Thinking and Building through Roma Positionality

©Kale Amenge

Even as I sit to write this short piece, I seek to find my voice through writing. For me, as a Romani woman, writing has become one of those forms that have allowed me to tell the history of anti-Roma Europe: the unspoken history. The embedded European racial terror against Roma and other racialised people remains so invisible for many because the Roma body is seen and treated as non-human, or not human enough [1]; hence, the violence against us has become quite normalised, and/or justified. As a scholar on race, racism and the politics of anti-racism, as well as being an anti-racist militant, I have come to admire many scholars and political activists who built the foundations of these topics: those who argue about the importance of breaking up with the figure of the white man as a synonym of humanity; those who claimed liberation beyond inclusion into the state’s policies; and those whose resistance is based on dignity, respect, self-organisation and self-representation.

Nonetheless, during all these years I have also met with scholars and activists who rarely include the experiences of Roma into their analyses, those who still wonder if what Roma face is racism or not, if our oppression is a product of the colonial racial order or not. It took me many years to wonder and ask: can we really discuss and understand the history of European racial order without taking into consideration the racial persecution of the Roma, and their daily experience in anti-Roma Europe? Can we truly understand the history of European modernity without looking at the processes of the dehumanisation of the Roma? How is it possible to ignore the experiences of a people that exists in Europe for more than five centuries and who are the largest minority in Europe? Five hundred years of systemic oppression; yet, anti-Roma racism is not tackled as a political ideology built into the DNA of “civilised” Europe!

These questions are important to ask in order to understand the current situation of the Roma and why it has been made difficult for us as Roma to speak from the centre, and to create our processes of becoming[2] and existing. To be more precise, through writing I seek to find the Roma voice, that voice that colonial domination has taken away for centuries, while it made us believe that we do not have a voice to speak up. We have been taught that we do not have the voice to speak up because we are incapable of speaking for ourselves; thus, we can only be explained by those in power. Our knowledge is not legitimised, thus not acknowledged, because the knowledge produced by the colonised has no value, as they are less than human.[3] This is colonial ideology! I keep remembering Audre Lorde’s words:

And when we speak we are afraid

our words will not be heard

nor welcomed

but when we are silent

we are still afraid

So it is better to speak

remembering

we were never meant to survive.[4]

Of course, the important question was never whether the Roma can speak, but rather if the white[5] people can listen. Experience has shown that in white spaces (of domination), Roma people have been denied the privilege to speak. From academic to art spaces, white scholars, artists, etc., have constructed the Roma body as the ‘Other’ body placed in a permanent subordination. Precisely because of such power relations in between, speaking from the centre also means creating our own spaces, where we can speak for ourselves and be heard, and tell the untold history of anti-Roma Europe. Historically, we did not have our own institutions that would have allowed us to establish a process of becoming. I understand the process of becoming as what bell hooks has defined as the subjects, those “who have the right to define their own reality, establish their own identities, name their history.[6] In this quotation by hooks, I closely identify the Roma struggle, too: historically, as Roma people, our identities, culture, and realities were always defined and told by others, and our history, as hooks says, “history named only in ways that define (our) relationship to those who are subjects”.[7]

It is precisely within this context that writing, making art, playing music, teaching, or being a political activist, are in fact political processes that allow us to be the subjects instead of the permanent objects. This process, according to Grada Kilomba, is “an act of decolonisation in that one is opposing colonial positions by becoming the ‘valid’ and ‘legitimate’ writer, and reinventing oneself by naming a reality that was either misnamed or not named at all”.[8] The act of decolonisation is a necessary act because “there is still the necessity to become – to make oneself anew”.[9] And I am so very happy to have found my Roma fellows searching various ways for us to become the subjects and name our own realities and history: from the beautiful artistic work of my sister, Alina Serban, an award-winning Romanian Roma actress, playwright and director, who through the short film, “Letter of Forgiveness”,[10] told us the history of Roma slavery in Romania, a history of Europe mainly unknown to many of us; to Helios Gómez, the first Romani poet to write in Spanish and a communist activist who fought against Fascism and whose literature reveals his commitment against the struggle of persecution; to Helios F. Garces and Cayetano Fernandez, my fellow militants who have placed the anti-racist political fight into the Roma struggle and who have offered us a different perspective on the fight outside the integrationist logic; to Bronislawa Wajs, commonly known as “Papusza”, and her amazing poetic work in Romanes. And many more artists and activists, but most importantly, all those Roma who are forcibly placed to live in ghettos, while facing everyday systemic persecution for who they are; yet, they have never forgotten their Romanipen[11] – identity performativity is one of the most important political acts of resistance!

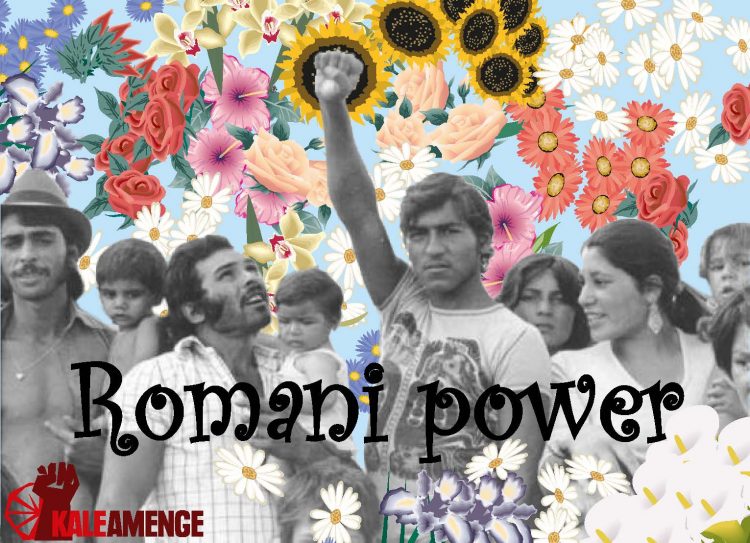

As alongside my militants in Kale Amenge,[12] an independent and autonomous anti-racist Roma political organisation that from a decolonial perspective works for the collective emancipation of Roma and the building of Roma political autonomy, have always highlighted that decolonising the racist and white supremacist system is not an option but a duty: we must decolonise the knowledge and practices created about us without us. Such processes are crucial for our development in becoming subjects, because as Cayetano Fernandez has pointed out:

“Anti-Gypsyism is a race-based system of domination that has historical roots in modernity and that obeys the construction of the European white man as the model of humanity, thus dehumanizing all others. As Roma, we are considered as not humans enough, therefore, we are denied this political capacity of self-determination and, at the same time, to close the circle, this serves as a justification for the implementation of an “ideology of integration” that seeks to “civilize” us within what they consider to be civilization. That is why, the battle against anti-Gypsyism cannot be limited to trying to change prejudices or certain misconceptions in the minds of the gadje, but to understand that this system of domination is rooted in the State itself and its institutions. In other words, the problem is not that there are racist teachers, police, judges or social workers, the problem is that the educational, judicial and prison systems, etc. are all built on the basis of anti-gypsyism. Anti-gypsyism is mainly state racism”.[13]

Taking as a point of departure this analysis provided by Cayetano Fernandez that antigypsyism is mainly state racism, fighting against means fighting against the system that creates and maintains it. Of course, we know this is the long-term aim of the fight; however, it is meanwhile crucial to start by decolonising our minds, knowledge, practices and strategies created about us, and to conceive of practices that would allow us on the one hand to be liberated from dependency upon the racist system; and on the other, would allow us to become the speaking subject.

Accordingly, my political opinion regarding the concept of RomaMoMA, a contemporary art project initiating a forum for collaborative reflection on a future Roma Museum of Contemporary Art, which asks whether we need a contemporary Roma art museum or not, is to answer: absolutely, yes! I say yes, because, as I have mentioned above, we cannot “fix” the already existing dominant institutions, precisely because they are meant to be the way they currently are: racist! Thus, we must create our own institutions. For me, the debate is less about whether we need it or not, but rather what type of institutions we need. We need institutions that, through their work, will be able to fight against anti-Roma racism. We need institutions that would create important content for our history and emancipation. Institutions that would allow space for decolonising the racist knowledge and practices against us. And especially, to fight against those non-Roma people who have used our struggle for their own benefit. Art work, as any other “work on Roma”, is never neutral when created by the dominant, because it always has political consequences on the lives of Roma.

We need independent institutions that would allow emancipatory projects to be developed.

We need institutions that would use Romanipen as a political tool against antigypsyism.

Institutions matter if they are properly used – for Roma collective visibility, narrating our history within anti-Roma Europe, creating projects that will be emancipatory for us and our future generations.

Most importantly, we need institutions that would represent the everyday resistance of our people so that they could feel identified in the work we do and fight against and for.

[…] Next Blog Post […]

[…] Previous Blog Entry […]