Claiming the Past by Occupying Contemporary Spaces and Minds

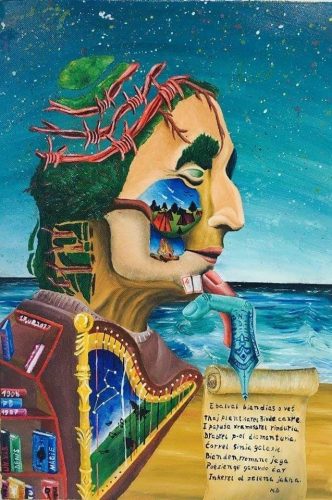

Ana Maria Gheorghe: Knife (sign of the Romany zodiac), 2019, oil and acrylic on canvas. Photo courtesy of the artist, from a private collection.

Long gone are the times

When Roma wandered around,

But I still see them.

They are like running water

Always running away

[…]

(Papusza: Water that always wanders)[1]

I think I became a feminist the moment I started to defend my mother and aunts from the violence they suffered. I have learned that I am a feminist thanks to the feminist books I have received as a gift from another minority feminist, non-Roma, Debra Schultz, and in 2002 by meeting Kimberlé Crenshaw. Being a feminist did not give me comfort, but rather discomfort, by losing those Roma men and women who used to be my friends, by losing the solidarity of some of the non-Roma feminists who did not understand where I come from, nor my emotions and inner conflicts, or the competing and conflicting ideologies I faced. I thought that both Roma and non-Roma will understand that I cannot essentialise any of my identities: Roma and woman. It took me years to come to terms with myself.

You may wonder what this testimony has to do with Romani art and mobilisation and claiming the past. First of all, because my body, my personal history, my contribution to the Romani world is an act of history and resilience which has to be archived, documented and shown to the world. I am sure that there are so many stories which may become the manifest of our resilience. Mine is a privileged position, as I have access to a scene and to spaces to expose this. Given this privilege, I have to confess I was not aware of the way it might be used for the good of my people. I hope to learn to do so in this life.

One of the paths I took in trying to come to terms with myself and trying to answer to challenges, I received from my late husband and partner in activism, Nicolae Gheorghe. He was not the only one challenging me constantly, but his challenges counted the most for me, as they were the most intellectually qualified, and they hurt the most. The path I took was to make efforts to contribute to what we started to call a new Romanipen.

Thus, I joined Ciprian Necula and Oana Toiu in the organisation they founded, Romano ButiQ. Together with many other precious colleagues, we tried to initiate a Roma Museum in Bucharest. Later on, I became involved in the Roma Archive as its Chair, and the Alliance of Roma for the European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture.

In the past decade, I became aware of the power that lies in the act of the arts, when it comes to combating the daily racism encountered by our children and our people. How can we act beyond only reacting to all this, and start thinking strategically and in the long term, for many generations to come after us? How can we better demount, deconstruct and combat all the colonial behaviour, when it comes to the Roma, only by showing to the world the immense creative power, both through history and in contemporary work?

Maybe for some of us, the acts of some Roma artists mean too much or go too far. But I say, let us look at these challenges, as they show us what we are missing in our discourse, and what we are not recognising from the reality of our people. With new waves of migration towards Western Europe, we have an entire second generation of young women and men who are either prisoners of the patriarchal culture, or are lost, not knowing who they are. Our duty is to create spaces where they may discover a multitude of ways of being Roma.

I once thought of an art project combined with journalistic research, which would document a hundred ways of being Roma today. From Turkey through the Eastern bloc to the Balkans, and to Northern and Western Europe, documenting the ways in which the Romanipen, the Romani identity, is performed every day: Christians, Muslims, Neo-Protestants, feminists, traditionalists, migrants, different generations – and we may continue with layers upon layers.

The Roma arts should occupy spaces from our own homes and the streets we live in, to public space, and both unusual places and mainstream venues. Virtual space should be occupied, too – but this is not enough. As I said in my interview for ERIAC, the Roma monologues for a Roma nation, digitalisation and technology will permit us to construct nodes of Romani identities, to be connected virtually.

We need to occupy any space we can in displaying our identity, our pride – but also to protest, both against racism and patriarchalism. Young artists have more guts than our generation: they are educated to think that we have the power to decide how one can be a good Roma, Romni. We, the elite of the Roma movement, sometimes ignore the young talents, and we pick only those who fit our view on what the Roma message and behaviour should be. In this way, we feed the gadje (non-Roma) an image which also corresponds to their expectations for us to obediently assimilate. I will never say that these acts of the arts are not valuable; to the contrary, they are extremely valuable, but no more than those that provoke everybody, including us.

The artistic act does not only mean the elevated, intellectually “clean” display of the realities we live and encounter. Many of the discussions I have had with Romani activists remained within the sphere of questioning whether or not something was art. My answer was always that for me, if art has a message for others, it does not matter what form it takes. The hip-hop song of the women’s band in Serbia, Pretty Loud; the manifesto sung by the rap artist from Spain, Arabay Flamenco; the complex manifesto displayed in the play, Roma Armée, produced by the Gorki Theatre; the strong, powerful message the play, Big Shame, by Alina Serban sends about slavery in Romania – are all very much acts of political engagement, of resistance, produced with so few resources and a lack of spaces of expression.

During the last decade of my endeavours, I have started to appreciate and respect more than ever the artistic expressions, which in fact, constitute the basis of a nation, which even without territory, government, budgets or resources, has succeeded to exist and to impact others. Until recently, I have been ignorant when it came to my people’s artistic resources, thinking that they only belonged to the early 1930s, but due to my roles in the Roma Archive and the Roma Museum in Bucharest, I have discovered amazing treasures in the arts. I thought, due to the speed in which we had to react to all the racism around us (starting with houses burned down, pogroms and police brutality) in the early 1990s after the fall of Communism, that the fight for Roma rights was the most important, and I didn’t have time to reflect and pay attention to what other peoples and nations have as their patrimony.

There are efforts to claim our past by the work of young artists, and I would like to introduce the work of the visual artist, Romanian Roma, Denis Nanciu. He is a young artist I admire very much; since he was in high school, he has been engaged in political art. This piece is called Papusza Bronisława-Wajs, and it represents in a wonderful way the creation, poetry and life of Papusza.[2] The question is how a Roma artist got to know so early about Papusza. It was his research for his identity, not found in spaces allocated or constructed by us for our people. We must ask how we can encourage others to become like him, by discovering the past to claim the present Romani identity with dignity.

Denis Nanciu: Papusza Bronisława-Wajs, 2017, oil on canvas. Photo courtesy of the artist, from the author’s private collection.

Another artist who represents a feminist voice, who I had the privilege of meeting at the ERIAC exhibition, Roma Women Weaving Europe, in 2019, is Ana Maria Gheorghe. A Romanian Roma, she now lives in Germany. Her artwork touched me as a representation of the modern young Romani woman. She herself is full of life, and her art is vivid but also very timely and unexpected.

Ana Maria Gheorghe: Knife (sign of the Romany zodiac),[3] 2019, oil and acrylic on canvas. Photo courtesy of the artist, from a private collection.

While the idea of a museum as a static construct is valid, I think it is perhaps not the best form to respond to the needs and realities of our people. Virtual spaces and itinerant mobile units may ultimately be the best fit for us, Roma. To occupy with mobile units, spaces in Roma slums, or in the central parks of big cities, these might succeed in making these spaces more attractive, and while playing with itinerant stereotypes, we may actually construct a positive impact in the minds of others.

Dr Nicoleta Bitu has been active in the field of human rights and women’s rights for over 30 years, at the forefront of the European mobilisation of Romani women activists, and of advocacy for the rights of Roma. A recognised and published expert in her field, she is the founder of Romani CRISS, served as Director of Romano ButiQ, and offered consultancy to the Open Society Foundations, the Council of Europe, the European Commission, made a major contribution to the establishment of ERIAC: European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture, and served as Chair of the Roma Archive. Her work has provoked the Romani and feminist movements to think and act based on the universality of human rights when it comes to Romani women. The foundation of her training and development is the work she has done in the early years of her activism, in local communities affected by inter-ethnic conflicts, and her encouragement and formation of new generations of Romani activists of all genders is widely recognised.

[…] Previous Blog Entry […]