documentation and interviews with her former colleagues and friends.

Omara began her artistic career as a ‘naive gypsy painter,’ as she liked to call herself, and participated in exhibitions showcasing the work of Roma amateurs in community centres and marginal art institutions. Her works were first presented in a contemporary art setting in 2004, at Hidden Holocaust, the exhibition of Műcsarnok, Budapest. Since then, Omara has gained international recognition for her unique narrative paintings; her works have been shown across Europe and the United States, including at the Roma Pavilion of the 52nd International Art Exhibition of Venice in 2007, and most recently at documenta fifteen, at a show presented by OFF-Biennale Budapest and the European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture (ERIAC). While Omara’s paintings have been widely exhibited, it was only in 2011, through the writings of curator and art historian Tímea Junghaus, that her ‘actions, media presence, and performances’ (Junghaus 2011) became the subject of analysis. In her seminal essay, ‘Epistemic Disobedience: A Decolonial Reading of Omara’s Blue Series,’ Junghaus positioned Omara’s body of work in the framework of feminist and decolonial theory, and highlighted the importance of her ‘artistic actions, hysteria, scandals, protests, and political statements communicated through printed or online platforms in the media’ (Junghaus 2013, 310).

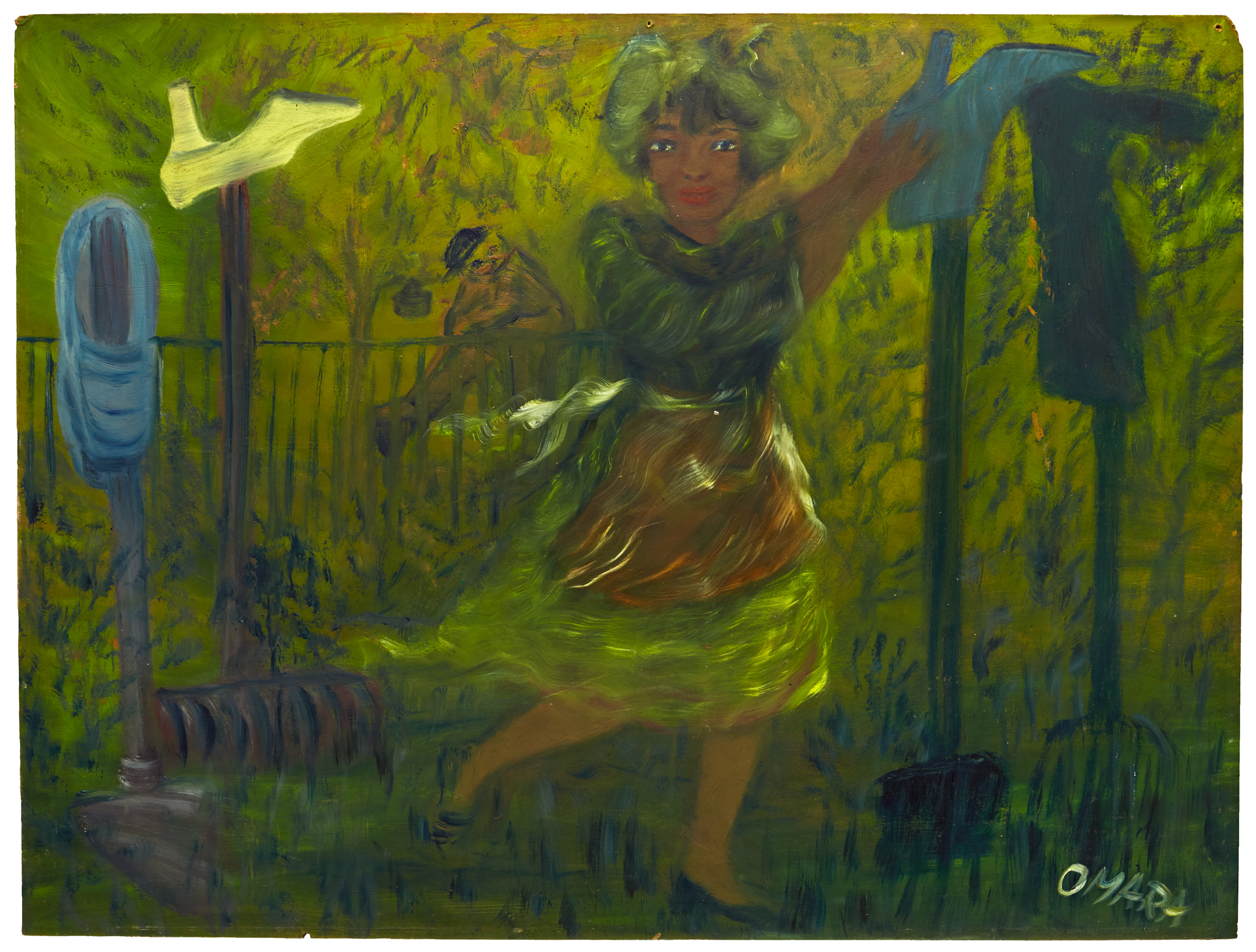

Omara:“But I dont scrape” [márpedig én nem kapálok], 1990-1992. Oil on fibreboard, 57×76 cm. Courtesy Everybody Needs Art, Longtermhandstand

Self-representation as an ‘extreme personality’

‘One night I dreamt they were visiting me from the TV, and I was wearing this dress during the shoot. Guess what! Without so much as a call or a message, two days later Gypsy Magazine came to film me. All right, I said, but I need fifteen minutes to put on this dress I had dreamt about […] They said this wouldn’t be allowed to air. Put on something else. To which I said: ’Did I call you here? I didn’t. […] Do you want to film me while scrubbing shit? Why didn’t you film me when I was a cleaning lady? Since you want Mara, the painter, this is what you get. Like it or not, this is the personality I now have.’ (Omara 1997, 25)

Due to her various public gestures, media appearances and scandals, professionals and the press often called Omara an ‘extreme personality’ (Földes et al. 2011). While it was undoubtedly a strategy of hers to provoke through her use of language, look and behaviour, employing her voice to disrupt the status quo was not merely an artistic gesture, but a tool of survival. ‘Now, let’s get back to shouting,’ she wrote in her self-published text, Gypsy Mothers Should Be Crowned. ‘So he shouldn’t shush me and the other gypsies, and should consider instead why God gave us a big voice. Evidently, to protect ourselves!’ (Omara 2006). As fellow artist Zsolt Vári says: ‘Omara’s expectation of herself was not to let anyone tell her how to talk or behave, and if they did, she should double down on her act’ (Vári 2022).

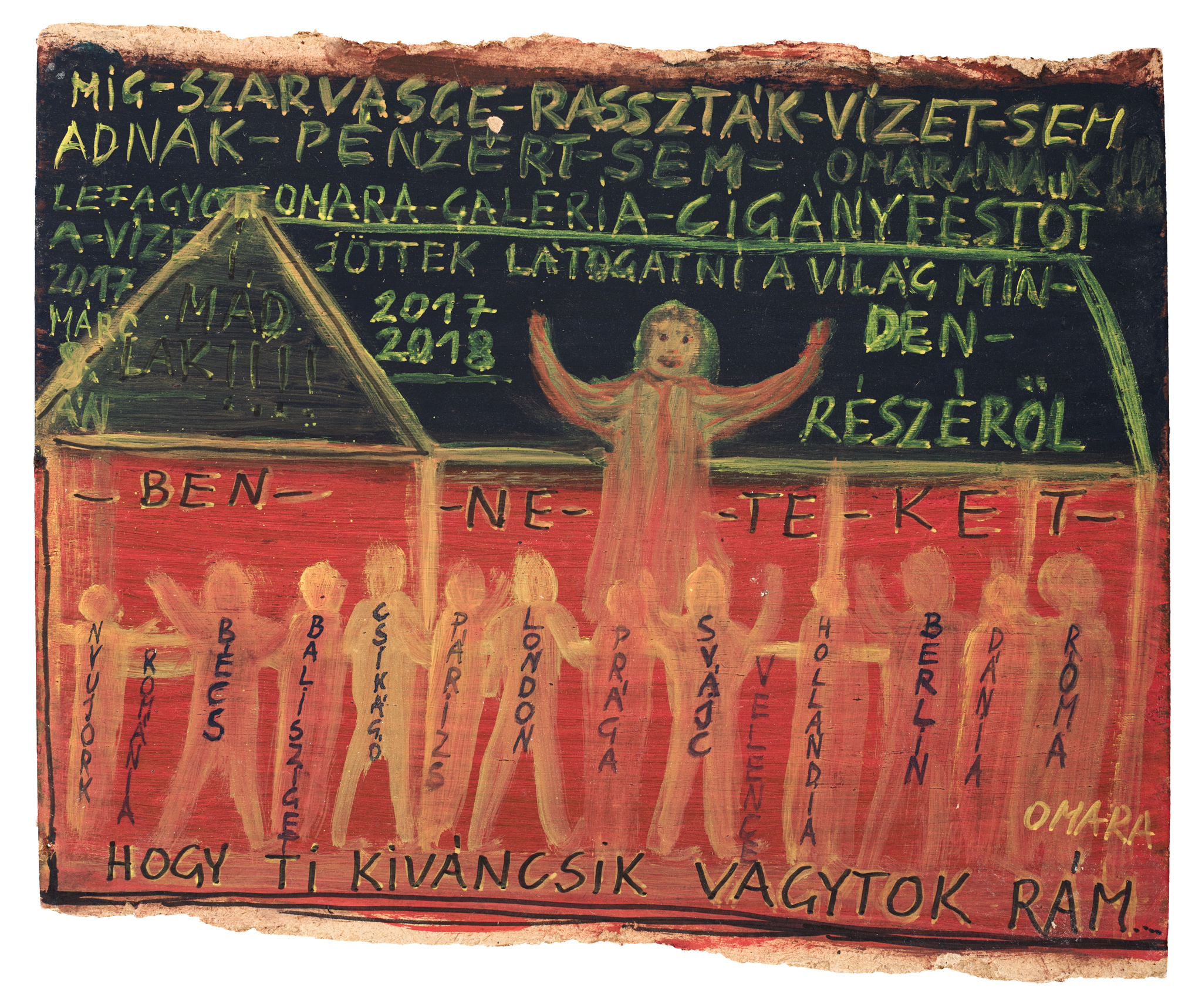

Acting on her ‘extreme personality,’ Omara set up her own rules for participating in the art world, frequently naming, subverting or calling attention to societal hierarchies. To begin with the most glaring example, she called everyone a ‘diamond’ [‘gyémántocskám’] or ‘golden weenie’ [‘arany tököcském’], from fellow artists to the President of Hungary. She was also consistent about her preferences as an artist: whenever she was invited to an exhibition, Omara requested a white Mercedes and asked for a driver who smoked and had a moustache (Pócsik 2022). Once, when attending a reception by the Open Society Foundation, the artist requested the organizers to provide a drink for her driver, and when they refused to do so, she stormed out of the function (Vári 2022). Towards the end of her career, Omara even established her own exhibition policies: to prevent theft of her works, she only consented to a display of her paintings ‘if they had been purchased, insured to a million euros, or if she was allowed to live in the exhibition space,’ said gallerist and curator Peter Bencze (Everybody Needs Art/Longtermhandstand), who represents the artist’s estate (Bencze 2022). Later in life, she built a house in Szarvasgede, which she referred to as her ‘luxury hut’ and which anyone intent on exhibiting her work was expected to visit, as if on a pilgrimage. One of her paintings depicts all those who visited her from New York, Paris, Berlin, and other art capitals around the world, with an inscription complaining about the racist residents of her village.

OMARA-Mara-Olah: “While the Racists in Szarvasgede…” [“Míg szarvasge[dén]… rassz[is]ták…”], 2017–2018, Oil on fiberboard , Courtesy of Everybody Needs Art and Longtermhandstand, Budapest

“While the racists in Szarvasgede won’t even give water, even for money, to Omara!!! – My water [pipe] has frozen. – Omara, the Gypsy painter receives visits from all over the world: New York, Romania, Vienna, Bali, Chicago, Paris, London, Prague, Switzerland, Venice, The Netherlands, Denmark, Roma. – I love you all!!!! for being curious about me…”

Performance or enactment

Acts of defiance were part of Omara’s artistic practice from the beginning of her career.(1) However, the first public action theorized to be part of her artistic output became her handing over her glass eye to billionaire George Soros at the opening of the Roma Pavilion in Venice in 2006, as a gesture of gratitude (Junghaus 2011). Omara never titled or framed her media and public appearances, interventions or video performances as works of art, yet they constitute an essential part of her artistic practice and have to be reckoned with in order to fully understand her significance as a trailblazer, who was not afraid to voice her opinion and challenge notions of normativity and inclusivity in the art scene, as well as in society.

Omara’s public actions could be called performances, performative gestures or action art, (2) yet there is no consensus on how to describe these occasion-specific works, which rely on the artist’s presence and provocative statements. It feels appropriate to call them enactments, following Andrea Fraser, who proposes to use the term instead of ‘performative actions,’ as the latter has been appropriated and (mis)used by the art discourse to the point of being emptied of its original meaning: they are ‘utterances that DO things’ (Fraser 2014, 123). In Omara’s case, it is evident that her gestures and statements are not exclusively framed by or tied to an art discourse, and its consequences are felt in a larger context: she succeeds in bringing her minority voice into the limelight (from exhibition openings to TV appearances) and assumes an active role in shaping the perception and treatment offered to her, as well as to others in her position. Enactment can also refer to something Omara liked to do at exhibition openings and guided tours, that is, reading out the inscriptions of her narrative paintings, adding comments and explanations.

Sugár János: Omara (2010), 2010, video, 29 minutes, excerpt.

‘Omara cannot be directed’: controlling the narrative

Since Omara never named, recorded, or framed her actions as works of art, many live on in the form of anecdotes, in oral history, and videos. János Sugár, a long-time friend and collaborator, once recorded Omara during what curator and cultural researcher Andrea Pócsik has called a ‘personalized performance’ (Pócsik 2014). In this video, Omara (2010), she shows Sugár the paintings after they had been dismounted at her exhibition in Hotel Omnibusz in Budapest, reading out the inscriptions, adding comments and jokes, enacting the narratives they depict. Towards the end of the video, she takes out the pieces of a painting she cut up because the commissioner refused to buy it on the grounds it was pornographic—according to the artist, the picture depicts ‘pensioner whores’ who refused to help her when she approached them. She even makes a comic but unsuccessful attempt to reconstruct the work from the pieces for the camera. The recording became known as a video performance and has since been the most frequently analysed and exhibited work apart from her paintings. Most significantly, Pócsik notes, Omara took complete control of the action and presented her works and personality in the way she wanted to be seen, subverting the hierarchical relationship a camera tends to impose on those on its two sides (Pócsik 2014). Sugár himself said Omara could not be directed, and there are countless anecdotes in which Omara dictated the schedule and agenda for the film crews that attempted to work with her (Romakép Műhely 2014).

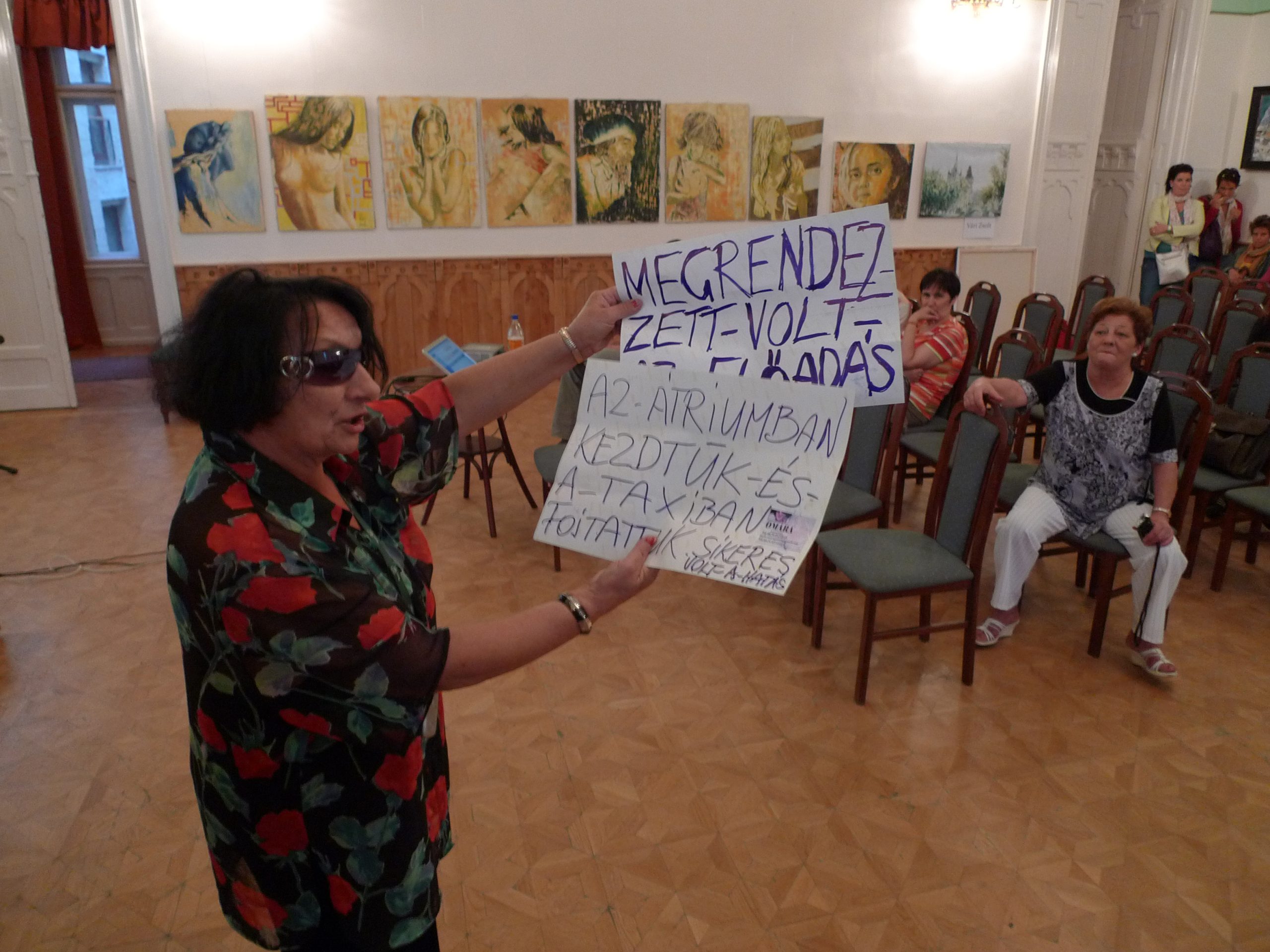

Omara at an exhibition opening at the Erzsébetváros community centre on September 8, 2009. Photo and courtesy János Sugár.

At the beginning of Sugár’s video, Omara can be heard complaining that after The Hidden Holocaust exhibition at Műcsarnok, people started to ask her ‘who she had slept with’ to be showcased in the prominent atrium space of the gallery. Then she mentioned a live intervention, which I could reconstruct thanks to Sugár and Zsolt Vári, with whom she collaborated on the action. On their way to an opening at the Erzsébetváros community centre in 2009, Omara and Vári choreographed and rehearsed a dialogue they went on to perform in front of the visitors of the exhibition. In accordance with his role, Vári called Omara his ‘whore.’ Omara even created signs that read: ’We started in the atrium and continued in the cab. The effect was successful.’ By creating a scandal—so called by Omara before it even took place (3)—the artist enacted a parody, turning the defamation on its head and placing herself in an active position where she could control the narrative. This intervention followed a similar logic to Omara’s ‘I was not invited’ scenes, in which, after she made her theatrical entry to an exhibition, round-table discussion or other event, she reproached the organizers for failing to invite her—whether or not that was actually the case (Junghaus 2011).

“Here are Omara’s provocative breasts”[Na-itt-van-az-Omara-provokatív-mellei]Ball point pen on photo 15×21 cm. Courtesy of Everybody Needs Art and Longtermhandstand, Budapest

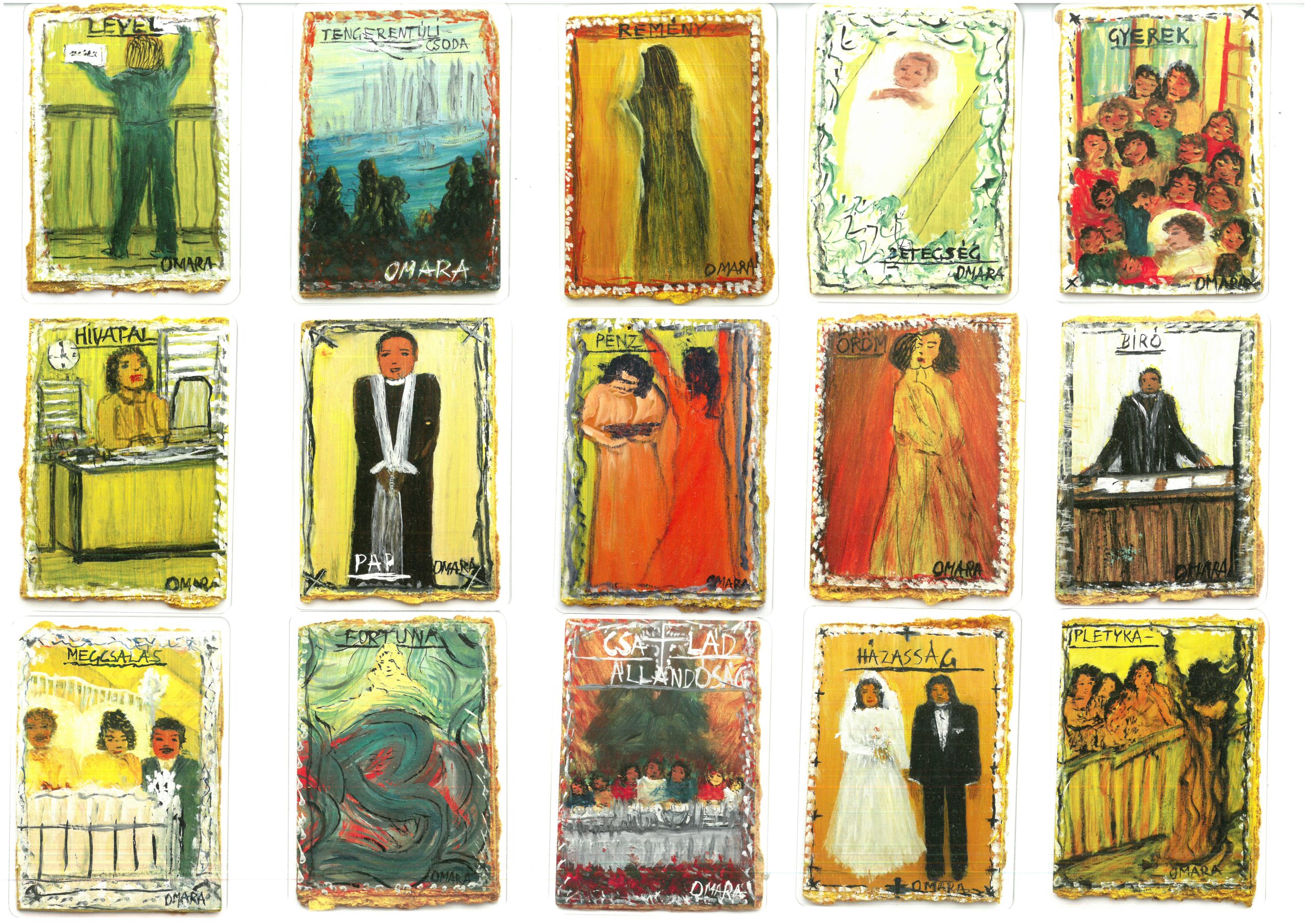

Occasionally, Omara also performed for wider audiences as a p. sychic on television. In between reading the cards or interpreting dreams, she shared stories about her personal life, her luxury hut, or her wish to find a ninety-year-old millionaire for a husband. Not only did she support herself financially with these gigs, she also made fortune-telling part of her artistic practice: Omara painted a tarot deck and called herself the ‘baddest witch’ in an interview (Medgyesi 2011, 33). Enacting stereotypes imposed on her due to her womanhood or Roma identity, she once again took the narrative into her own hands and broadcast it on Budapest TV.

Tarot deck, 2005-2010, print, 22 cards + 2 covers, Courtesy of Everybody Needs Art and Longtermhandstand, Budapest

Tending Omara’s legacy

During her life, Omara’s exhibitions were most often complemented with live-action components, some form of enactment of either her narrative paintings or the parody of societal prejudices. Since her passing in 2020, the curatorial approach to presenting her work has shifted, with more strategic attempts to bring her voice into the exhibitions. At documenta fifteen, RomaMoMA’s curatorial team deemed it essential to show János Sugár’s video portrait of Omara, to display her ‘quasi-performances’ alongside her paintings (Székely 2022). At ! Omara Occupies the Sound Space, another pivotal exhibition, curated by Andrea Pócsik for the 2021 OFF-Biennale Budapest, (4) the entire show was organized around her voice. Among other things, it featured a sound collage, composed by György Bartók from recordings of Omara’s speeches and provocations at the openings and guided tours at Liget Gallery. There was even a staged reading of the artist’s autobiographical texts, with the participation of Roma women. The exhibition focused on capturing perhaps the most significant trait of Omara, the defiant voice that she was not afraid to use. Indeed, her bold statements will continue to ring in our ears for a long time.

References:

Bencze, Péter (2022), Telephone interview, August

Földes, András, et al. (2011), ‘Extrém egyéniség fest a luxusputriban’ [Extreme personality paints in luxury hut; video], index.hu, http://index.hu/video/2011/04/24/omara/, accessed 31 Aug. 2022

Fraser, Andrea (2014), ‘Performance or Enactment’, in Performing the Sentence: Research and Teaching in Performative Fine Arts, ed. by Carola Dertnig and Felicitas Thun-Hohenstein, Publication Series of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, 13 (Berlin: Sternberg Press)

Junghaus, Tímea (2011), ‘Az egyszemlátó Omara ékszerei’ [The jewels of one-eyed Omara], Exindex (6 November), https://exindex.hu/flex/az-egyszemlato-omara-ekszerei/, accessed 8 Nov. 2022

Junghaus, Tímea (2013), ‘Az episztemikus engedetlenség. Omara dekolonializált Kék sorozata’ [Epistemic disobedience. Omara’s decolonized Blue Series], Ars Hungarica, 39, 3: 302–17

Medgyesi, Gabriella (2011), ‘Oláh Mara’, in Színekben oldott életek: cigány festőnők a mai Magyarországon [Lives dissolved in colour: female Roma painters in contemporary Hungary], ed. by Gabriella Medgyesi and Györgyi Garancsi (Budapest: Protea Kulturális Egyesület), 16–33

Omara (1997), Mara festőművész [Mara, painter] (Szolnok: self-published)

Omara (2006), A cigány anyának korona jár! [Gypsy mothers should be crowned] (self-published)

Pócsik, Andrea (2014), ‘Visszatekintés – a lázadás sürgősségéről’ [A look back—on the urgency of revolt], Romakép Műhely, 5 February, http://romakepmuhely.blogspot.com/2014/02/visszatekintes-lazadas-surgossegerol.html, accessed 31 Aug. 2022

Pócsik, Andrea (2022), Email interview, September

Romakép Műhely (2014), ‘Romakép Műhely 2011 – Kortárs roma képzőművészet’ [Contemporary Roma art, video], YouTube (uploaded 31 July 2014), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yGUaX8a7Ito, accessed 31 Aug. 2022

Székely, Katalin (2022), Email interview, August

Vári, Zsolt (2022), Telephone interview, September

(1)For example, she began inscribing her paintings in 1992 to avoid misinterpretation by curators and art institutions after an incident at one of her exhibitions in Szeged (Junghaus 2011).

(2)Artist and long-time collaborator János Sugár refers to Omara’s public performances as action art—not to be confused with action painting—which is accurate in the sense that these were primarily one-off actions that relied heavily on the presence of the artist and the reaction of the audience, but the term feels somewhat anachronistic, as Omara’s work seems distant in time and mentality from the neo-avant-garde artists of Hungary or the Viennese Actionists, for whose works the term is usually applied.

(3)In an interview posted at the show, ! Omara Occupies the Sound Space, János Sugár remembered how Omara had called him to say she was going to ‘make a scandal’ at her exhibition opening. Pócsik, Andrea (2021), ‘Egymás határtárgyai’, unpublished interview with János Sugár.

(4) ! – Omara hang-tér-foglalása [! Omara Occupies the Sound-Space], 4–29 May 2021, Kesztyűgyár Közösségi Ház, Budapest, curator: Andrea Pócsik. See https://offbiennale.hu/en/%7Byear%7D/program/1-program-romamoma.

Text: Veronika Molnár

Leave a Reply