Presentation of Roma Culture and Identity in Theatre

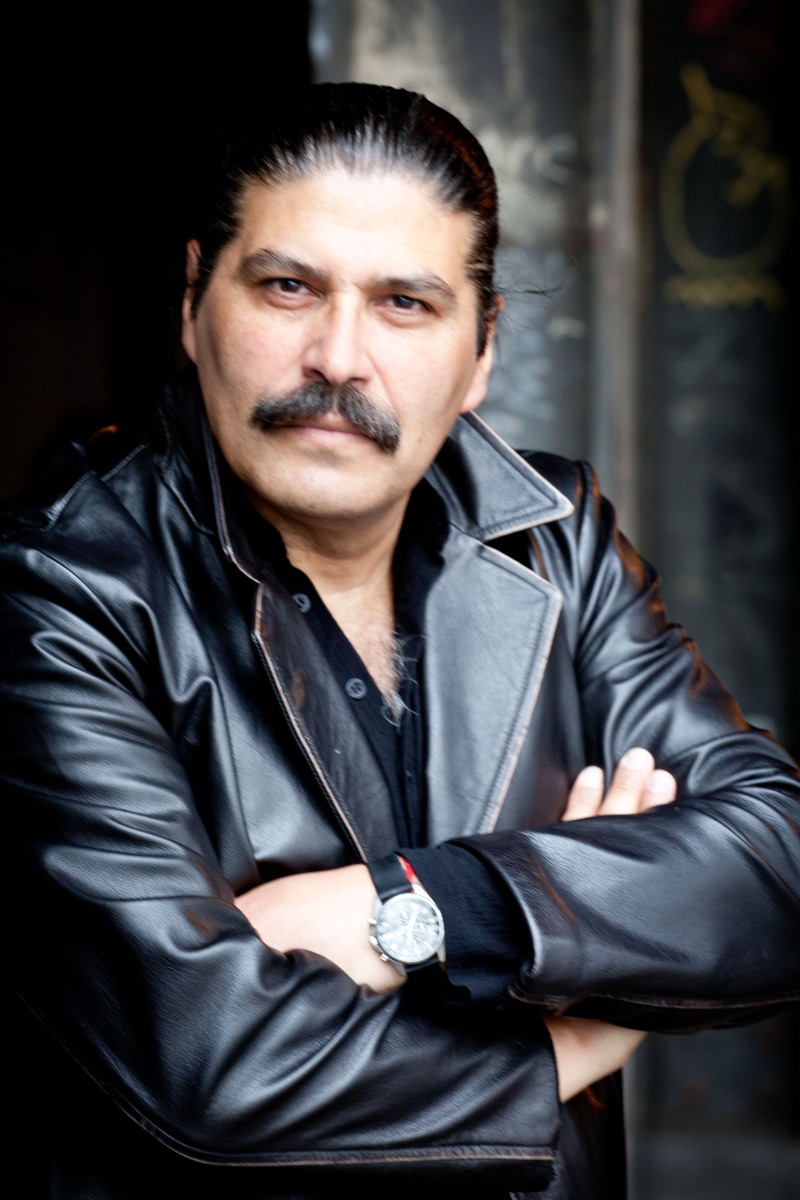

Nedjo Osman

There is no singular truth; this people, like any other, has its own history, tradition, and language, embodying a source of culture. It is precisely this source that constitutes an unfinished process of existence. The Roma serve as a prime example that identity is complementary and ever evolving, both on an individual and a collective level, enriching the essence of a nation through the perpetual process of existence. The Roma, by “spreading” their identity across Europe, have played a significant role in shaping Europe. Unfortunately, despite their cultural contributions, Roma creativity has often been overshadowed by discrimination.

Living without an address or surname, changing them every fifty or hundred years, starting anew in different cities and countries, sharing happiness before and after every war, while remaining true to life and fundamental human values—these are the central themes of Roma art. Despite enduring numerous persecutions and surviving significant destruction, the Roma have resisted and persisted. As they found themselves and started thinking long-term, Romani artists emerged—poets, painters, graphic artists, sculptors, theatre directors, and actors.

The power of Roma art, especially in recent times, is often misunderstood by both non-Roma and, even more unfortunately, also within the Roma community. Its presence continues to alter perceptions and images of the Roma people. Art, in a general sense, possesses the power to influence public opinion and shape the reality forming process. I am not thinking of cheap and exotic art, but rather the art of Picasso, the music of Paco de Lucia, Yul Brynner’s acting. At such moments, non-Roma might question, “What is this, and who are these people?”

Theatre, in the realm of culture and art, plays a significant role.

The establishment of theatres preceded the development of major European cities, emphasising the importance of language, literary analysis, history, tradition, and human formation within the theatrical realm. Like any art form, theatre reflects the spirit of its time, staying true to inherited ideas and traditions, while questioning and reacting to them.

Theatre delves into identity and collective truth, addressing humanity’s need to confront roots and dispel fears. Whether we choose to do so with a hammer or music, whether we navigate the darkness alone or together, is the question. Theatre possesses its own language, sometimes deeper than the written text, awakening the heart in those moments.

Romani theatre has a rich tradition, originating as street and court entertainment. One aspect worth highlighting is the Roma circus, renowned for its unique blend of dance and acrobatics, serving as inspiration for many subsequent circuses. In more recent times, the Moscow theatre deserves special mention. Emerging as a theatrical musical group in the 19th century, it was founded by conductor Nikolay Shishkin. In 1931,the Theatre Studio was established under the name INDOROMEN, later ROMEN. Primarily focusing on musical and dance genres, their main directors were Moishe Goldblat and Semen Bugachevsky. Apart from this theatre in Russia, there were also theatre groups in Hungary, the Czech Republic, Bulgaria, and Romania.

If we delve into the realm of classical theatrical forms, it is essential to mention the only Roma theatre that has made its mark on the professional European stage: Roma Theatre Phralipe from Skopje, North Macedonia.

The Tale of Roma Theatre Phralipe

The narrative of this theatre can serve future generations and theatre enthusiasts, shedding light on the success of this remarkable institution. Unfortunately, some have written about this theatre without truly understanding its history and purpose. I had the fortune of being a member and lead actor of this theatre for years, and so I can provide a more in-depth look into the Tale of Theatre Phralipe, hoping to inspire young actors and artists, while revealing the path to its success.

Stories about the Roma are particularly intriguing and unusual, as they transform the impossible into the possible, becoming fairy tales. Sadly, these fairy tales do not always have a happy ending due to their uniqueness, impossibility, fascination, and unpredictability. In one country, even the impoverished had the right to attend schools, work in factories, and live in cities; yet, despite these advantages, they did not enjoy equality with the majority: these were the Roma in the land of Yugoslavia.

In Yugoslavia, in 1970, a small Romani theatre was born. It emerged in one of the largest Romani communities in Europe, Šuto Orizare, also known as Šutka, on the outskirts of Skopje. This theatre was composed of a group of young Romani enthusiasts—several actors and their first and last director, Rahim Burhan.

At that time, no one foresaw that this theatre would one day be the subject of discussion throughout Europe, renowned as a classic Romani theatre. These young Romani enthusiasts, guided by their director Rahim Burhan, embarked on a new and different journey to explain Romani art and life — to showcase a new approach in the fight against discrimination and to find a new path for the affirmation of Roma culture, identity, and language. Little was known about them among the non-Roma; their existence was primarily perceived through clichés and stereotypes. How could they convince others that theatre could affirm Romani culture? Initially, it was crucial to establish the style and form of the theatre, its face, and its language.

Rahim Burhan, through Theatre Phralipe, developed a distinctive form—physical and ritualistic theatre. He drew inspiration from the works and theatrical aesthetics of French actor, director, and theatre theorist, Antonin Artaud, as well as Polish director and theatre theorist, Jerzy Grotowski, along with Indian performance forms like Kathakali.

The theatre’s first production in 1971 was No, No, a play against the Vietnam War. In 1973, Mautije, a play about the Goddess of the Violin. In 1975, “Soske” (Why), a play addressing national socialism and Romani victims of the Holocaust.

The Romani Theatre Phralipe engaged in ritualism, incorporating movement, screams, and other sounds into its performances. It explored humanity, delving into identity—a theatre placing emotions and energy at the forefront, where everything was real. During that time, it primarily functioned as non-verbal theatre due to language barriers, focusing on Romani themes, traditions, and rituals in a more classical manner. Word of Phralipe’s theatre spread among young Roma, sparking a growing interest in acting and theatre. Young Roma would come and go, but those who understood the purpose stayed until the end, including Rejan Saban-Sulc, Umer Djemail, Sami Osman, Skender Ramo, Saban Bajram, Salija Salih, Muharem Jonuz, and others.

The theatre made its mark on the Yugoslav stage with the play Soske, leading to invitations to participate in major Yugoslav festivals that typically hosted only professional Yugoslav theatres. Phralipe won the Yugoslav audience and theatre critics’ awards, receiving coverage in the most significant Yugoslav magazines, about the theatre that speaks in some language no one understands, conquering with emotion, energy, and its unique artistic style.

In 1977, Theatre Phralipe was invited to the legendary French theatre festival in Nancy and participated in numerous other European festivals, as well as all the major theatre festivals in former Yugoslavia.

In the late 1980s, Phralipe transitioned to verbal theatre while retaining its distinctive style of performance. It started adapting well-known dramatic texts, from Greek tragedies and Shakespeare to Yugoslav playwrights. In 1982, the play King Oedipus by Sophocles achieved significant success, leading Phralipe to perform at the Delfi Theatre Festival in Greece. A new generation of young Romani actors, including Baki Hasan, Ruis Kadirova, and myself, brought a fresh perspective to the ensemble during that time.

Theatre Phralipe included plays like King Oedipus, People and Pigeons, Non-Smokers, Infinite Question, Theban Tragedy, Mara Sade, Jegupka, Oresteia, and others in its repertoire. Performances, festivals, and tours continued in both Yugoslavia and Europe.

In 1990, conversations began with theatre director Roberto Ciulli from Theatre an der Ruhr (Mülheim). In the fall of 1991, with the support of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the Ministry of Urban Development, Culture, and Sport, Theatre Phralipe was invited to become a permanent and independent theatre ensemble within Theatre an der Ruhr.

The year 1991 marked the first co-production, Bluthochzeit (Blood Wedding), based on Federico García Lorca’s text. Theatre Phralipe renewed its ensemble, welcoming non-Romani guest actors from Macedonia and Serbia for the first time. During that time, Ruis Kadirova and myself made our first appearance as academic actors in the Pralipe theatre, bringing another new dimension to the theatre’s work and professionalism. The production of Bluthochzeit, premiered in Mülheim in January 1991, and enjoyed sensational success, performed nearly 400 times throughout Germany and Europe over the years. Phralipe’s success in Germany during those initial years was unprecedented, especially for a foreign theatre.

This new theatre, with its unfamiliar theatrical language, became a German cultural phenomenon. Theatre Phralipe aimed to offer theatre while simultaneously introducing the audience to Roma culture and language. During those years, Roma theatre played the role of ambassadors in Germany, especially with the “Culture Against Violence” tour in 1992. Phralipe performed a series of plays in German cities, expressing opposition to the escalating hostility towards foreigners after attacks in Hoyerswerda and Solingen. This was a political agitation series using theatre against unprecedented hatred and still ill-defined right-wing violence against foreigners in Germany. During this tour, Phralipe had daily police escorts, a symbol of solidarity with the unwanted and the enemy. Phralipe was a theatre that, with its appearance and critically acclaimed plays performed exclusively in Romani, triggered an avalanche of success, unprecedented media presence, unmatched interest, and euphoria.

In those years, premieres like Blood Wedding, Othello, Romeo and Juliet, Great Water, Seven Against You took place, with tours across almost all German cities and major European festivals. Due to these successes, Phralipe received the German Critics’ Award for the Best Theatre in Germany in 1992, and in 1994, it was honoured with the Ruhr Award for Art and Science, along with numerous other awards and exceptional reviews in Germany and abroad.

My story with Romani Theatre Phralipe started as a “fairy tale” due to its uniqueness, impossibility, fascination — and a sad ending. It concluded in 1996 with the departure of some theatre members. Later, due to new arrivals motivated by personal interests, tensions arose.

In 2002, the work and existence of Theatre Phralipe came to an end.

I understood that Phralipe and Romani theatre should not have an end, but something else, something new. In 1996, in the city of Unna in North Rhine-Westphalia, together with director Nada Kokotovic, I founded our theatre, Theatre TKO, which later moved to Cologne and continues to this day. Theatre TKO is one of the few professional Romani theatres that have been a part of the German theatre scene for years. Theatre TKO focuses on Romani themes and experiments with well-known themes from real life, current issues, different nationalities and languages. These are visualised and presented in multicultural forms. Nada Kokotovic, one of the pioneers of the term “Choreodrama” in Yugoslavia, introduced this form to the theatre scene. Choreodrama incorporates elements of movement, acting, dance, and text—a form that, in my belief, most closely aligns with and suits Romani theatre and is the closest to what Phralipe Theatre was nurturing for years.

Upon leaving in 1996 and concluding my journey with Theatre Phralipe, I recognised that being an actor, being an artist, is not just a role played on stage: it is a role that accompanies you through life, presenting a task. Through your experience, professionalism, and commitment, you have the power to change others, especially young generations. Art is part of our development: it changes our lives, beautifies reality, and provides strength for something new. How many emotions can a song, play, film, painting, story, movement, or composition evoke within us? Each of these contents, in its own way, affects us; we absorb each one.

Art that explores Romani identity, literature, tradition, language, and history has the power, through creativity and means, to transform Romani culture towards a better future. The power of art can contribute the most to the fight against discrimination and change the perception of Roma among non-Roma.

Leave a Reply