Reframing Restitution: The Case for a Roma MetaMuseum

Part of the Romany Life Centre Collection. Photo Daniel Baker

The evolving concept of a Roma Museum has a crucial role to play in reclaiming access to our cultural histories, but questions remain regarding its future form. Possibilities range from a mobile museum to a dedicated building, but while debate continues, perhaps a more oblique take on the subject—a Roma MetaMuseum—might move us closer toward achieving our goal of restitution. By sharing content across institutions, we create a multi-sited museum that annexes existing collections to bring together the vast wealth of our creative output under one umbrella organisation. Our history cannot be contained in a single museum.

Biographies of Objects

The links between personal archives and state collections, and between domestic artistic activity and contemporary art continue to be of interest to me as a theorist of Roma aesthetics, and also as an artist. These hierarchies of collecting and practice can otherwise be thought of as emblematic of the relationship between the marginal and the elite. By unpacking the often discriminatory connections between marginal artistic practices and those that form the centre ground, we can find new ways of thinking about relationships between marginalised peoples and mainstream society.

Focusing on the workings of art as a mechanism for understanding, and perhaps tackling discrimination, makes sense when one conceives the art object as a site where artist, subject and audience meet, and therefore where meaning is shaped and exchanged. Art objects generate a variety of meanings, each meaning dependent upon the context in which they are presented. Within this understanding of the functioning of art, the potential outcomes are manifold, as are the various roles that art objects perform. The fluid nature of the art object and its contingent meanings renders all the circumstances of its acquisition and representation of vital importance in our perception of it, and consequently our perception of its place in the world.

When an item is held in a chaotic environment yet made freely available for view, it will be valued in a particular way. When the same item is held in a carefully controlled space but kept under wraps, then it will be valued in a different way. The very same object’s capacity to transmit meaning and therefore the value that we place on it changes depending upon its provenance (or biography), and how it is represented—much like the life of a person.[1] This interchangeability of persons and things is congruent with the notion of culture industries (including the art world) as essentially biographical in nature, insomuch as they represent a series of accounts of the social relationships that occur across the lifespans of artworks. Such an approach allows for a localised account of the art object and its influence upon the social relations that surround it. It also highlights that the ways in which objects are cared for and circulated can impact their wider social and cultural connections.

At the heart of my practice is a preoccupation with the role of art in effecting change. One of the ways that art can effect change is by showing us the value in that which is overlooked. When we are encouraged to look again at objects and ideas that have become obscured, we are also encouraged to look again at the people who have generated them. In this way, the artwork acts as an extension of the artist, who in turn acts as an extension of their community. By re-evaluating such objects, we are motivated to re-assess their makers and therefore the cultures from which they emerge. This repositioning of artworks, people and communities 3is crucial in encouraging us to build futures in our own image, whilst at the same time allowing us to re-examine our collective past—and why the re-thinking and re-constellation of Roma art collections is now so important.

The Lives of Archives

During the course of my art practice and my research into Roma aesthetics, I have visited a number of collections of Roma material culture. Two in particular stand out for me: one privately owned, and one state owned. The Romany Life Centre is a personal collection established by Henry Stanford and situated in the English countryside of Kent. The seemingly chaotic appearance of the assembled objects belies the Romani[2] owner’s passion for the archive, each item of which carries the story of its manufacture and acquisition through Stanford himself. Alongside the smaller artefacts, the collection also includes a selection of vehicles and dwellings on its grounds. Due to the more recent nomadic history of Romani Gypsies in the UK, the concept of the art object in the traditional sense has been largely absent from British Romani cultural narratives. Consequently, we find in the Stanford collection a focus on décor and the ornamentation of the home, seen at its zenith in the English Gypsy vardo (Romani wagon or caravan). This British Gypsy approach to art-making and collecting contrasts some larger European Roma collections, where the concept of the art object has historically been more readily embraced by Roma and represented in their artistic output.

The Hungarian Museum of Ethnography in Budapest has a large collection with a strong focus on narrative painting in the Western art tradition. I visited in December of 2006 during a preliminary meeting in preparation for Paradise Lost: The First Roma Pavilion[3] at the Venice Biennale, along with other Roma artists and chaperoned by Paradise Lost curator, Tímea Junghaus. As the curator of Roma artefacts escorted us to view the collection, it soon became clear that the artworks in question were not to be found in the public galleries, but in a different part of the building. The extensive array of paintings that we had come to see were held in the basement, hung on the hinged racks of their storage facility. The collection was clearly held in high regard by the curator—and presumably by the museum, but no explanation was given for the lack of public access to it. The collection’s exclusion from the main body of the museum not only signalled its marginal status, but also compounded its outsiderness.

Roma Collection storage facility, Ethnographic Museum, Budapest. Photo: Daniel Baker

Each type of collection has its advantages and its disadvantages. For example, private collections are often highly specialised, showing personal enthusiasm for the subject and offering increased access to artefacts, and sometimes their makers. However, their precarious nature, along with a lack of expertise in display, conservation, archiving and documentation, can often mean that they are unstable both in condition and in permanence. Sadly, this is the case for The Romany Life Centre, which no longer exists as an accessible resource.[4] This means that the wealth of knowledge embodied in those objects is now lost to the world, both as a vehicle for celebrating our culture, and also as a site for learning.

For state collections, conservation takes priority, in order to maintain the condition of artefacts for the future. But often these items are inaccessible to the public, resulting in works of cultural importance being divorced from their origin, thus breaking the connections between the agency of those objects and the communities that have generated them. Permission to access, view, loan or reproduce artworks is solely at the whim of the museum – and rarely granted, in my experience. Often the objects in question have been freely donated to museums by artists or collectors, yet are treated as state booty, with all links to the people and communities from which they have emerged severed. This kind of appropriation of cultural capital is damaging not only to the connections between artefacts and communities, but also between institutions and their public. Maintaining links between communities and artefacts need not risk their safety. Conservation need not be a prison. Pooling expertise and enthusiasm across Roma collections would strengthen connections between currently fragmented archives and could result in a network that not only unifies, but also consolidates the wealth of Roma artistic production.

Artefacts as Action

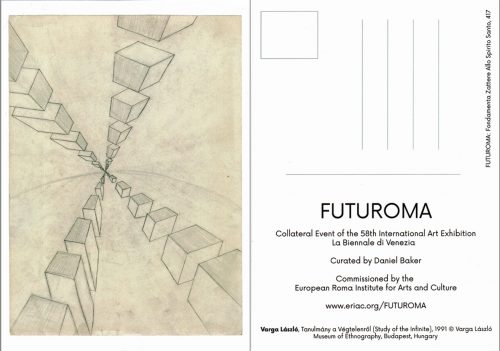

In 2019, I curated the FUTUROMA exhibition. The project was commissioned by the European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture as a collateral event of the International Art Exhibition at the Venice Biennale. A key artwork that underpinned my concept for the show was a drawing by the Hungarian Roma artist, László Varga, entitled Study of the Infinite. Varga’s intricate work places the idea of space and movement at its centre. The existential imperative of liberty is brought forward by offering the possibility of limitless freedom and infinite potential. Notions of liberation—and conversely the restrictions thereof—were highlighted through the inclusion of this artwork, whose actual presence could not be secured for display from the Museum of Ethnography in Budapest for a variety of reasons, some of which remain unclear. In place of Varga’s drawing, 1000 postcards were produced bearing its image for display and distribution, to highlight questions touched upon above regarding the liberation of Roma cultural capital and its implications for wider questions of Roma emancipation.

FUTUROMA postcard featuring artwork by László Varga. Photo: Daniel Baker

Art and life remain closely linked within Roma society, as is apparent in the way that community and domestic artistic practice have formed the foundation of what is now the international Romani art phenomenon. Resistance remains a recurring element across Roma art practice and the Roma aesthetic, producing artworks that operate as arbiters of visibility, recognition and equality. Many works combine visual and material signifiers to produce resistant objects, which at once occupy the realms of the domestic and the political. By interrupting the expectations of the viewer, these and objects like them enact resistance – not through overt political acts, but through subtler and perhaps more compelling means. The resulting outcomes can be pivotal in promoting dialogue across diverse groups, but the impact of those outcomes remains dependent upon the differing frameworks in which they are experienced; thus, the need for some control over the representation of our collective artistic output, both historic and contemporary, is so vital.

The evolving concept of a Roma Museum has a crucial role to play in ensuring access to, and the understanding of, our material histories – but questions remain regarding its future form. Possibilities range from a mobile museum to a dedicated building, with many potential variations in between. Any type of museum would be a great asset, but while debate continues, perhaps a more oblique take on the subject might move us closer toward achieving our goal. This would begin with the identification of existing works and their location through cooperation with relevant collections across the world. This kind of investigation has been carried out to great effect by the International Inventories Programme (IIP)[5], which has identified the location of over 32,000 Kenyan artworks held in overseas institutions to date. Identification is important, but experience tells us that museums that hold artefacts from other cultures are unlikely to part with them. The Parthenon Marbles at the British Museum are a case in point. In light of the proven and likely future intransigence of institutions to hand over artworks, restitution may be best served by encouraging institutions to share their collections with us.

The MetaMuseum

In sharing content across institutions, we create a multi-sited museum: one that annexes existing collections to bring together the vast wealth of our creative output under one umbrella body. A museum that exists across multiple sites simultaneously would reflect the multiplicities of the Roma experience and the consequent multivalency of the Roma aesthetic, as evidenced across our visual, material and performative culture. Museums that currently hold works by Roma could be encouraged to take part by the prospect of adding value to their collection, and at the same time enhancing their profile in terms of inclusivity and diversity – an attractive proposition, one would imagine, for many that now stand accused of discriminatory and colonialist collecting practices. Museums with no Roma works could be encouraged to acquire works by Roma and expand their exhibition programme to include Roma artists. Encouragement to share could become an alternative to accusatory standoffs and perhaps result in a more strategically positive outcome. A “Year of the Roma MetaMuseum” might even be set up to launch the initiative.

The initial audit of institutions would result in an organic inventory of Roma artworks and their location – a valuable asset in itself. Building on this groundwork, each institution would be invited to become part of the Roma MetaMuseum, which would exist alongside the participatory institutions, but also operate as a discrete entity. Each museum would still keep their holdings, but these would also become part of a more expansive and cohesive whole. The MetaMuseum would differ from initiatives like the RomArchive, in that as well as being a dynamic and developing resource, it would be complemented by a map of geographical destinations offering the possibility to tour the collections in person.

Through its capacity to accommodate both digital and physical research, the MetaMuseum could generate multiple outcomes and a variety of opportunities to engage with its contents, both virtually and in the flesh, thereby increasing the possibilities for us and others to consume and celebrate our treasures on our terms. The numerous lockdowns over the past eighteen months have taught us nothing if not that participation in the museum has changed forever. As difficult as it has been to adjust to new modes of engagement, the experience has forced us to embrace new ways of consuming and appreciating culture. The primal importance of the physical encounter with art will always remain, but the potential for new kinds of interaction can only enhance our experience and understanding of the wealth of materials that forms our distinct cultural legacy—one which cannot be contained in a single museum.

The artwork that I would nominate to be featured in any eventual Roma Museum is the Horse Peg Knife by Frank Smith from The Romany Life Centre collection. Used for carving wooden pegs, this hybrid object acts as a chimera: a marriage of the ornamental and the functional to eloquently embody Roma values and Roma lifestyle. This unique object is also emblematic of the bringing together of a diverse cross-section of Roma visual and material culture to create a unified whole in the future Roma Museum.

Frank Smith: Horse Peg Knife. Photo: Daniel Baker

[1] These are ideas are explored in depth in my PhD thesis, “Gypsy Visuality”, with reference to Alfred Gell’s Theory of the Art Nexus, available at https://researchonline.rca.ac.uk/431/

[2] Romany is the traditional spelling of the word, whilst Romani has generally been adopted in writing intended for an international audience.

[3] Paradise Lost, Venice Biennale, Palazzo Pisani Sta Marina (piano nobile), Calle delle Erbe, Cannaregio 6103, Italy, 10 June 2007 – 21 November 2007.

https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/publications/paradise-lost-first-roma-pavilion-venice-biennale

[4] The collection closed a number of years ago under circumstances of which I am not aware – the author.

[5] IIP is an international research and database project that investigates a corpus of Kenyan objects held in cultural institutions across the globe. See: https://www.inventoriesprogramme.org/about-iip

This project was first brought to my attention by Nanette Snoep, Director of the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum in Cologne, during the recent panel discussion entitled, “The Restitution of Romani Artworks and Artefacts”, as part of the CEU Romani Studies Program 2021.

[…] Previous Blog Entry […]

[…] a previous post on this blog, Dr Daniel Baker described the art object “as a site where artist, subject and audience meet, and […]