Reinventing the Romani wheel: a visual essay on the history of Rom*nja under socialist rule

Averklub Collective: Manuš heißt Mensch (2.6 – 5.9.2021), installation view Kunsthalle Wien. Photo: eSeL. See: https://kunsthallewien.at/ausstellung/averklub-collective-manus-heisst-mensch

Blue on the top, green on the bottom, a red star in the centre. At first glance, the poster for the exhibition, Manuš heißt Mensch – Manuš means human, seems to aim for a clear connection to the Romani flag, and therefore a perspective on Romani activism and politics. On closer examination, however, the question of the ethnicisation of art and culture is raised throughout the whole display. Is all art created by artists of Romani origin a priori Romani art? Who defines the narrative, and who is entitled to tell a certain story? And most importantly, what is art capable of?

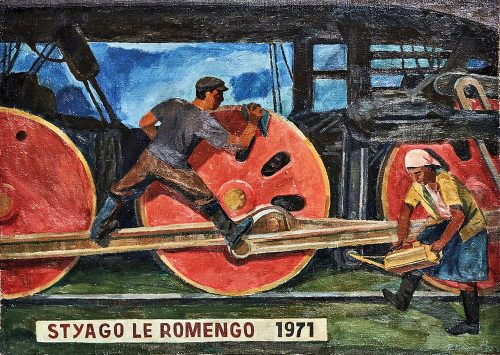

Replica of the Yugoslavian Rom*nja flag, 1971.

Vienna, summer 2021. While walking down the streets of the Austrian capital, it is hardly possible to miss a certain sentence, plastered in capital letters on billboards all around town. Manuš heißt Mensch – Manuš means human is the title of the most recent exhibition by artists of the Czech Averklub Collective, on view at Kunsthalle Wien, the exhibition hall for contemporary art in Vienna. The work focuses on the Romani settlement of Chanov in the northwest of the Czech Republic. The artists examine various thematic fields, including work, history, art, politics and emancipation through artwork and theoretical research.

A different collective

The artists behind the exhibition, Manuš means human, consist of a collaboration of the Romafuturismo Library – a project focusing on Romani literature aimed at the emancipation of ethnicities and cultures experiencing discrimination – and the Aver Roma association, meaning “different Roma” in Romanes. This cooperation marks the foundation of the Averklub Collective, a loosely organised group, whose 13 main members were once residents of the Chanov housing estate in Most, Czech Republic. Today they dedicate their work to the identity and realities of people living in the country’s largest Romani settlement.

Examining socio-political questions in the past and present of the Czech Republic, and focusing on marginalised spaces and supressed groups, the collective aims to shine a light on the history of the Romani people, which all too often has been forgotten or silenced. Manuš znamená člověk (Manuš means human) is the title of a publication by Czechoslovak Romani politician, Vincent Danihel. The collective takes this book, which deals with the historical development and status of the Romani people, as an inspiration for the exhibition, thus creating both a context for the living conditions of Czech Rom*nja under the communist regime and simultaneously for the idea of equality and equal treatment of human beings in general.

The exhibition hall for contemporary art in Vienna, namely the Kunsthalle Wien, is a prestigious and central location within the walls of the Museum Quarter of the city. It is all the more pleasing that the work of a Romani artist collective is displayed at such an institution. However, it is also not a space free of privileges and barriers for its visitors, and therefore clearly not fully accessible for marginalised groups, which stand in contrast to the collective’s idea of equality. When being asked about their vision for the target audience of the exhibition, the artists stated: “We are realists. This is an exhibition for the average visitor to the Kunsthalle Wien: in the vast majority of cases, that means an educated, liberally inclined, middle-class audience. We are not in a position to wish for anything more. The institution of contemporary art has its limits, and these are not related to barrier-free access or the price of a ticket”.

Let’s be realistic

In order to contextualise the exhibition, Manuš means human, Andrea Hubin – cultural mediator of the Kunsthalle Wien – and Melinda Tamás – non-formal education trainer and member of the Austrian Romani community – created a well thought-out concept for workshops, excursions and tours. Local Austrian Romani activists and artists, such as Gilda-Nancy Horvath, Katharina Graf-Janoska and Žaklina Radosavljević, provided thrilling insights into topics such as work, literature, organising emancipation and image politics for participants of the workshops. Together, they examined whether objects are an expression of a culture, or if they rather convey stories of social conflict, contradictions and inequalities.

Rozana Kuburovič: Rom*nja-Flag, 1971. Private collection.

Running circles

Prior to entering the exhibition, a stylised wheel awaits the visitors of the art hall. The red wheel is deconstructed into individual parts and eventually formed into a red star. Playing with the chakra, a symbol of both Romani activism and also stereotypes concerning nomadism and the freedom to travel, the artists pay tribute to the international Romani flag. With the evolution into a red star, symbolising socialism in Czechoslovakia, the artists aim to emphasise the endeavours of the communist regime to integrate Romani people into a socialist Czech society and to allegedly better their living conditions. This theoretical contrast between today’s anti-gypsyist society and a presumably more inclusive environment within the totalitarian Soviet regime is mirrored throughout the display. As an example, the international Romani flag is shown next to an alternative approach of a flag for Romani people, namely the red chakra switched out for a socialist red star.

Six different chapters of the exhibition are loosely sorted and arranged into colours. Concentric circles guide the visitors to view the displayed pieces from the inside out or inversely. The section, He Who Does Not Work Shall Not Eat! outlines the depiction of labour within the Romani community in the second part of the 20th century and the evolution of the concept of labour and its effects on a marginalised community. Questions of belonging and housing are raised within the section, The Gallows Drop and the Firm Ground of a Home, bringing the Romani settlement of Chanov into focus. Stalin My Brother: Soviet Literature deals with the approaches of alphabetisation of Romani communities and the codification of Romanes in the Soviet Union. Further, the chapter, The History of Art, without History and without Art, examines the absence of Romani art within a predominantly white-coined art history and the exclusion of art from a mainstream narrative of the majority society. While the chapter, Lenin Was Not a Rom, plays with stereotypes of exile and nomadism, the section, Did Someone Say Something about the Emancipation of the Roma? focuses on the civil rights movement of Rom*nja in the Czech Republic and Europe.

Rozana Kuburovič: The First Roma Congress, 1971. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Kunsthalle Wien

As co-curator, Frantisek Nistor explained at the opening press conference, the collective aims to show a level of belonging that goes beyond cultural diversity, gender or national heritage: a level of belonging, which is accessible for everybody without exception. The concept of the exhibition is very broad and quite specific at the same time. That said, even for people with expertise in the field of Romani art, history and politics, the message and the idea of the collective is perhaps not clear at all times. Although the artists aim not to ethnicise the topic of socialism and neoliberalism in the Czech Republic, they are not fully able to depict Romani people without generalisations and stereotypes within the display.

The idea that Romani people were treated inclusively within the socialist dictatorship in Czechoslovakia and emerged as the biggest losers of the political turnaround of the fall of the Iron Curtain is raised at many points throughout the exhibition. “We are also conscious of the confusing historical and conceptual associations that surround the word ‘socialist’, but we are prepared to risk being misunderstood”, the collective explains in the booklet accompanying the exhibition. The simplified account of communist rule in socialist countries, however, lacks a depiction of the horrors that several Romani communities had to suffer within the Soviet Union, romanticising a totalitarian regime. The exhibition, Manuš means human, is not fully able to answer the questions it poses, rather leaving visitors with more pending questions than they may have already had, going in.

Samuel Mago

Sources:

https://volksgruppen.orf.at/roma/meldungen/stories/3106577/

https://kunsthallewien.at/en/lets-be-realistic/

https://kunsthallewien.at/101/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Averklub-Collective_Ausstellungsguide_DE.pdf?x90478

Next Blog Entry

[…] Previous Blog Entry […]