Barvalo: Designing an Exhibition on and with Roma Communities in a French National Museum

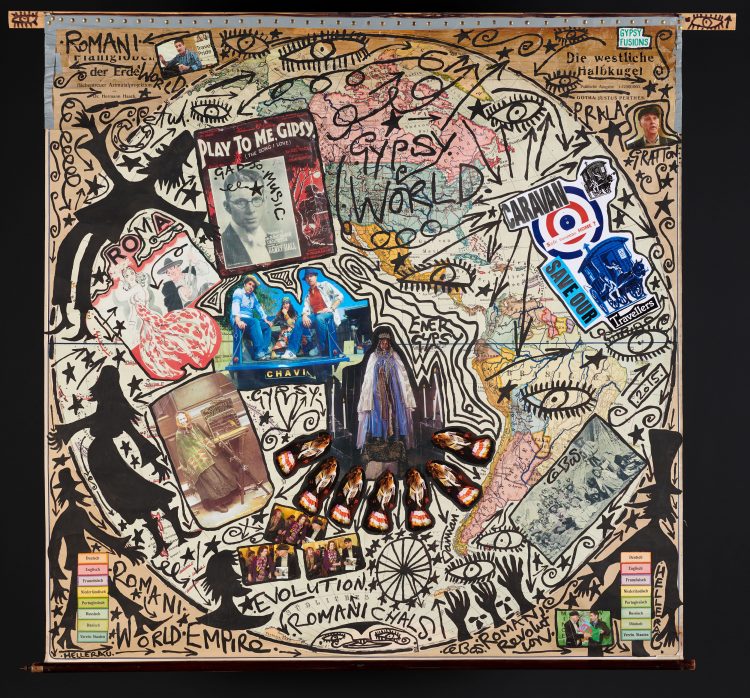

Damian Le Bas, Romani World Empire, 2015, collage and drawing on a map © Marianne Kuhn/Mucem. In 2019, Mucem purchased three collages by Damian Le Bas, following the acquisition policy decided in 2018 (commencing with the purchase of four paintings by Ceija Stojka): collecting Roma artists and challenging the ancient stereotyped ethnographical collections.

In 2023, Barvalo[1] will be held at the Museum of Civilisations of Europe and the Mediterranean (Mucem), in Marseille, in the south of France. This exhibition, focused on Romani cultures and professions, is designed in collaboration with Rom, Sinti, Gitano, Manouche and French Traveller representatives from France and across Europe. Through inviting Romani individuals to join in the creative process, this project does not simply aim, given the participatory trend in museums, at engaging in an “ethical washing”, with communities treated at best with exoticism and at worst with racism, but its objective is rather embracing a plurality of opinions and a wide range of expertise on the subject.

In 2017, an exhibition on Roma professions in Europe and the Mediterranean was programmed at Mucem (Museum of Civilisations of Europe and the Mediterranean), a French national institution based in Marseille, in the south of France. What had been planned as a relatively traditional project headed by two curators (one curator from Mucem paired with an academic expert from a university), backed by a scientific council, and accompanied by an ethnographic survey carried out by professional anthropologists,[2] emerged two years later as something of a completely different nature. The curatorial team was expanded to three curators (ERIAC being the third) and two assistants. The scientific council, traditionally made up of curators and academics, expanded beyond their habitual advisory function to become a full-fledged actor in the design of the entire project, with its members – Romani as well as non-Romani researchers and activists – becoming collaborators on the concept and exhibition design, investigators in the survey-collection (collecting data and objects to be exhibited), advisors in the production (the physical display process), and co-creators of the cultural programme (cinema, theatre, music, dance, etc.) held during the exhibition entitled Barvalo, from 18 April to 28 August 2023. The exhibition project was also enriched by a review (ethical acquisition and indexing) of Romani produced and/or Romani depicting objects in the Mucem collections, in consultation with representatives of Roma communities.

Valentin Merlin, Jasmine Picking, 2019, photography © Valentin Merlin/Mucem. This picture was taken during the survey-collection led by Lise Foisneau and Valentin Merlin, among Sinti flower-pickers for the Grasse luxury perfume industry, a savoir-faire acknowledged by the UNESCO label.

What happened between 2017 and 2019 to produce such a change? As Emilie Sitzia writes, “In recent decades, the production of knowledge has become a central issue for museums. This is partly due to the development of new forms of mediation centred on the visitor such as the new museology, constructivist approaches and participative practices”.[3] These changes are not only centred on the visitor, but also on the “source communities”, subject of the exhibitions. For the past ten years or so, the voices of Roms, Sinte, French Travellers, Gitanos, Manouches, Irish Travellers, etc. have been heard in Europe and throughout the world, denouncing the exhibitions and more broadly, the cultural projects of which they are the subject – and for which they have not been consulted at a minimum. The two original curators of the exhibition, as they commenced their research, gradually became aware of the importance of the “Nothing about us without us” movement, launched in October 2014 by the Romani Studies Department of the Central European University in Budapest,[4] of its weight, and above all, of its legitimacy.

Some museums, either spontaneously (the participatory approach is not a new concept), or having heard of this manifesto, since adopted this principle of participatory exhibition. The Vienna Historical Museum proposed a close collaboration to members of the Austrian Roma and Sinti communities in 2015, by entrusting them with the curatorship of the exhibition, Romane Thana, Orte der Roma und Sinti. However, there are legions of counter-examples of exhibitions realised without any consultation, or with only basic information, once it was no longer possible for the related communities to intervene on the content. In 2018, Mondes Tsiganes [Gypsy Worlds] at the National Museum of the History of Immigration in Paris drew international criticism from Romani activists. Most surprising is that these critics did not only emanate from intellectuals who signed the “Nothing about us without us” manifesto, but also from French associations who had never even heard of it, but fought daily for the equal rights of Voyageurs and other Romani communities. What was questioned was not the quality of the exhibition’s scientific work – which was excellent, but the reinforcement of the visitor’s unconscious anti-gypsyism, which, paradoxically, the curators tried to denounce by explaining how the stereotype of the “Gypsy” is constructed. Incorporating a Romani perspective at the initial stage of project design could have prevented this pitfall.

In and of themselves, participatory projects are not unheard of in French cultural institutions. In fact, the eco-museums, society and regional museums, which flourished in France after the concept was defined by ICOM in 1971, are the pioneers of public participation in heritage institutions. These projects make it possible to generate and maintain connections between populations, but also to collect, conserve and share local heritage. The conservation and presentation of this heritage, however, is not generally left to the public, but entrusted to specific and qualified personnel, namely curators, conservators and university researchers.

Thus, the idea of participation is not new to Mucem. Many initiatives with museum audiences have indeed emerged since 2013, the year of the opening of the museum. Already before 2013, the institution had carried out several local consultation operations in order to understand the desires of future visitors, to draw up the contours of the museum of their dreams. During these seven years of existence, participative projects have multiplied to the point of entrusting a group outside the institution with the integral design of a project.[5] But never has this been done, thus far, by putting this creation in the hands of a “vulnerable”[6] group, of a community whose existence is fragile within society. This is why the exhibition projects, such as Barvalo and HIV/AIDS the epidemic is not over! which are carried out at the same time at Mucem, forge a new path, but a complex one. Not only because such projects are very long (and expensive) to be carried out: working with dozens of volunteers whose occupations are not generally building an exhibition is much more time-consuming than working with two curators devoted only to this objective. Hence, the six years of preparation (including the unexpected effects of a world pandemic).

Workshop “Choosing the title of the exhibition”, held in February 2020 with the experts of Barvalo and Mucem “Communication Department”. © Sandra Barbier/Mucem.

In reality, the fact of building a collaborative project in France with representatives of the Romani communities is itself delicate. This is for two reasons. The first is that the French state does not recognise ethnicity. We are all French, and not Breton and French or Roma and French. It takes just one step from ethnicity to communitarianism. Communitarianism is a danger, a principle which threatens the very foundations of the French Republic. How can one thus invite to a national museum, therefore representing the thinking of the State, an ethnic group that everyone considers withdrawn?

All the more so, and this is the second reason for the difficulty in having a project like Barvalo spring up: the different Romani communities present in the country are not really politically united.[7] Moreover, as Mucem aims to deal with European and Mediterranean subjects, we wanted to include the populations of the whole of Europe, while the French groups are very reticent with respect in particular to the Roma of the East, whose unifying point (We are all Romani) is perceived in a hegemonic way by the French Travellers,[8] Gitanos, Manouche and Roma from France, who feel French above all, and fear that the unifying speeches of international Romani intellectuals will disturb the already unflattering image that the French Gadje have of Travellers. Because in the head of a French Gadjo, belonging to the Gens du Voyage community is bad, but it is even worse to be “Roma from India” that are regarded as people who came to beg in the French streets with their children and engage in mafia trafficking! It is therefore difficult in these conditions to get together Romani representatives with such different objectives: to put it simply, the Travellers want the exhibition to inform about them and promote them, avoiding conflation with other non-French populations; the international representatives have a transnational vision of Romanipe which they want to share with the Romani as well as the Gadje. But all aim to change the way the Gadje look at them – and this is what makes the collaborative dynamic work!

Despite these structural difficulties, and with the support of Mucem’s management, we were able to bring together 16 Romani and non-Romani experts, men and women, scholars, non-scholars, but all activists. The curatorial team was careful to invite representatives of the different communities living in France, and more particularly in and around Marseille: Roma, Sinti, French Travellers and Gitanos. Roma representatives of international reputation, who stood out in their academic work as well as in their fight for the recognition of the rights of the Romani populations, were also invited. In sum, ten participants of Romani origin are involved in the project, from all over Europe (France, Italy, Romania, Hungary, Poland, United Kingdom) and different Roma groups (Roma, Sinti, Gitanos, Manouche, Travellers). If at the beginning, due to the different positions we mentioned above, the conceptual workshops for the exhibition were a bit tense (even more so, as the non-Roma experts did not feel legitimated), a respectful and cordial work dynamic developed. Its benefits are incredible and Barvalo will undeniably be a richer and more complex exhibition than the one it would have become if it had been maintained as planned in the 2017 project‚ Romani Professions and Know-How in Europe and the Mediterranean.

Julia Ferloni is a French curator and specialist in the art and societies of Oceania. She taught this discipline at Ecole du Louvre in Paris, and published several popular books and articles on the history of the discovery of the Pacific. She also initiated the reopening of the anthropology gallery of the Museum of Natural History in Rouen, and was curator of its section devoted to Oceania with Te Papa Tongarewa, National Museum of New Zealand (2011).

From 2011 to 2014, Julia Ferloni headed the scientific hub of the Interdisciplinary Centre for Conservation and Restoration of Heritage (CICRP), based in Marseille. She then joined the Museum of Civilisations of Europe and the Mediterranean (Mucem) as head of the Craft, Commerce and industry Collection, and curator of L’Amour de A à Z (Love from A to Z, 2018) and Barvalo (2023). She specialises in accompanying participatory projects in museums.

[1] In Romani, barvalo means rich – physically as well as culturally, and proud.

[2] Mucem’s survey-collections develop and expand the museum’s exhibitions with artefacts and documentation. Those will ultimately join the National French Collections, which are inalienable and imprescriptible (French Museum Law, 2004).

[3] Sitzia, 2018, p.142.

[4] Finally forced by the current Orbán government to re-locate to Vienna.

[5] For instance, the exhibitions co-curated with secondary-school pupils: Rêvons la ville (2017), Osez l’interdit (2019), and Derrière-nous (2020).

[6] On vulnerable communities’ inclusion in participatory projects, see: Cornwall, Andrea, 2008.

[7] Except for the case of the Gens du Voyage Advisory Committee, which is more concerned with issues of equal rights than with cultural projects.

[8] All the more so, as the Voyageurs are not all of Romani origin, since the administrative category of “Gens du Voyage” was created in 1969 to arbitrarily group together all French people with an itinerant lifestyle.

References:

-

Cornwall, Andrea, 2008. “Unpacking Participation: models, meanings, practices”, in: Community Development Journal, Volume 43, Issue 3, July 2008, pp.269-283.

-

Janes, Robert R. and Richard Sandell, eds., 2019. Museum Activism,

-

McSweeney, Kayte and Jen Kavanagh, 2018. “The Power of Participation for Enriching Collections and Displays”, in: Spokes, no. 19. See: https://www.ecsite.eu/activities-and-services/resources/participation-and-co-creation

-

Sitzia, Emilie, 2018. “The Many Faces of Knowledge Production in Art Museums: An Exploration of Exhibition Strategies”, in: Muséologies. Les cahiers d’études supérieures, Volume 8, No. 2, pp.141-156.

[…] Next blog entry […]

[…] Previous blog entry […]