Can We Live Together? Can We Sing Together? Of Alamo, Love and Loss

Movie still from ‘Vengo’, a film by Tony Gatlif (2000)

Everyone belongs elsewhere, and elsewhere could mean both everywhere and nowhere. Sung by Remedios Silva Pisa, Yasmin Levy, Eleni Vitali, Emel Mathlouthi, Zeynep Bastik and others, ‘Naci en Alamo’ (‘I was Born in Alamo’) is a Ladino–Greek Romani ‘song about displacement and homelessness, and ultimately about nostalgia for a birthplace that was never home’ (Aciman 2011). There are countless suggestions as to its original provenance, what ‘alamo’ means and where it is, or why the singer pronounces it as ‘el amor.’

No tengo lugar

Y no tengo paisaje

Yo menos tengo patria

Con mis dedos hago el fuego

Y con mi corazon te canto

Las cuerdas de mi corazon lloran

O tengo lugar

Y no tengo paisaje

Yo menos tengo patria

Con mis dedos hago el fuego

Y con mi corazon te canto

Las cuerdas de mi corazon lloran

Naci en alamo

Naci en alamo

No tengo lugar

Y no tengo paisaje

Yo menos tengo patria

Remedios Silva Pisa’s version of the song became well known in Western Europe thanks to Tony Gatlif’s Vengo (1999), a film about a blood feud between two Romani families, shot in Andalusia. The original version of the song was not sung in Spanish at all but, as the film credits show, in Greek. It was composed as ‘Balamo’ or ‘To Tragoudie Ton Gifton,’ in around 1992 by Dionysis Tsakni. Or maybe it wasn’t; there are diverse assertions about its origins. Alamo is a town in Andalusia, on the Portuguese border near Seville, and there are other Alamos in Portugal as well, while the word also means ‘nowhere.’ In Greek, balamo means ‘stranger’ or ‘alone.’

Belonging everywhere and nowhere is generally considered an attribute of Romani communities that live without borders and the notion of property. ‘The verb “gyp,” a derivation of “gypsy,” means to cheat or swindle. Its derogatory implications reflect a reality in which nomadic existence is seen as a threat to the social order and its ‘institutions’ (Durmuşoğlu 2020). The past decade has witnessed millions of people fleeing their homes, moving towards Europe, across the sea, trying to stay alive and to find a decent life. As a result, belonging everywhere and nowhere, as an everyday crisis and form of resilience, has deeply agitated societies in Europe, setting off ferocious ultra-nationalistic, alt-right reactionary politics. Yet everywhere and nowhere, as a notion of the soul, is part of the collective vocabulary for many born on the Levant or the eastern Mediterranean, in different religions, traditions and languages (such as Arabic, Hebrew, Greek, Armenian, Kurdish, Aramaic and Turkish), creating a keenness for an unfamiliar familiarity.

Film “VENGO” by Tony Gatlif – Song “Naci En Alamo” by Remedios Silva Pisa.

My first time in the old city of Córdoba was a state of unfamiliar familiarity, which made me feel as if I were elsewhere—which could be everywhere and nowhere. As someone who was born into the ancient cultures of the eastern Mediterranean and grew up with a liberal secular Muslim education in Turkey, that is not an unfamiliar feeling. It may have been due to the narrow labyrinthine streets that lead to La Mezquita Cathedral, or, The Great Mosque of Qurtuba, or the citrusy scent in the air, or the awkward Roman columns in the middle of a clumsily modern square, or the way locals speak to each other while hosting foreigners.

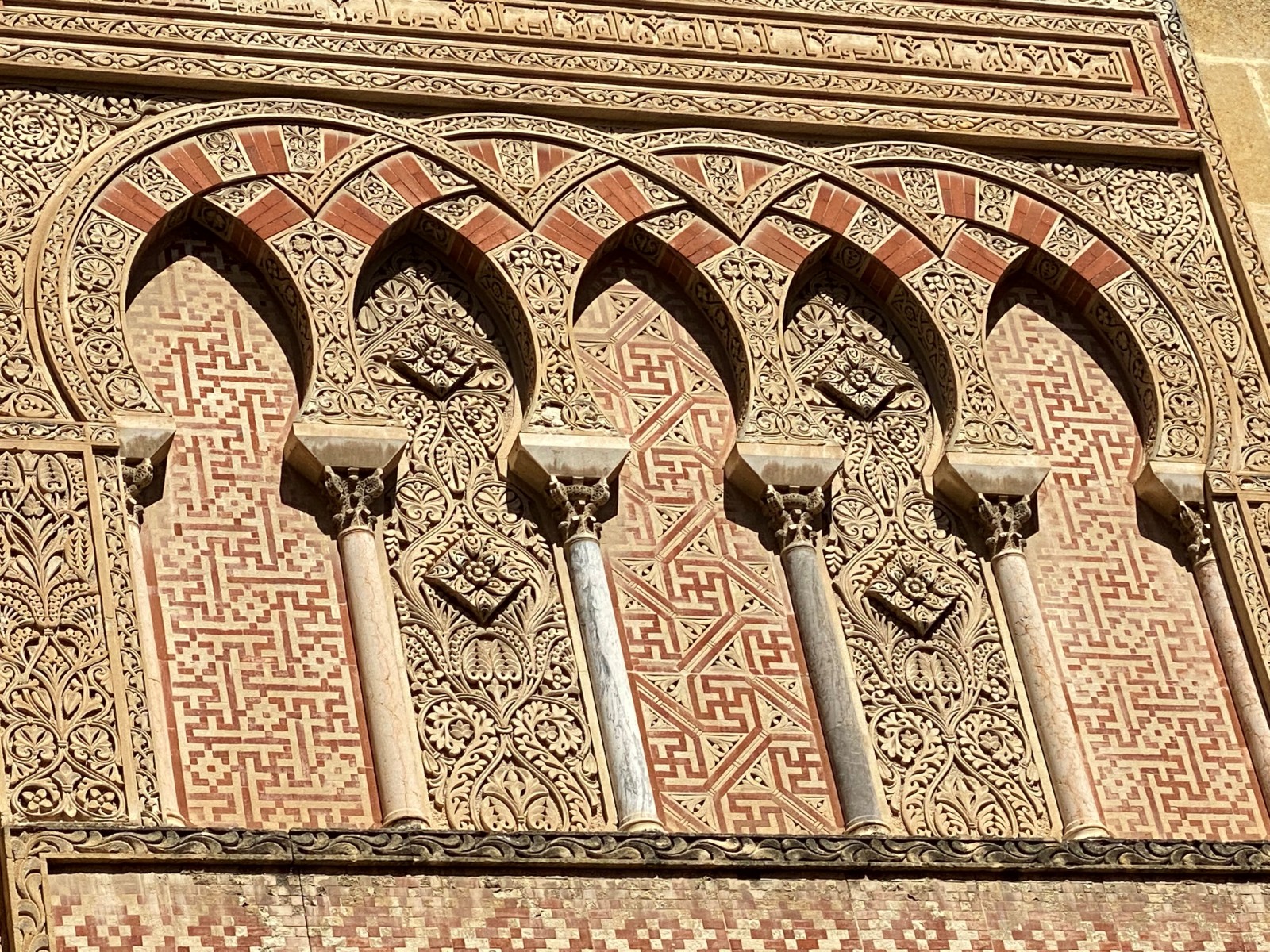

There is a cosmological precision to La Mezquita—a bold and unique hybridity that is shaped by the interaction of all the different elements, histories and forms, their breathing together inside the cathedral. Arab literature and philosophy attributed aesthetic superiority to the colours red and white, the former associated with life, the latter with purity and luminosity. The 8th-century red-and-white arches symbolize the endless and eternal power of the divine as they still stand to support this unique exercise in continuity, proximity and adjacency. Built on the remains of a modest Visigoth Church of St Vincent, La Mezquita re-enacted the story of the Great Mosque of Damascus, which was erected on the site of the Church of St John the Baptist—and each Christian place of worship had been preceded by a Roman temple. The orange trees in the open courtyard were planted to evoke a homeland that was far away in Syria.

The tall palm tree in the courtyard of the exquisite Chapel of San Bartolomé in the Jewish district of La Judeira seems like an old witness to older times. Inside, the chapel is ornamented with colourfully glazed ceramic tiles and Kufic inscriptions, making it a prime example of Mudejár art, itself named after the Muslims of the former Al-Andalus who did not leave after its Christian reconquest in the later Middle Ages. ‘To give the new State the necessary representative and residential architecture, the Umayyads also transposed to Qurtuba [and Madinat al-Zahra] the Syrian palatine constructions of Byzantine, Hellenistic and Middle East tradition’ (Vílchez 2013, 39). It is claimed that at first many Christian masters were invited from the Byzantine Empire to realise these edifices, which adds to the multilayered syncretism.

Córdoba, Photos by Övül Ö. Durmuşoğlu

Forms and acts of syncretism can take place in the space of living together not only as harmony but also as confrontation and resistance. ‘Can we live together?’ is a such a burning question of our time. There are many books, texts, artistic and architectural practices, exhibitions contemplating the question, attempting to come up with more positive answers. In his now classic text, Can We Live Together?: Equality and Difference (originally published in 1997), philosopher Alain Touraine highlights the fact that though we watch the same TV shows, buy similar clothes and speak one lingua franca, they do not unite us in a single global society (Touraine 2000, 1). We do not communicate with each other in a meaningful way as many societal structures break under the stress of ethnic, political and religious conflicts. From the perspective of modernity, its nation states and new models of sovereignty, the period of La Convivencia, a term ‘proposed by the Spanish philologist Américo Castro, regarding the period of Spanish history from the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in the early eighth century until the expulsion of the Jews in 1492’ (Convivencia 2023) under Catholic rule, appears to be a more or less utopian exercise. The Spanish Jews who chose to leave Spain instead of converting dispersed throughout the region of North Africa. Many Spanish Jews fled to the Ottoman Empire where they were given refuge and settled in Thessaloniki, Izmir and Istanbul, among the pearl cities of the Levant.

Much later I learned that Abd al-Rahman I, who transformed ‘the former Roman and Visigoth city into the “capital of Al-Andalus” (qa‘idat Al-Andalus) and “government seat” (qa‘idat al-mulk) of the new and first Islamic state of the Iberian Peninsula’ (Vílchez 2013, 30), was nicknamed al-Dakhil, ‘The Immigrant,’ the one who came from the outside, the stranger. He escaped the ‘massacre of his family by the Abbasids, who had just overthrown the Damascus Caliphate (751) and were about to establish their own caliphate in Baghdad’ (Guichard 2015, 11). What brings me to elaborate on glimpses of Córdoba is curiosity about a multifaceted social, political, theological and aesthetic entity that is a particular blend where three Abrahamic belief communities, together with the Roma, mutually changed each other, rather than a blunt romanticization of La Convivencia. A fine period of human thought when different resources to understand the world met through translation, from Greek to Arabic, Hebrew and Latin. It became possible when paper arrived in Spain (alongside Sicily) in the 11th century, thanks to the Arab traders of Al-Andalus. The Arab world had found out about the secrets of papermaking in 751 AD—35 years before the construction of the Grand Mosque of Qurtuba began—‘when the governor-general of the Caliphate of Bagdad captured two Chinese papermakers in Samarkand’ (Cantavalle 2019).

Historically, the ‘emblematic splendour’ Cordoba had reached by the 10th century as an immense and prestigious capital that expanded for 15 kilometres along the river Guadalquivir ‘did not last more than a few decades, and the city never recovered the prestige it had enjoyed in the second half of 10th century’ (Guichard 2015, 8). Yet within this shining period of expansion it was possible to think, to build and to produce together. It makes me think of a certain sense of community, different from what is understood as identity politics, which we fail to exercise and maintain in our contemporary societies. Such an understanding of living lies at a great distance from the violent extremities and polarizations that are kept alive by race, religion and the class divisions of extractivist capitalism.

As large groups of tourists float to queue in front of La Mezquita, the streets of Córdoba and the river Guadalquivir hold on to their many untold and unstudied stories of ‘elsewhere.’ A stranger from the outside came and transformed the fate of the cosy city by the river. The river that brought the Immigrant from North Africa enabled the establishment and consolidation of colonial imperialism in a few centuries. The journey of ‘Naci en Alamo’ from Greece to Andalusia shows that the practice of ‘la convivencia’ mostly takes place in music and poetry. Just like an ancient Greek tragedy, music sets the emotional pace and tone of Vengo as interwoven textures of deep flamenco prepares the audience for what comes next. The film opens with two rowing boats with well-dressed people in them crossing a river, while a lutanist and a ney player engage in a dialogue. Reaching a dilapidated church on a hill, they all attend a flamenco session, where Sufi singer Ahmad Al-Tuni and a Sufi dancer soon join in for what is a most memorable music-driven opening scene. The space of that performance is timeless and vibrant unlike the audience following it. One cannot help asking whether this scene also displays a form of mourning for a practice of living together that is long gone. In Vengo, the Guadalquivir always appears as a protagonist, communicating the essential story of love, loss, pain, anger and despair, which we all share and which make us human.

Entitled ‘Drinking Poem’ and written by Ibn Sirāj, who died in Córdoba in 1114, these beautiful line speak of the light, valleys, skies, stars and the night around Guadalquivir:

When I saw the day

going off dying

and night approach

full of youth

when the sun was sprinkling

the last saffron rays

over the hills

and beginning to sift shadows

of black musk powder

over the valleys

then I caused the moon of wine

to come out.

You were the planet Mercury

and our guests, accompanying stars

(Franzen 1989, 53).

In the soundtrack of Vengo, ‘Naci en Alamo’ feels to be close to cante jondo, the ‘deep song’ of Andalusian flamenco. They sound as if they hailed from the same place, a home that is long gone, or has moved inside the human heart. No wonder it has been sung so fervently by Sephardic Jewish, Greek, Turkish and Tunisian singers around the Mediterranean, calling for home. As I finalize this text, the war in Gaza has already claimed ten thousand lives. Another ancient eastern Mediterranean city with all the lives and dreams it has held is about to collapse, to be added to the debris of violent modernity. And the need for imagining other exercises in ‘convivencia’ is at its most urgent. At the end of the day, we need to remember: Everyone belongs elsewhere, and elsewhere could mean both everywhere and nowhere.

<<Originally commissioned for Meandering, ed. Sofia Lemos, London: Sternberg Press, 2024.>>

References:

Aciman, André (2011), ‘Convivencia’, Tablet Magazine, https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/arts-letters/articles/convivencia, accessed 1 Nov. 2023.

Cantavalle, Sarah (2019), ‘The History of Paper: From Its Origins to the Present Day’, The Pixartprinting Blog, https://www.pixartprinting.co.uk/blog/history-paper/, accessed 1 Nov. 2023.

‘Convivencia’ (2023), Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Convivencia&oldid=1179197419, accessed 1 Nov. 2023.

Durmuşoğlu, Övül Ö. (2020), ‘Delaine Le Bas’, https://11.berlinbiennale.de/participant/delaine-le-bas, accessed 1 Nov. 2023.

Franzen, Cola (1989), Poems of Arab Andalusia (San Fransisco: City Lights Books).

Guichard, Pierre (2013), ‘Cordoba, from the Muslim Conquest to the Christian Conquest’, AWRAQ, 7, 1: 7-27, http://www.awraq.es/blob.aspx?idx=6&nId=87&hash=c0f21a00feda9892ddff3275ea63027c, accessed 2 Nov. 2023.

Touraine, Alain (2000), Can We Live Together?: Equality and Difference (1997), trans. by David Macey (Stanford: Stanford University Press).

Vílchez, José Miguel Puerta (2013), ‘Qurtuba’s Monumentality and Artistic Significance’, AWRAQ, 7, 1: 29–67, http://www.awraq.es/blob.aspx?idx=5&nId=89&hash=d4368e9867c44946f5b17e06696066da, accessed 1 Nov. 2023.

Leave a Reply