Re-Enchanting the World: Collaboration instead of Competition

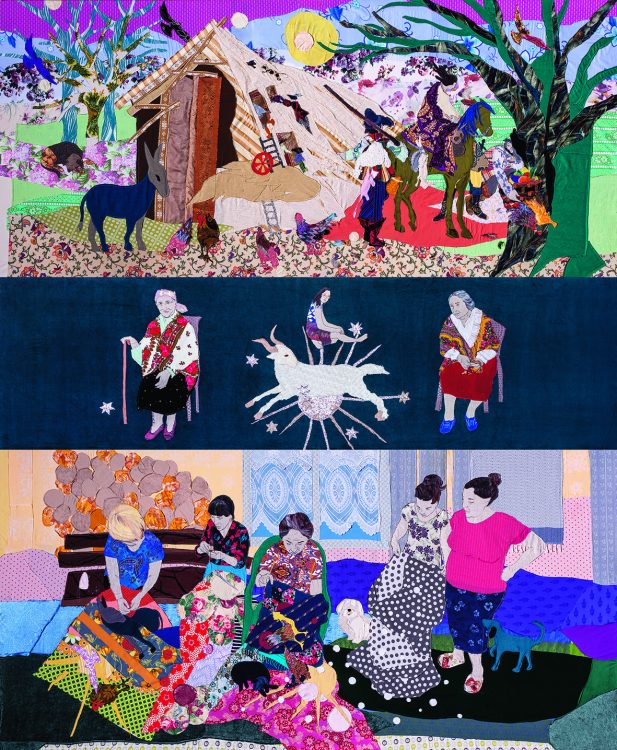

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas: Re-Enchanting the World, detail, 2022. Photo: Daniel Rumanicew, Polish Pavilion press materials.

Interview with Wojciech Szymański and Joanna Warsza, co-curators of Małgorzata Mirga-Tas’s exhibition in the Polish Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale.

What is the exhibition concept and the journey behind it?

Wojciech Szymański: The concept for the exhibition Re-Enchanting the World was born late last summer. On the one hand, with its title, the exhibition refers to Silvia Federici’s book, Re-Enchanting the World: Feminism and the Politics of the Commons (2018), which inspired us somewhat. On the other hand, the concept of arranging the exhibition itself, and the form it took, recalls the Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara. The pride of the Palace is the Hall of the Months, with a series of twelve panels depicting, in calendar form, scenes from the life of the patron Prince, Borso d’Este, interspersed with images inspired by mythology, philosophy and astronomy.

Joanna Warsza: Palazzo Schifanoia is where the art historian Aby Warburg developed his famous concept of iconology, putting images in perspective and in various contexts. He traced the migration of astrological figures from India, Persia, through ancient Greece, to the Renaissance. The Ferrara frescoes inspired the Warburgian concept of Nachleben, or the “afterlife” of images. According to Warburg, an image is not something fixed, assigned to one culture or place. He reconstructed the long journey of some of the motifs appearing in Ferrara through space and time. As one might expect, his analysis lacked any mention of Romani culture, even though the Roma, who migrated from India to Europe, played a very important role in this transport of meanings. These omissions and blind spots are the starting point for our exhibition. Małgorzata Mirga-Tas (MMT) was inspired by Palazzo Schifanoia and its structure of meaning to re-activate the mechanism of the wandering of images and to revive symbols important to herself and to Roma culture, to perform an operation from cultural appropriation to cultural appreciation of the largest European minority. Reaching for this very important reference in the art history is an attempt to add, to complement, to weave – in a literal sense, because it is a technique of working with fabric that MMT uses, often combining seemingly incompatible elements – threads of Roma culture into art history and into contemporary transnational art.

What was Małgorzata Mirga-Tas’s process of working on this ambitious exhibition?

WSZ: Inside the Polish Pavilion, MMT has built her own private “palace of images”, as Ali Smith called the Palazzo Schifanoia. The structure known from Ferrara has become a narrative machine for MMT, a kind of vehicle for telling her own stories. The exhibition is a kind of installation, consisting of twelve large-format pictures, created in the typical MMT technique of textile collage, and divided, like the original frescoes from Ferrara, into three horizontal bands. The upper band tells the story of the arrival of the Roma to Europe. The middle one is the band of female power and the feminine power to re-enchant the world, in which we find portraits of Roma women and friends of MMT separated by images of astrological signs. The lower part depicts scenes from the life of today’s Czarna Góra, the artist’s hometown. MMT used a recycling technique, making use of 15th century frescoes and Warburg’s concepts, combining fabrics from thrift shops, materials donated by people and from Zakopane’s Imperial Hotel, which housed the artist’s temporary studio during preparations for the exhibition.

Can Małgorzata Mirga-Tas re-enchant the world – and how?

JW: We treat art as a seismograph, and MMT’s art is very sensitive. Both Alemani’s curatorial concept and our Pavilion, although their concepts were born independently of each other, are part of the same conversation, the important topics of our time, such as women’s and minority rights, the decline of the Anthropocene and its impact on the destruction of the Earth’s natural resources, the place of native and vernacular art, and the paradigm of non-violence, among others. The art of MMT, who never separates her work in the field of art from her role as an activist or social activist, has always been and remains highly political. This is evidenced both by her return to her hometown of Czarna Góra, despite the fact that she could live anywhere from Berlin to New York, and by her involvement with the Roma community, such as the creation of a monument commemorating the extermination of the Roma in Borzęcin. At the same time, MMT’s involvement in highly visible art-world projects like the Berlin and Venice Biennales never stopped her from being active and involved in her community and practicing what Roma scholar Ethel Brooks calls the feminism of minority, made from within one’s – often patriarchal – community. MMT invariably positions herself as a deeply politically engaged artist, even if she does so in a very subtle, non-aggrandizing way. Her art is re-enchanting in the sense that it avoids confrontation mode, and is appreciated by people from all segments of the political spectrum. This art is inclusive, and has reconciliatory qualities, just like the needle she uses as a tool that performs rehabilitation, that repairs and mends. MMT’s patchworks are made up of elements that don’t fit together and yet coexist and create another extraordinary dimension. These elements do not fit, and they do not have to, and this is their strength.

What is the relationship like between Małgorzata Mirga-Tas and the viewing public?

WSZ: What is also important is that the work of MMT receives overwhelmingly positive feedback from a very general audience, people not necessarily interested in art and not connected to the art world. This art might seem easy and nice, but at the same time it is iconographically complex and packed with meaning and cultural associations. While still an artist just trying to make a name for herself, MMT was sometimes treated with disrespect by some people in the art world who saw this kind of figurativeness she has proposed and working with textiles as a risky, not contemporary enough artistic practice, or a sign of conservatism, and as a result MMT’s artistic expression was orientalised and exoticised quite often. It is possible that those making such accusations were unaware that such accusations were made until the beginning of the 21st century against many artists who rejected the post-conceptual, and post-minimalist lingua franca of contemporary art and did not use the artistic language of global north or global western art, forcing them to talk about their minority identity using the majority language. MMT, too, has chosen to reject this majority idiom: she has decided to speak her own language and has been very consistent in doing so over the years. This language has finally been heard, and hopefully it will also be received with understanding. It is an attempt to teach/introduce into the art world a certain polyphonicity, a certain multidirectional memory of images, using these images to then create new content. MMT is someone who, also outside the art world, has an unparalleled ability to performatively hack reality. I do not mean to say that MMT is a performer, but I mean that her way is to position herself in a broader context, in everyday life, where she provokes us to rethink, disenchant and re-enchant the world. On the one hand, MMT represents Poland at the traditional Biennale, which is a bit like the Olympics, with all the pomp of national representations, official delegations and pavilions. And it is great that a Romni represents Poland, being at the same time the first Romni in the history of the entire Biennale to exhibit in a national pavilion. On the other hand, if we think of Roma as a transnational community, MMT’s participation invalidates national representations and the notion of playing under one flag. This pavilion proposed by MMT belongs to everyone and invalidates the rules of the game that govern Venice as the Olympics of the art world.

Graphic design: Agata Biskup; photo: Daniel Rumiancew. Hall of the Months, Museo Schifanoia, Ferrara, courtesy Musei di Arte Antica di Ferrara.

What is the significance of featuring a Roma artist at the Venice Biennale?

JW: We don’t treat the Biennale in terms of an Olympics. On the level of content, MMT’s proposed reinterpretation of Palazzo Schifanoia demonstrates the Roma’s contribution to the European community. The Roma, despite their number – 10-12 million in Europe – are one of the most discriminated and marginalised minorities, and their contribution to European culture is often erased. We hope that by showing the Roma as a transnational, proto-European community, not only Poles, Swedes or Ukrainians will be able to find themselves in this Pavilion, but all of us as Europeans. The re-enchantment that MMT has to offer is a vision of cooperation instead of competition, non-violence instead of building muscle. Showing that the majority culture can learn a lot from the minority, whose field of vision is often wider, which makes it possible to recognise phenomena unnoticeable from the perspective of privilege and stability. In the European context, MMT displays and embodies the issues of transnationalism, pacifism, nonviolence, feminism, and ecology, both in the values communicated, and in the stunning visuality, in the richness of the colours, that makes this art universally appealing. One builds a connection with this art, which captivates the audience without the need to read a complicated curatorial text, and yet, if you were to write a PhD about it, the number of layers and topics is endless.

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, a scholar tracing the so-called imperial militarist mindset, introduces the concept of potential history as an alternative to the common history based on violent logic and told mostly by the victors. Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, speaking of potential history, looks at the moments which have not resonated, which have been erased from collective memory, but which could serve as a starting point for reworking, in a non-violent way, relations between the beings inhabiting our planet. One of our questions is whether a Roma refusal to engage in nationalistic and military operations and living a life of forced exile is a moment of a potential history.

WSZ: In this sense, it is this potential history, the never-told story of the Roma through the Polish Pavilion and MMT’s exhibition, that is actualised in the present, and it is an attempt to hack it, to change the optics, to show that one can see the past differently – the upper band is the historical past – as well as the present, to look at completely different, new images/narratives generated by this palace of images. This is the most important question we would like to ask: how we can change the way we think about ourselves, not as self-determining entities, but as interdependent ones? We hope that the stunning richness of this exhibition will bring you closer to this emotional experience.

Wojciech Szymański, PhD, is an Assistant Professor at the Institute of Art History at the University of Warsaw, Poland. He is an independent curator and art critic; member of the International Association of Art Critics AICA; author of the book, The Argonauts: Postminimalism and Art After Modernism: Eva Hesse – Felix Gonzalez-Torres – Roni Horn – Derek Jarman (2015; in Polish), as well as over 40 academic and 100 critical texts published in exhibition catalogues, art magazines, and peer-reviewed journals and monographs. He has curated over thirty group and solo shows and art projects, including several exhibitions of Roma contemporary artists and Roma art. His research interests include queer studies, Central European art history, postcolonialism, heritage and museum studies. He is co-curator of Małgorzata Mirga-Tas’s exhibition in the Polish Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale (2022).

Joanna Warsza is Programme Director of CuratorLab at Konstfack University of Arts in Stockholm, and an independent curator and editor, interested in how art functions politically and socially outside the white cubes. In 2021, together with Övül Ö. Durmusoglu, she co-curated Die Balkone in Berlin the 3rd Autostrada Biennale in Kosovo, and the 12th Survival Kit in Riga (LV). She was the Artistic Director of Public Art Munich 2018, curator of the Georgian Pavilion at the 55th Venice Biennale, and associate curator of the 7th Berlin Biennale, among others. Her recent publications include: Red Love. A Reader on Alexandra Kollontai (co-edited with Maria Lind and Michele Masucci; Sternberg Press, Konstfack Collections, and Tensta Konsthall, 2020), and And Warren Niesłuchowski Was There: Guest, Host, Ghost (co-edited with Sina Najafi; Cabinet Books and Museum of Modern Art Warsaw, 2020). Back in 2012, she realised the exhibition, Project, focusing on Roma culture at Wielkopolskie Rewolucje festiwal in Konin, Poland. Originally from Warsaw, she lives in Berlin.

Interview by Katarzyna Pabijanek for RomaMoMA

[…] Previous Blog Entry […]