Mucem’s Romani collections: bringing old collections up-to-date

Gabi Jimenez, Caravanes sous les Cyprès, 2001, inv.2021.15.1©Marianne Kuhn/Mucem

An interview with: Françoise Dallemagne, in charge of Collections and Research, Mucem, Julia Ferloni, head of « Commerce, Industry, Artisanship” collections, Mucem, Alina Maggiore, PhD candidate, Mucem/Aix-Marseille University/Freiburg University.

RomaMoMA: In 2017, the Museum of Civilizations of Europe and the Mediterranean (Mucem) has launched a co-curated exhibition project with ERIAC on Roma history, self-representation and fight against antigypsyism in Europe. « Barvalo » will be displayed in Marseille, France, from May 9 through September 4 2023. Could you tell us about the collaborative process Mucem engaged with Romani and non-Romani representatives?

Julia: A team of nineteen people of Romani (Rom, Sinti, Manoush, Gitan, and French Travellers who prefer being called Travellers/Voyageurs) and non-Romani origins, of different nationalities and socio-cultural profiles, has developed the exhibition collaboratively, being involved in all aspects of the project: elaborating the synopsis, choosing objects and items for its circuit, carrying out field research for the collated-surveys, creating the catalogue and selecting the cultural program and events held during the opening period of the exhibition. For our collaborative methodology, we drew inspiration from (Romani-authored) scientific, political, and cultural work around the representation of Roma in museums and cultural venues, and more specifically from „good practices“ who paved the way and experimented before us: the pioneering Museum of Romani Culture in Brno, Czech Republic, or exhibitions such as „Romane Thana“, staged at the Wien Museum and further travelled through Austria between 2015 and 2017 (Maggiore 2018).

Alina: The exhibition provides an opportunity for the museum to revisit its old collections on Roma in the context of a larger project with the aim to reindex holdings related to the representation of the “Other”. These collections where constituted in the past century following different methodologies – from targeted fieldwork to occasional acquisitions. Bearing in mind the exhibition’s scope and ethical mission, namely “ensur[ing] the portrayal of Roma as protagonists, agents of change and contributors to mainstream cultures and societies [,…] and also that Roma are not portrayed solely as victims.”, as stated in its ethical guidelines 2019, the “Barvalo” team has critically examined existing objects in collections. They found that the latter predominantly paint a picture of Roma populations that is rejected today by many of their representatives. Out of this reason Mucem has decided to bring the collections up-to-date, by simultaneously making new acquisitions and reindexing old holdings. All of these long-term activities are carried out in direct involvement of “Barvalo”’s experts.

RomaMoMA: You mention collections constituted a century ago. What is the history of Mucem’s Romani collections?

Françoise: As a ‘society museum’, Mucem holds few items belonging to the category of fine arts. The majority of the identified objects are popular art: utilitarian objects of relatively low material worth, used in everyday life. The ethnographer and museologist Georges-Henri Rivière founded the Musée des Arts et Traditions Populaires (MNATP, Museum of Popular Art and Traditions) in 1937, an institution of which Mucem is the direct heir. MNATP’s collections, before being transferred to Mucem in 2005 where their scope were widened to include European and Mediterranean civilizations from prehistory to today, focused on rural and, from the 18th century onwards, urban France. This collection also inherited the items from the ancient Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadero (MET) which opened in Paris in 1878 and closed in 1935.

Julia: From the 1960s on, Rivière constituted a collection on Roma cultures, by involving academic researchers in the project. André Malraux, the Minister of Cultural Affairs at the time, had a strong interest in the subject – which might have influenced Rivière’s choice. In fact, a letter Malraux sent to the society Etudes Tsiganes in 1964, in which he calls for the creation of “a museum of all that concerns Gypsies” (About 2021:3) testifies to this hypothesis. It is therefore not surprising that, Philippe Lemaire de Marne, a researcher specialized in Romani studies, was located at the MNAPT, an unprecedented research facility and museum (Bajet, 2021). This occurred upon the creation of the Centre d’ethnologie française, stipulated by a convention between the Centre National de Recherche Scientifique and the French Museum Directorate in 1966.

At the same time, the MNATP continued acquiring objects and popular imagery representing “Gypsies”, however not in a conscious way: the museum didn’t intend to enrich its holdings focusing particularly on the representation of Roma groups. Rather, the occasion presented itself to add sets of items to collections containing elements linked to Roma: upon buying sets of advertising cards, or transferring vinyl records and partitions from the collections of the Musée de la Chanson …

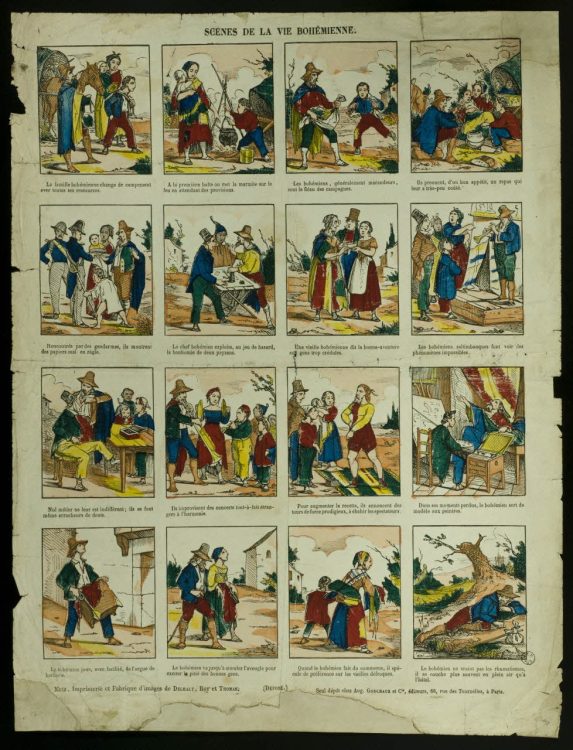

Alina: All of these objects demonstrate the stigmatizing way in which French people saw Roma in the 18th century: in a particularly stigmatizing way including the recurrent stereotypes of thief, nomad, musician, free man, femme fatale, and children in rags. (Ill.1)

Françoise: This collection has been strengthened at the moment of Mucem’s creation by the repository of 33.000 objects of the Musée de l’Homme, originating from the collections of European anthropologists carried out in the 20th century. Therein, 89 objects concerning Roma groups were identified, coming mainly from Eastern Europe: Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, Hungary, Poland, Russia, Greece, Albania and Ukraine, but also Spain (Danet, 2021). Some where created or used by Roma, or Gitanos. Others are telling of racist practices of dominant societies, to a more or less advanced degree: ethnic „type“ statuettes, carnival costumes… (ill. 2). Today, more than 900 objects referring to or connected with Romani populations are listed in Mucem’s inventory.

Scenes of Bohemian life, print, 1850-75, inv.1953.86.4128 ©Mucem

RomaMoMA: Was it difficult to identifying those collections as Romani?

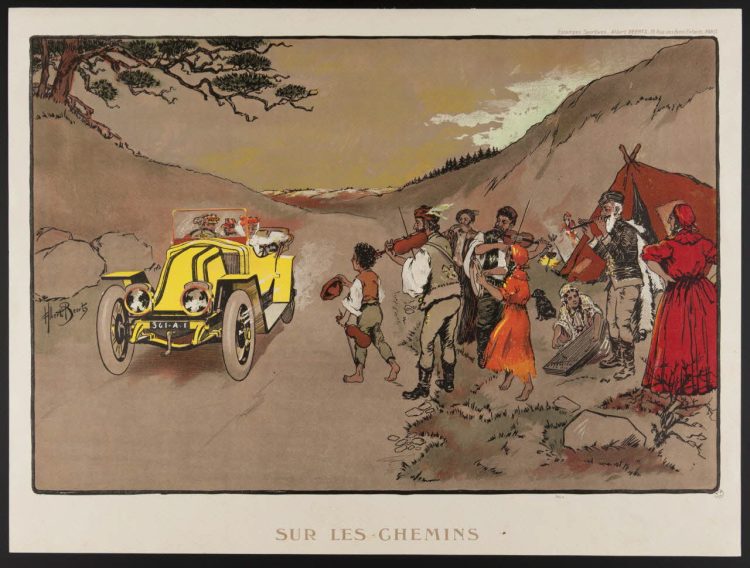

Julia: The number of objects related to Roma is constantly growing due to ongoing research and the fact that the categories according to which an inventory has been established vary. In fact, it was detected that Roma heritage is ill-indexed. For example, objects are not associated correctly with the right groups. This becomes clear as the titles given to objects contrast with the additional information provided by researchers, collectors, and/or archivists, as we can see in the example of the print “On the Road” (ill.3). The keywords provided define the group as ‘Gitan’, while no element distinguishes them from other Roma groups apart from the fact that their displayed characteristics would generally be identified as itinerant, and by doing so, wrongly attributed to a presumed comprehensive ‘Roma identity’. Another keyword added, ‘begging’ (mendicité) associates the activity of music playing, which Roma have been exerting for centuries on a large variety of levels of virtuosity, with a persisting stereotype. Following Modest and Lelijveld (2018) we argue that correcting these keywords and contextualizing their usage in the informational text is of considerable importance to overcome stereotypical representations as manifestations of the way that Roma populations were considered, perceived, and treated at the moment of the collection of these objects, as well as of their indexation. In order to critically reflect the museum’s own practices, the sensibility, expertise, and knowledge of the Roma group is central to this ongoing project of indexing the collections and of collecting.

Françoise: Re-indexing is not about removing originally introduced information, especially because heritage law in France prohibits it – though it does accept modifications and complementary information. We focus particularly on the information provided on the online collections database, for example by introducing new titles distinguishing between the „applied title“ used today and „original titles“ deemed racist or hurtful. In the same way, we add comments to the items which contextualize and help understand in which way the representations are stigmatizing. Lastly, we document the reindexation, specifying that our work is one of re-reading, inscribed in a precise place and moment of history, in the same way that the first indexation of objects provided a dated interpretation, which is regarded as questionable in 2022.

Alina: The Barvalo experts were consulted regarding an important point. How should we rename those groups that in our collections are called, in the best of cases, „Gypsies“? A conceptual seminar in January 2021 in the context of the exhibition preparation was dedicated entirely to this delicate topic: it is not easy to find a common appellation that satisfies all of the groups which are usually amalgamated among an exonym. A consensus was reached and the term „Roma“ in English, and „Romani populations/groups“ in French were chosen. These are the terms that will appear from now on in the online database of collections.

Julia: Working on the reindexation of more than 900 objects takes some time. This work will be completed in the course of several years.

Sur les Chemins, print, 1906, inv. 1963.5.52 ©Mucem

RomaMoMA: The assessment of Mucem’s collections suggests a lack of self-representing objects that were created or used by individuals belonging to Roma groups, as well as a lack of objects that represent realities of present-day Roma and reference contemporary issues and struggles they face as individuals and collectives. How did you challenge this partial heritage?

Alina: Here, we stress the need to differentiate between different groups and their respective ideas and needs in terms of representation. This question was addressed in different circumstances during the joint elaboration of the items list for the exhibition: upon adding ideas and comments to the list so far, during discussions held on the occasion of conceptual webinars in plenary, and interviews scheduled to discuss individually. Originally, all of these moments of exchange were meant to be held in one dedicated live seminar in Marseille, which was prevented by the global pandemic. Out of this reason, this reflection is based on fragmented impressions and exchanges. What is most fundamental about them, is that being a diverse group passionate for discussions, the views expressed are far from being consensual. This is due to the initial configuration of the project, meaning the presence of representatives from different groups, countries and contexts – by no means a disadvantage. Instead, we benefit from this diversity to assemble a sample of a contrasted Romani heritage revealing the heterogeneity of groups which compose it.

One of the suggestions that might seem surprising, is that in the context of these exchanges, different elements have been discussed which recall the imageries and projections of non-Roma: values such as family, artistic domains such as music, and a material element seen as shared by some experts, the caravan and its polysemic potential. In fact, it is argued that on the hand, its symbolism is a central component and a prism of the complexities of French Traveler identities and the assertion of rights linked to it. On the other, it is also more widely recognized and acknowledged by Roma beyond the French frontiers due to its connection to the idea of freedom, which by some experts is perceived as commonly shared among different groups. What’s more, others see the caravan as embodying a common sensibility towards its aesthetics and design as an habitat shared by different groups. With the aim of meeting this demand, which was mainly expressed by French experts, it was decided to acquire objects from a caravan, since a whole wagon would have posed storage problems. With the proper documentation and contextualization through photographies taken by an artist in close cooperation with French Travelers, these objects speak of and highlight the aesthetics of the Traveler habitat.

A mask from Romanian popular carnival, inv.DMH1992.43.12.4 ©Mucem

Julia: The Barvalo experts also suggested fieldwork areas and the collection of objects dealing with the topic of Romani professions and know-how in Europe and the Mediterranean, the initial subject of the exhibition. If the experts wished to do so, they have realized collated surveys themselves in collaboration with anthropologists if they lacked training in the scientific discipline. To ethically frame this collecting, we edited special guidelines (Ferloni & Olmedo, 2019). It is thanks to them that objects, photographs, filmed and recorded interviews, and documentaries now enrich Mucem’s collections. Today, eleven collated-surveys in France, Spain, Romania, Hungary, Great-Britain, and Turkey were carried out, on professions ranging from applied art, politics, music, and medicine. A last one about Voyageurs markets in France, focusing on Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer’s pilgrimage market, will be launched in 2023. Small and middle-scale companies were explored through portraits of Romani professionals.

Françoise: The experts also stressed that the inclusion of Romani contemporary art is particularly relevant. One expert stated that art created by Roma artists should be privileged as opposed to that of non-Roma artists who might act with ‘good intentions’. In fact, Roma artists’ ability of establishing a certain level of intimacy, of speaking from personal experience and context is highly valued by some experts. Accordingly, artwork by Ceija Stojka, Damian Le Bas, Delaine Le Bas, Gabi Jimenez (ill.4), Rosa Taikon, Marina Rosselle, Valérie Leray, Nihad Nino Pušija, Marcin Tas or Malgorzata Mirga-Tas has already joined or is currently in the acquisition process for Mucem’s collections. While some of them like to highlight that they refuse the simplistic label or ethnographic category of “Roma artist”, these artists weave antiracist stances in their work and seek to convey universal messages.

Alina: In our experts’ view, some of them encapsulate different dimensions of Roma history and of the societies in which they live, as for example Ceija Stojka. Her work is seen by some of them as representative of a moment of rupture: the Second World War and the deportation of almost half a million Roma in internment and deportation camps, but also the resilience and agency of Roma in the context of their persecutions, and beyond. The experts argue that transcending the historical dimension, Roma identities are expressed in these artists’ work through its rootedness in the community, and the underscoring of Roma cultures and experiences.

Françoise: In the eyes of Mucem, it is of paramount importance to include these artists and activists in collections. Many of them reappropriate stereotypical images, identical to those already present in the earlier holdings of the museum, coining a perspective on their own culture and its modes of representation. At the same time, their work presents an occasion for the institution to update its understanding of these objects – for some of them, more than a century after having entered the museum. These abundantly talented artists re-read them critically and with legitimacy. Finally, these holdings, acquired in collaboration with specialized researchers and representatives of different Romani groups, have now become part of French national heritage through Mucem’s collections.[1]

References

About, Ilsen (2021) « Un musée imaginaire des mondes romani et voyageurs en France », Hommes et Migrations, 2021/3 (n. 1334), p. 91—101

Bajet, Félicie (2021), Philippe Lemaire de Marne, un cœur discret entre les mondes gazo et romani, Mémoire de Master 2, Ecole du Louvre, [Unpublished document]

Danet, Emma (2021), Le patrimoine romani au sein de la collection Europe du Musée de l’Homme en dépôt au Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée, Mémoire de Master 2, Ecole du Louvre, Paris, [Unpublished document]

Ferloni, Julia (2020) « Barvalo. Designing an Exhibition and with Roma communities in a French National Museum » on the RomaMoMa blog.

Ferloni, Julia & Olmedo Elise (2019), Guide de l’enquête-collecte “Métiers et savoir-faire romani en Europe et Méditerranée”, [Unpublished document]

Maggiore, Alina (2018) Exhibitions as a tool for self-representation by and for Roma, Mémoire de Master 2, Université de Venise, Montpellier, Strasbourg, et Barcelone, [Unpublished document]

Modest, Wayne & Lelijveld, Robin ed. (2018). Words Matter, Work in Progress I. National Museum of World Cultures

[1] These objects will thus receive a status of inalienability, imprescriptibility and intangibility according to French law, n. 2002-5, 4th January 2002, concerning French national museums.

Next Blog Entry

Leave a Reply