Interpretations of Identity in Visual Art: Hungarian Roma Fine Art

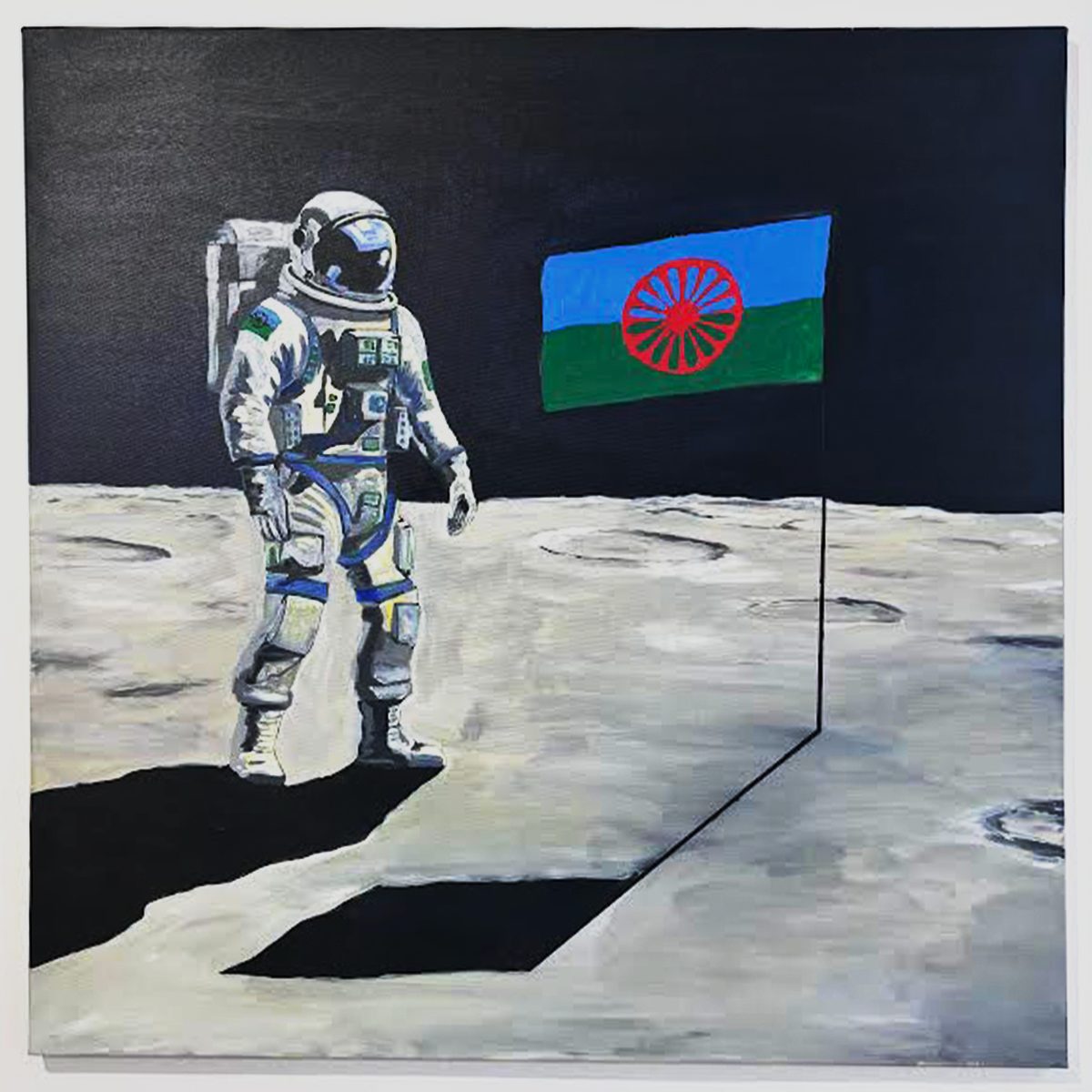

Norbert Oláh, First Roma Couple on Mars, 2024, oil on canvas, 100 cm x 100 cm

This paper seeks to explore the interaction between Roma identity and creative mechanisms, examining whether there is an ethnically defined form of art. It investigates the relevance of the concepts of belonging and the impact of a Roma artist’s social environment in the interpretation and reception of their artwork. By discussing the correlation between minority belonging and the creative process, I aim to uncover the nuanced, objective correlations revealed by the artists themselves. As such, touching upon some identity theories is warranted.

On Identity Theories in General

There are various identity theories, but there is no clear consensus on a unified definition, as different fields – such as social psychology, developmental psychology, clinical studies, etc. – approach it from different perspectives. This paper is also based on personal interviews that offer insights from an internal perspective, focusing on the artists themselves as the point of departure. From this human-centred, inward focus, I draw scientific conclusions, thus approaching the concept of identity as a sociopsychological process that occurs within an individual. The Latin-derived term refers to self-identity, self-awareness, and a sense of belonging, which encompasses the complex totality of characteristics that permeate our entire being and constitutes the essence of our personality.

The classical concept of identity was introduced by developmental psychologist Erik H. Erikson [1] (1902-1994) in 1950. In his intrapsychic theory, identity is indicated as a construct occurring within an individual as part of their psychosocial development. The beginning of identity formation can be observed during one stage of socialization, specifically in the 5th phase of his developmental theory: adolescence (roughly between 12-18 years), and it is completed by the end of this phase (18-22 years). Through individual life experiences and integrative processes, following the resolution of developmental tasks, an individual’s development can be traced, which undergoes continuous change.

Erikson formulates his theory as follows:

“The theory of identity is a process of social embedding, occurring in life cycles, crises, and the overcoming of these”.[2]

Although I approach the concept of identity as a sociopsychological phenomenon occurring within the individual, its formation and the socialization process are influenced by all external impulses, such as societal norms and regulatory systems, and the completeness of the various roles in different life stages. During these stages, interactions and interactive mediations between the individual and the community are articulated.[3]

The Barthian Concept of Ethnic Identity

According to the Barthian concept[4] of ethnic identity, attributed to Fredrik Barth[5], its formation and shaping occur through various social situations and transactions. These transcend the apparent boundaries of a specific ethnicity, establishing free mobility across ethnic borders, and overcoming the cultural constraints and limitations of a given ethnic group.

In addition to the numerous external factors influencing the individual, both Erikson and Barth suggest that personal expressions and transactions and interactions originating in the individual are the determining impulses that shape the environment. These can have a societal influence, even surpassing ethnic boundaries. However, within the context of these internally originating influences, the impact is especially amplified in the case of an artist, once the power of artistic creation, the ability to create value, and the freedom that transcends boundaries enter the picture.

The Complex Set of Erikson’s Theory of Identity

In the complex set of Erikson’s theory of identity, our gender identity, national consciousness, ethnicity, cultural characteristics, customs, beliefs, religious life, politics, education, professional knowledge, daily work, family status and roles, community belonging, value systems, intelligence types[6] and their development levels, our worldview, and way of thinking—all the factors that shape and define us—act as ethnic markers. These continuously evolve throughout different stages of life, with varying roles and age-related characteristics.[7] Of all the elements of identity and the wide-ranging societal roles, the Roma ethnic identity is merely one component of this complex sense of self, according to Erikson’s theory. It is only one specific element, among many others, that shapes the overall identity, just as other dominant aspects of identity remain equally important. Thus, singling out one element from this complex set does not fully represent the entire essence of self-identity or the true expression and interpretation of artistic fulfilment.

The Pervasive[8] Role of Roma Identity

It happens that the Roma sense of identity, due to its pervasive role, affects the experience of all other roles, making minority belonging strongly influence the overall identity—the complex whole of the personality. This has a decisive impact on the artist’s artistic philosophy and shapes their creative work. The pervasive role of Roma identity is particularly evident in Roma visual artists, some of whom proudly define themselves as Roma painters. Their minority background has a profound influence on their entire being, on the essence of their expression. However, even in these cases, other elements of identity emerge, in addition to the minority affiliation, such as childhood memories, the role of motherhood, religious life and faith, customs, and the world of stories and folklore.

Thus, more nuanced correlations between identity and artistic self-expression can be identified. The sensitive dimensions beyond Roma origin are reflected in their works, revealing a broader spectrum of identity’s complexity.

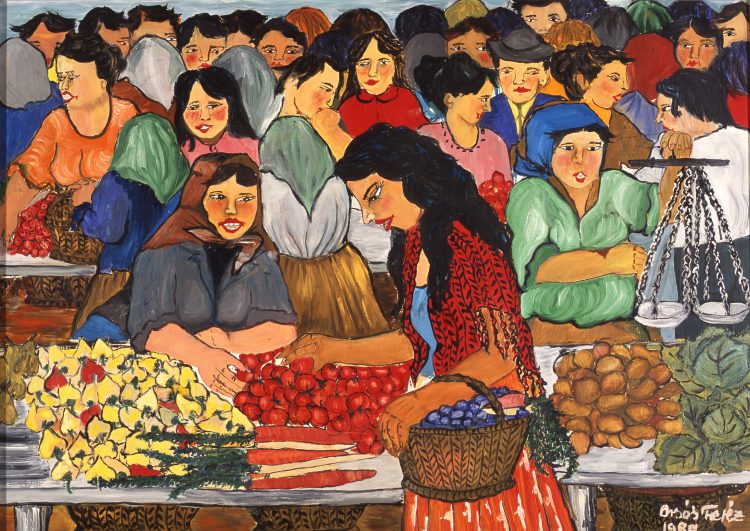

Teréz Orsós, Piacon (At the Market), oil on wood fiberboard, (OT/3), 50×70 cm. Courtesy of Romano Kher Roma Cultural Center Budapest.

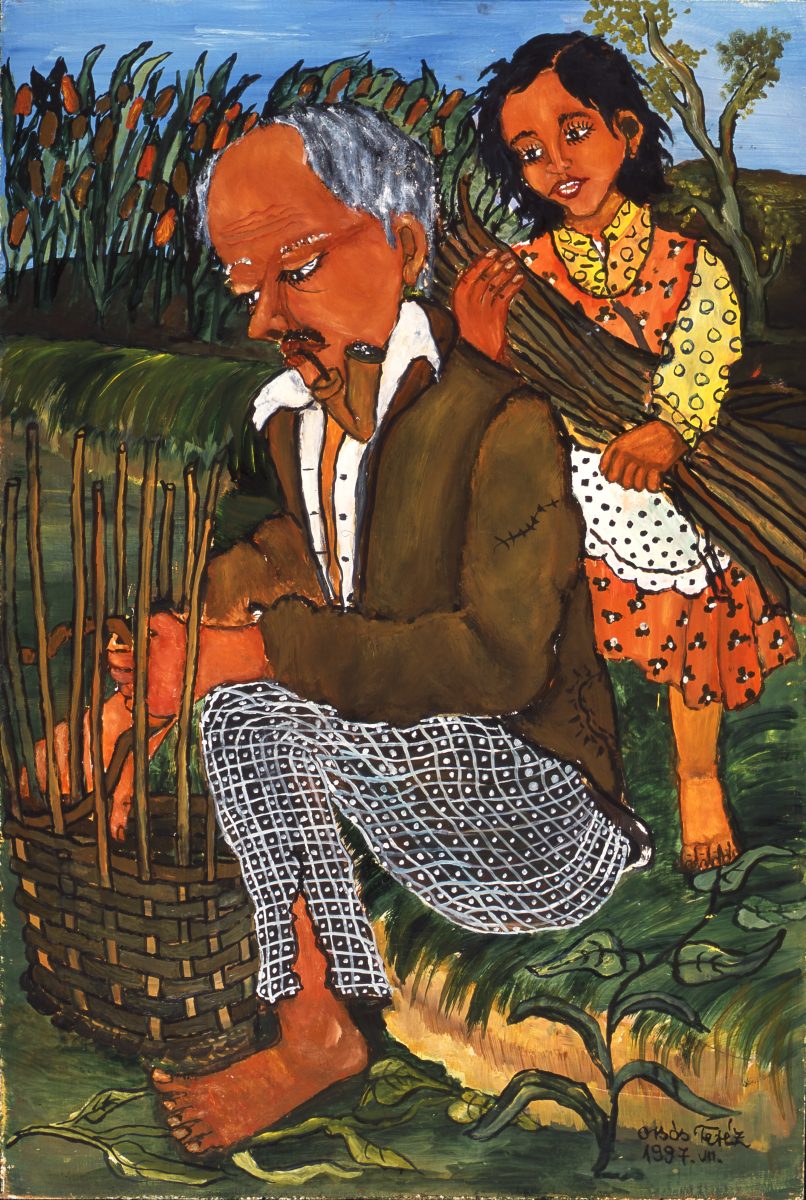

Teréz Orsós, Kosárfonó (Basket Weaver), oil on wood fiberboard, (OT/5), 60×40 cm. Courtesy of Romano Kher Roma Cultural Center Budapest.

The Intersection of Minority Identity Theory of Roma Ethnicity and Art

The minority identity theory of Roma ethnicity and its intersection with art is, therefore, difficult to grasp and articulate in a general sense. Depending on the creative attitude, the pervasive role highlights another important element of the artist’s identity, communicating from various aspects of other essential parts of their complex identity set. This could include the artist’s overall vocation and mindset, deep religious conviction, the experience of gender roles, the role within the family and related memories, political opinions, social critique, etc. – thus, a greater emphasis is placed on the entirety of the individual’s personality. Alongside the diverse, pervasive highlighting of identity elements, the context of artistic freedom uniquely influences creative mechanisms. The regions of art open up free-flowing inspiration for the creator, offering the liberty to draw from various sources. Whether it is impressions, experiences, mood impressions, complex abstractions, or raw instinctiveness, these all shape visual expression. Each artwork’s creation is often inspired by a distinct internal creative motivation linked to different identity markers. Therefore, it is worthwhile to approach each artwork individually for a more objective understanding and reception.

Márta Bada, Vizitündér (Water Fairy), oil on wood fiberboard (BM/6), 80×80 cm. Courtesy of Romano Kher Roma Cultural Center Budapest.

Based on all of this, the complexity of defining identity means that highlighting minority belonging, such as the term “Roma painter”, represents only one segment of the artist’s identity in the context of artistic reception and interpretation. Therefore, it is essential to consider and respect the segments of the creator’s identity that they themselves deem important. Contemporary professional painters, who are attempting to define their place in the art scene with an awareness of their self-identity, are the primary liberators of artistic identity today. The way an artwork is evaluated and received largely depends on the artist’s personal motivations. The emotional and intellectual message of the artist is the primary determinant and inspiration for the creation of a work and its message. The expression of their individual and momentary feelings and thoughts determines the birth of the work. The identity element that was decisive in the creation of a particular artwork is visually conveyed through its pure message. For the reception of the artwork to be clearer for the wider audience, it is important to focus not only on the artist’s conscious approach but also on their artistic credo and self-identification behind the work. These direct pieces of information serve as guiding indicators for the true interpretation of the artwork.

The Parallels Between Modernism and the Visuality of Roma Painters in the Universal Space

Alongside traditional Roma visual art, the early signs of Modernism began to appear in the works of Roma artists from the 1930s to 1940s. In my view, a distinctive parallel can be drawn between Fauvism—an artistic movement of Modernism characterised by raw, wild colours—and modern expressions in Roma painting. At the time, Fauvism faced similar criticism, with some suggesting that the works resembled the “daubery of savages”. In the palette of Roma visual art, one can observe similar aspirations: returning to the basics with pure, unmixed colours, creating dynamic surfaces with vibrant, autonomous colours that convey a sense of depth, while avoiding the realms of perspectival representation. By eschewing colour mixing—sometimes delineated by contour lines and dynamic raw colour contrasts—the essence of the colour itself and its intensity form the beauty of the paintings, while maintaining a visual representation of their own perspective.

As predecessors to the Fauves, the movements of Impressionism, Neo- and Post-Impressionism, and Pointillism, along with the works of indigenous peoples, including those of Oceanic nature tribes or African tribes, are also considered influences in their work. Roma painters, emerging from their subculture with their instinctive use of colour energy and intensity, hint at a raw and bold creativity, which suggest an innate primal force—an exuberant visuality that can already be found in the early paintings of János Balázs. When an artist consciously returns to the visuality of archaic cultures and successfully discovers the “ancient pure source”, it provides the painting with an original essence that could shift market demand[9] in a positive direction.

While Fauvism is considered modern painting, its roots extend into the traditions of indigenous peoples and tribal cultures, emphasising belonging within one artistic space and the timeless connection of interrelations and harmonies. Similarly, Roma painters in Hungary, emerging in the 1930s to 1940s, began creating value-driven works with primal force, returning to dormant ancestral energies to create their visual identities.

Although the modern tendencies in Hungarian painting are traced back to Fauvism, originating from the painterly individuality of Henri Matisse, Roma visual art’s Modernist inspirations also find parallels in the identity interpretations of Marc Chagall[10] (1887–1985), the Russian-French modern painter.[11] Chagall’s dual identity, stemming from his Jewish minority background in northeastern Belarus and his experiences within social processes, mirrors the experiences of domestic Roma painters. The difficulties stemming from minority status—Chagall’s closed Orthodox Jewish religious community and its rules, and the harsh social circumstances, the state of being marginalised by society—created strong internal tensions and expressive motivations in the artist’s psyche, urging him to break through every circumstance and rule system with his bold self-expression and surprising innovative developments in his creative processes.

This kind of liberation is characteristic of Modernist Roma visual art as well, transforming inherent and acquired disadvantages into positive value communication. The surrealistic representation of a world detached from reality, dreamlike images, fragments of memories, and expressive bursts of internal tensions are typical on the canvas, marked by bold colour choices, novel technical solutions, and unique compositional arrangements. This form of colour and form-breaking is seen in the works of several Roma artists from earlier periods, as the visual traces of societal processes are evident in their creations.

In international Roma painting, the influence of Modernism can also be traced in the work of Sandra Jayat, a contemporary and friend of Chagall. The experience of minority belonging within a given society and the influence of life circumstances on artistic ambition can be clearly followed in the works of both Chagall and domestic Roma artists. In the context of inherent ancestry and environmental externalities, the powerful interpretation of inner artistic aspirations is characteristic, revealing the unique strength of talent and elevating the resulting product into an artwork. In Hungary, in the works of János Balázs and Márta Bada, aspirations similar to Chagall’s art are observable, with Modernist expressive motivations evident in their visual language.

Just as the artistic personas of Henri Matisse and Marc Chagall influenced their contemporaries, similarly, the painterly individuality of János Balázs sparked a bold, instinctual, visionary painting style free from conventions and rules. Although Roma artists traditionally created art while living segregated on the lower social strata of society, they nonetheless connect in an archaic manner to the universal flow, synchronizing with the collective unconscious and sharing similar aspirations with international art representatives. This stems from an instinctive ancient knowledge that, through a collective subconscious identity, maintains the presence of seemingly marginalised groups in its interconnectedness and unity. This shared, ancient creative source serves to organise their works into a harmonious canon, which, over time, positions them within a singular artistic space.

Alongside the more archaic manifestations of early Roma visual art in Hungary, autodidactic modern Roma visual art began to emerge, with artists expressing themselves through a liberated thematic world and varied techniques developed through self-improvement. The later emergence of professional artists—those with art degrees—equipped with universal art knowledge and skills, developed distinct artistic concepts. Tamás Péli[12] was the first to appear in Hungary with a professional art diploma, and he had a motivating influence on his contemporaries, though later on, pursuing art studies at state universities became more popular.

The illustration of the process of Roma visual art and its evolution through a differential set diagram[13] shows the different manifestations of Roma visual art, their interrelations, and the artist figures emerging in the intersections, such as János Balázs and Tamás Péli. It also highlights the artists on the edges of these sets, like politically engaged artists such as Ómara, who, through strong messages and opinions, holds up a mirror to our society.

At the same time, today we also see young professional painters who graduated from the Hungarian University of Fine Arts, such as Norbert Oláh. He reflects on the heavy burdens of the relationship between the majority society and the Roma people, formed over centuries, while maintaining a unique artistic approach. With his artistic freedom and irony that dissolves the tension between majority and minority contexts, he created Roma figures set in outer space. By expanding the “Roma question” into space, he emphasised in his speech at the opening of the exhibition, Shanco in Motion, that “he pays his full respect to the Roma activists and Roma civil rights experts, but no one does more for the Roma cause than he does”. With his new paintings, Roma are colonizing Mars and the Moon and establishing the Roma self-government of the universe.

These dynamic internal and external processes provide an organically changing surface for further investigation and documentation in today’s context, as Roma visual art is currently being reborn. Its contemporary forms, with performances and evolving events, present an exciting, organic surface rich in values that invites ongoing research into this evolving and vibrant art form.

[1] Erik H. Erikson: Dimensions of New Identity: The 1973 Jefferson Lectures in the Humanities, Norton & Company, New York, 1974.

[2] Molnár, Péter: “The Application of Piaget’s INRC System to Erikson’s Developmental Stages Across the Lifespan”, in: Hungarian Psychological Review, Márta Fülöp ed., Journal of the Hungarian Psychological Association, 2004, 537-559.

[3] Without claiming completeness, it is important to mention the scientific work of social psychologist Ferenc Pataki (1928-2015) on identity, or the social identity theory developed by American psychologists John Turner and Roger Brown in 1978. In the 1970s and 1980s, John Turner and Henri Tajfel developed the social identity theory, which examines the formation and relativity of identity interactively, focusing on the external circumstances affecting the individual.

[4] Fredrik Barth (Germany, 22 December 1928 – Norway, 24 January 2016), a Norwegian social anthropologist, developed the Model of Social Organization (1966), in which the individual is not merely a bearer of the traditions, norms, and values of a given cultural context, but also an organic shaper and reactive subject of it. His work on identity, Ethnic Groups and Boundaries (Barth 1969a), is particularly significant.

[5] He further developed the model of ethnic identity through reflections on cultural pluralism, in which he discusses the influence of history on the present day, such as the impact of social exclusion or the traumatizing effects of the Holocaust and its transmission, which can still be traced in contemporary times.

[6] Ten different types of intelligence are now distinguished, each responsible for a different area, with their existence and level each advantageous in certain situations.

[7] The formation of all of these identity elements is a lifelong process, changing with our life stages and various roles, influenced by external interactions and events.

[8] A concept used in the science of social psychology, which has a universally influential role on the entire personality, affecting all other components as the central element of identity awareness.

[9] The system of market demand and collector perspectives is not examined in this paper.

[10] Born in a poor village in Vitebsk into an Orthodox Jewish family, the painter broke the strict rules of his religion with his bold and daring artistic experiments.

[11] Halász, Levente: “Who Does Not See the Bible, but Dreams It”, in: Literary Present, Literary and Artistic Portal and Journal, 16 March 2020.

[12] Tamás Péli (Budapest, 1948 – Budapest, 1994), graduated in mural painting from the Royal Academy of Amsterdam circa 1970.

[13] One of the results of my doctoral thesis, which deals not only with illustration but also with its definition and analysis.

Dr. Barbara Bódi is a Researcher at the Hungarian Academy of Arts, Budapest

Leave a Reply