Unexpected Encounters: Polish Pavilion at the International Art Exhibition — La Biennale di Venezia

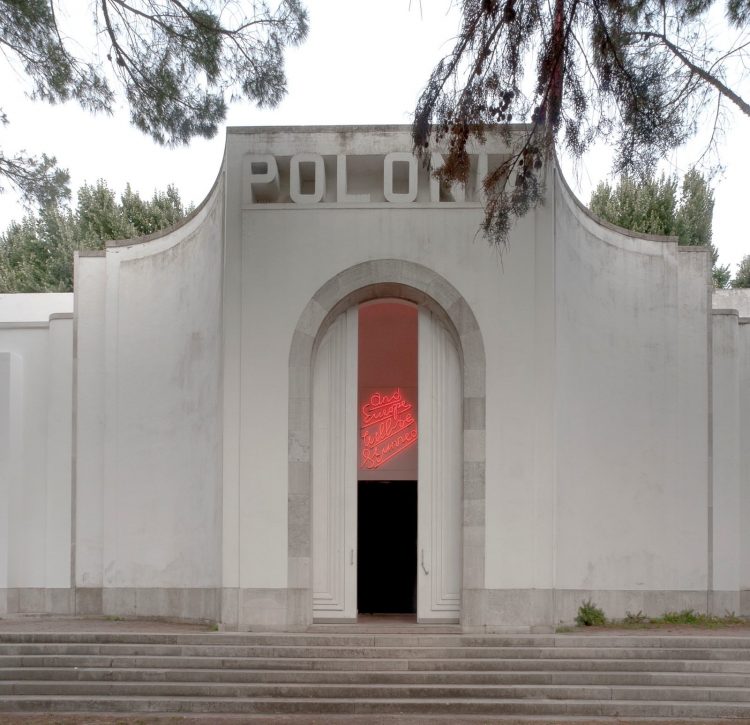

Yael Bartana: “…and Europe will be stunned”, Polish Pavilion at the Biennale Arte 2011. Photo: Ilya Rabinovich, courtesy Zachęta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw.

On 28 September 2021, a jury assembled at the Zachęta – National Gallery of Art to select the winning curatorial project for an exhibition to be held at the Polish Pavilion as part of the 59th International Art Exhibition in Venice in 2022 (La Biennale di Venezia, 23 April – 27 November 2022, curated by Cecilia Alemani, theme: The Milk of Dreams). Appointed by Professor Piotr Gliński, Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Culture, National Heritage and Sport, the members of the jury: Mateusz Adamkowski, Maciej Aleksandrowicz, Piotr Bernatowicz, Jacek Friedrich, Alicja Knast, Agnieszka Komar-Morawska, Joanna Mytkowska, Joanna Malinowska, Barbara Schabowska, Sylwia Świsłocka-Karwot, Andrzej Szczerski, Jarosław Suchan, Tomasz Wendland, Hanna Wróblewska (Head of Jury) and Karolina Ziębińska-Lewandowska, issued the following statement: “Having analysed and thoroughly discussed all submitted projects, the jury held a two-stage open vote deciding on the project for an exhibition of Małgorzata Mirga-Tas’s work Przeczarowując świat [Re-enchanting the World], presented by curators Wojciech Szymański and Joanna Warsza. The jury has taken note of the highly attractive visual form (opening the pavilion to wide audiences), combined with an original and deliberate construction ‘advancing a new narrative of an on-going transfer of images and mutual influences between Roma, Polish and European cultures’. The artist’s personal experiences and local stories become intertwined, amongst others, with the tradition of Renaissance murals in a most creative fashion, while private iconography merges with age-old symbols and allegories”.[1] It seems worthwhile to pause here and survey the history of Polish and Roma participation in the Venice Biennale.

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas: Esma Redźepova / Herstories, 2021, textile banner. Photo: Marcin Tas.

Polish Pavilion

Running for six months, shows mounted at national pavilions in the exposition space of the biennial (Giardini and Arsenale) and across the city of Venice present projects from the four corners of the world. The first biennial took place in 1895, putting mostly decorative art on display. In the early 20th century, as the public was growing increasingly attracted to it, the event gained international acclaim – and from 1907 on, foreign national pavilions were installed. At the time, Poles were citizens of Prussia, Austria-Hungary or Russia, as their country had been erased from the map of Europe in 1795. Art offered them a good opportunity to accentuate their presence. In 1860, the Towarzystwo Zachęty Sztuk Pięknych (TZSP, Association for the Encouragement of Fine Arts) was established in Warsaw, in the Russian Partition, gathering together artists and art lovers. Its main objective of supporting and popularising Polish art was pursued by means of compiling a national collection of art, providing assistance to young artists (grants), publishing, staging exhibitions and competitions. Thanks to the efforts of the Association and the generosity of the public, enough money was collected to open the Zachęta National Gallery. The construction of its seat commenced in September 1898, and the Gallery was officially opened on 15 December 1900. International exhibitions displayed artworks by Polish artists representing the occupying countries.

In 1851, the Great Exhibition in London included only two sculptures by Polish artists who represented Prussia. Polish contributions to the economic sector were more impressive, even earning some prizes. Four years later, the opportunity to retain a presence on a European forum arose again at the 1855 Exposition universelle des produits de l’agriculture, de l’industrie et des beaux-arts. The next show in London (London International Exhibition on Industry and Art), held in 1862, was important as it marked the entrance of Polish martyrology onto the international scene – a martyrology which would repeatedly replace promotion of the future and the will to undertake reconstruction. Artur Grottger’s dramatic pieces were put on show, but European audiences preferred economic exhibits. Even Polish newspapers took little interest in the appearance of Polish artists in London. In 1867, the Exposition Universelle was staged in Paris. A painting by Matejko (awarded the gold medal) acted as bait – a vast, colourful, dynamic and expressive composition did not shy away from controversy in terms of historical accuracy, but it managed to capture the attention of viewers, who demanded an explanation of its content – and they received it within reviews; indeed, it can be stated confidently that Matejko’s sensational paintings, whose artistic merit might have been considered dubious, helped to raise public awareness of the fate of the Polish nation. The 1873 World’s Fair in Vienna (Ausstellung 1873 in Wien) included ten of his pictures. At the 1878 Exposition Universelle in Paris, Matejko won the Grand Honourable Medal. The same distinction (Grand Honourable Medal) went to Henryk Siemiradzki, who had achieved recognition already in Vienna, but because the subjects he depicted failed to relate directly to Polish national matters, he tended to be associated with the Russian section of the exhibition, as it was there where his works were presented. An exceptional manifestation of Polishness came with the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, known as the World’s Columbian Exposition, as it celebrated the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s discovery of America. Chicago’s population of Poles was the second largest in the world (with Warsaw taking first place), and the Polish show attracted a wide and enthusiastic audience. The event was widely publicised by Polish newspapers, while American journalists claimed that the Polish and French fine arts sections outdid the others. The ambition to display a great number of artworks and organisational issues brought chaos and inconsistency in the choice of works, a situation that was to reoccur in the interwar period. At the 1900 Exposition Universelle et Internationale in Paris, a very Art Nouveau show, the gold medal was awarded to Józef Mehoffer. The participation of Poles in the 1910 Exposition Universelle et Internationale in Brussels was meagre and unimportant.

After the First World War, the biennial in Venice was beginning to become as we know it today – its focus shifted towards modern art and the events taking place in the interwar period, and featured works by many artists whose names are still remembered today. This coincided with Poland regaining independence in 1918 and joining the biennial as an autonomous state in 1932. A pavilion was funded by the Polish government, and the building has since remained its possession. Polish artists could now show their pieces as representatives of their own country. Bearing in mind rather extensive experience in exhibition organisation and strategies, success would seem easy and certain, but the traumatic history of a nation strongly attached to its heritage and with a tendency to dwell on the past meant that countless chances were squandered, and content failed to capture the attention of foreign viewers. On the other hand, the exhibitions that took place in 1932, 1934, 1936 and 1938 were considered insufficiently patriotic in Poland. Antoni Słonimski, a Polish writer and columnist, made a caustic comment in 1937: “The Polish Pavilion is no good at serving its propagandic role, let’s be honest – it does nothing to enrapture a visitor who comes to view the exhibition. It shows no photomontages depicting the mightiness of the Polish empire (…) Naturally, an advocate of national brawn believes this to be a scandal”.[2]

From 1930, the exhibition was no longer staged by municipal authorities: the fascist government of Italy took over. New events were added to the biennial: Venice Music Festival (since 1930), and Venice Film Festival (since 1932). After the six-year interlude caused by the Second World War, an international exposition was held again in 1948. In compliance with the pre-war tradition, special prominence was given to contemporary art. Put on view in the Polish Pavilion were works by Jan Cybis and Tytus Czyżewski. There was no Polish exhibition at the next biennial, as the Cold War and Iron Curtain were beginning to take their toll. Part of the Eastern Bloc, Poland sent her representatives to Venice only irregularly, and their expositions were controlled and censured by state authorities, rendering them rather uninspired. A wave of public protests in 1968 precipitated a general crisis of the event. Exhibitions devoted to specific subjects that accompanied the biennial rose in importance. In 1974, the show was dedicated to the Republic of Chile – an act of artistic demurral to Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship. In the late 1990s, curator Harald Szeemann introduced many Asian artists to the show. It was from that time on that the ‘national’ and ‘European’ framework of the biennial began to erode away.

The political transformation in Poland that came in 1989 stimulated a revival of the Polish Pavilion. Anda Rottenberg was appointed to the role of curator in 1993, and the exhibitions that followed were one-person shows: 1990 – Józef Szajna; 1993 – Mirosław Bałka; 1995 – Roman Opałka; 1997 – Zofia Kulik. The Venice Architecture Biennale was first staged in 1980, but it was only sixteen years later that Poland joined in (1996). Our first appearance at the Sixth International Architecture Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia was hardly a successful one. The first architecture show in the Polonia Pavilion in 1996 was curated by Olgierd Czerner, an architect and historian of architecture, and professor of the University of Technology in Wrocław. An expert in historical architecture, historical buildings and their preservation, Czerner mounted a display of photograms, photographs and reproductions of drawings depicting recently erected Polish office blocks, hotels and shopping centres. The exhibition presented the latest achievements of selected architects responsive to current needs, including banks, department stores, shopping centres, workshops, factories, business offices and posh apartments. It is often argued nowadays that postmodern architecture should undergo conservation; however, back in the late 20th century, the idea to display at the leading international exhibition, buildings in a style that had only been abandoned less than twenty years prior, was met with harsh criticism. Admittedly, their quality was evidently lower than that of postmodern architecture in the United States, Great Britain or the Netherlands. The style of exposition was also disapproved of: lack of experience in staging architectural shows and limited funds led to a display that looked provisional, chaotic and unprofessional. As the exposition was considered a fiasco, the Polish Pavilion in the Giardini was rented out to other countries, for want of ideas as to a Polish contribution to the Architectural Exhibition for the next eight years.

Poland evidently needed a fundamental rethink of its involvement in Venice shows – and finally it worked! In 1999, Katarzyna Kozyra’s Men’s Bathhouse presented at the Polish Pavilion received an honourable mention. In 2008, the highest prize – the Golden Lion of the Architectural Exhibition – went to the Polish Pavilion for the exposition entitled, Hotel Polonia: Afterlife of Buildings; in 2012, the show, Making the walls quake as if they were dilating with the secret knowledge of great power, received an honourable mention.

Krzysztof Wodiczko: Guests, Polish Pavilion at the Biennale Arte 2009. Courtesy of the artist and Zachęta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw.

The erosion of national pavilions was laid bare in the new millennium. In 2009, Krzysztof Wodiczko’s Guests portrayed migrants, ‘eternal guests’ who are never ‘at home’. The concepts of ‘Others’ and ‘Strangers’ are central to his artistic practice that encompasses projections, vehicles, as well as state-of-the-art instruments allowing those who, denied any rights, are voiceless, nameless and unperceived to have their say and gain visibility in public space. The artist teamed up with immigrants living in Poland and Italy, who had arrived from all over the world: Chechnya, Ukraine, Vietnam, Romania, Sri Lanka, Libya, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Morocco. In the Venice piece, Wodiczko integrated his earlier indoor projections presented at art galleries or museums, which had opened the closed world of art with the performative nature of outdoor projections that animated the façades of public buildings with his protagonist’s faces and hands, and enlivened them with the sound of their voices. This was when the FIRST ENCOUNTER happened. The Polish Pavilion hosted the Perpetual Romani-Gypsy Pavilion, which I will discuss later on. Wodiczko’s interests in Roma affairs gave rise to Out/Inside(rs) in 2013. Exhibitions held in particular pavilions underwent a transformation, and the nationality of artists and curators paled into insignificance. In 2011, Poland was represented by an Israeli artist. The main focus of Yael Bartana’s film trilogy is the Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland – a fictional political organisation with the objective of bringing over three million Jews back to the land of their ancestors. The action of the films takes place in a symbolic space severely affected by ethnic and armed conflicts, featuring problems of the Israeli settlement movement, Zionist dreams, anti-Semitism, the Holocaust, and the Palestinian right of return. The sections of the trilogy were: Nightmares (2007), Wall and Tower (2009), and Assassination (2011). The exhibition was accompanied by A Cookbook for Political Imagination: far from being a traditional catalogue, the collection offers a rich assortment of political instructions and formulas contributed by several dozen authors. It seems worthwhile mentioning here the Seventh Berlin Biennale (curated in 2012 by Artur Żmijewski, Joanna Warsza and the Wojna collective), as this was where the SECOND ENCOUNTER happened. In his famous manifesto, Applied Social Arts, Żmijewski – an intransigent artist, filmmaker, and editor of Krytyka Polityczna – insisted that art should exert a real effect on society and politics. The European Roma Cultural Foundation got their message across at this Seventh Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art: the Roma community emphasised the need to finish the Roma Holocaust Memorial and unveil it with the survivors. The Romani Elders met in Berlin on 1 June 2012. Such a meeting had been proposed by Tímea Junghaus, recalling the tradition of authorities standing guard over the values holding the community together, and their historical function of providing the group with representation on the outside. Importantly, the action laid stress on the right to self-representation and the need to heed the voice of Roma leaders, which, if ‘heard,’ can prove inspirational to other political and social activists. On the following day (2 June), symbolical occupation of the area around the deserted construction site was staged. Call for Unity! pressed demands for the completion of the monument and the recognition of the Roma Genocide as a relevant fact in world history and collective memory.

In 2013, Polish curators and artists were invited to contribute to other pavilions in Venice: Karolina Breguła took part in the show held at the Romanian Pavilion; Adam Budak was asked to curate the Estonian Pavilion; and Joanna Warsza, winning a competition, was made curator of the Georgian Pavilion. The Polish Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale included a monumental panoramic screening, presenting the making of Halka, an opera by the Polish composer, Stanisław Moniuszko, which took place on 7 February in Cazale, a Haitian village situated in the mountains, north of the country’s capital. The artists, C.T. Jasper and Joanna Malinowska, who represented Poland, decided to put on a performance of Halka in Haiti, inspired by the obsessive desire of Werner Herzog’s protagonist Fitzcarraldo, who set out to build an opera in the Amazon jungle. Fascinated with Fitzcarraldo’s faith in the universal power of opera, but not less aware of the undue neutralisation of his stance based on colonial relations, the artists took upon themselves the task of going ahead with this lunatic plan in a specific socio-political situation. They chose Cazale, a place inhabited by the descendants of Polish soldiers who had fought in Napoleon’s legions. Sent in 1802 and 1803 by Napoleon to suppress the rebellion of black slaves in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, these Poles – who went into the legions to fight for the independence of their own country – had turned against their French commanders and joined the rebels. In recognition of their involvement, the Constitution of independent Haiti awarded them equality with the republic’s Black citizens. The inhabitants of Cazale continue to call themselves Le Poloné and bear creolised versions of Polish surnames. Two years later, Poland was represented by Sharon Lockhart (USA), who explored the question of the doubly-excluded: young people living in a community house, suffering from social and economic exclusion, as well as minors in general, excluded from the right to self-determination. The project had a strong link to Poland. The artist had been developing it for a decade; it was inspired by her encounter with a girl called Milena in Łódź, from whom the artist had learned about the Youth Sociotherapy Centre in Rudzienko. Girls from the Centre were the partners and protagonists of Lockhart’s Venice project. At a theoretical level, the work drew on Janusz Korczak’s pedagogical ideas and practices. Korczak, whose real name was Henryk Goldszmit, was a pedagogue who believed that children should be treated as partners with a right to self-governance and supported in self-development. He was a pioneer of pedagogical diagnostics and a harbinger of children’s rights. He was a Jew/Pole and identified as both. Korczak, the staff of his orphanage (including Stefania Wilczyńska, Natalia Poz, Róża Lipiec-Jakubowska and Róża Sztokman-Azrylewicz), and some twenty children were transported to the Treblinka extermination camp during the so-called Grossaktion – liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto. Although given an opportunity to escape, Korczak chose to accompany ‘his’ children into the gas chamber. Lockhart was especially intrigued by Mały przegląd [Little Review], a periodical that published articles by children alone, edited by Korczak, who also authored King Matt the First, a symbolic story about paedarchy. From 1926 until the outbreak of WWII, Mały przegląd came out every week as a supplement to Nasz przegląd, an ‘adult’ newspaper. The theme of the 58th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia was: May You Live in Interesting Times. Poland was represented by Roman Stańczak. And now, in 2022, Poland will be represented by Polish-Roma artist, Małgorzata Mirga-Tas.

C.T. Jasper & Joanna Malinowska: Halka/Haiti 18°48’05”N 72°23’01”W, Polish Pavilion at the Biennale Arte 2015, still from a multichannel video projection. Courtesy Zachęta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw.

Roma Presence in Venice

Tímea Junghaus was the first to offer the yet unrivalled definition of contemporary Roma art. Every word in the phrase ‘contemporary Roma art’ is meaningful. This art is contemporary because it fails to match the vision of Roma art as a folkloristic relic of the past. This art is art despite the fact that its status (it tended to be classified as naïve art or craft) has been frequently questioned and, most importantly, this art is Roma art. Although national labels in contemporary art make little sense nowadays – descriptions such as Polish, French, Romanian or Latvian art are exclusively adjectival – ‘Roma art’ is a trend in art closely connected with the broader cultural context of Roma functioning in the realm of art, as well as all of culture and society, and striving towards developing an artistic vocabulary that will visualise their challenges (similarly to other types of the art of emancipation, e.g., African-American art, Feminist or LGBTQ+ art). Numerous articles and curatorial essays by Junghaus discuss this. She curated the Roma section of the Elhallgatott Holocaust [Hidden Holocaust] exhibition (2004, Műcsarnok/Kunsthalle Budapest). Her Meet Your Neighbours – Contemporary Roma Art from Europe (2006, Open Society Foundations) is a kind of directory of Roma artists active in Europe. She curated the First Roma Pavilion, Paradise Lost, at the 52nd Venice Biennale (2007). It was also the first artistic event on such a scale staged by a Roma curator. The Roma Pavilion, a transnational one, in fact, was deeply critical of the biennial’s national structure dating back to the 19th century. The works on view had been created by Roma artists from England, Romania, Finland, France, Germany and Hungary: Daniel Baker, Tibor Balogh, Mihaela Cimpeanu, Gabi Jiménez, András Kállai, Damian Le Bas, Delaine Le Bas, Kiba Lumberg, Omara, Marian Petre, Nihad Nino Pušija, Jenő André Raatzsch, Dušan Ristić, István Szentandrássy, Norbert Szirmai, and János Révész. The curator intended Paradise Lost to portray the Roma community as a model group displaying European virtues (preferred at the time, e.g., mobility). In a 2013 interview, she told me that she wanted the show to be strongly optimistic, depicting Roma people in an unexpected way, as multilingual and transnational Europeans ready to keep pace with the rest, to create a distinctly positive picture of a transnational community competing with other Europeans on equal terms. It was not by coincidence that the exhibition catalogue featured an essay by Thomas Acton discussing the Second Site show that had taken place in 2006. Acton disapproved of attaching ethnic labels to art, claiming that these artists did not share a ‘common Romani spirit’, an idea evoking the discredited racist approaches to history and identity. Still, Acton had no choice but to admit that when they came together to prepare Second Site, it was obvious that the synergy between them originated from shared experience. Likewise, the positive tenor intended by Junghaus was countered by the pariah syndrome observable in the work of the artists from England, Romania, Finland, France, Germany and Hungary. A substantial number of works investigated questions related to the life and death of pariahs in Europe: anti-Gypsyism and the Roma Holocaust. The most poignant among them was Tibor Balogh’s Rain of Tears, an installation consisting of test tubes that had been filled with human tears. It contained a reference to Leaky (produced by Balogh in collaboration with Janos Bari), displayed at the Hidden Holocaust exhibition (2004). The idea to invite artists educated in art, as well as older creators who were not able to receive such education because of the socio-political situation after the war, was very interesting to me. The curator meant to accentuate the total worthlessness of divisions imposed by external categories regarding art: what is accepted as art, and what does not fit its definition; what is examined by ethnographers, and what by art historians, etc. An emblematic example of an artist of great importance for contemporary Roma art, but without a diploma in art, is Mara Oláh – Omara (1945-2020), whose creative output was included in the Venice exhibition. Her works tended to be considered naïve, primitive and amateur, but they have been increasingly present at important international expositions of visual arts. Junghaus maintains that their elusive nature poses a danger to established preconceptions and exposes a general reluctance to accept Roma art, but the artist’s career also demonstrates that this disinclination can be overcome, and the Roma identity reconstructed. Despite the fact that all the problems mentioned above (decolonisation, the question of creating one’s own representation, rejecting the ethnographic discourse) carried significant weight, crucial for the ‘pavilion effect’ was the legitimisation of contemporary Roma art: the moment it came to the historical centre of the European art world. It was the first transnational pavilion in Venice.

Regardless of the overwhelming success of Paradise Lost in 2007, the pavilion of an ethnos without its place on the map soon lost its financing. It should be noted here that the official part of the Venice Biennale takes place in the Gardini, where thirty permanent national pavilions are situated, allocated to particular countries mostly in the 1930s and during the Cold War. Obviously, the Roma never had a pavilion ‘of their own’, and the 2007 Roma Pavilion was merely an accompanying event (organised and supported by the Open Society Foundations), and it was not included in the biennale’s programme (some accompanying events are cyclic). In 2009, the official art world failed to demonstrate solidarity with Roma artists excluded from the biennial (the competition for the next ‘Roma Pavilion’ was cancelled). It also failed to react to a genuine social problem and activities of right-wing extremists. Between the 52nd Venice Biennale in 2007 and the 53rd in 2009, Italy became an arena of anti-Roma protests aimed at the liquidation of illegal settlements inhabited by Roma immigrants from Romania and Bulgaria (nota bene, contemporary concentration camps for Roma people have continued to exist in Italy since the 1960s). An encampment outside Milan burnt down already in August 2007, costing the lives of two children. A heretofore unknown Group for Ethnic Cleansing claimed responsibility for the attack and announced more arson attacks should the Roma “not return to where they’ve come from”. Hostility was fuelled by the media and the activities of the Northern League, which were soon condemned by the Commission on Human Rights and Commissioner Thomas Hammarberg. As a result, the Roma were expelled from Italy, regardless of the fact that they were citizens of the European Union and posed no danger to public security and order. Responding to these events, Damian Le Bas, together with his wife Delaine and other Roma artists, established the Perpetual Romani-Gypsy Pavilion (2009), in cooperation with Perpetuum Mobile, founded by Marita Muukkonen and Ivor Stodolsky in 2007, with the objective to “re-imagine certain basic historical, theoretical as well as practical paradigms in fields which often exist in disparate institutional frames and territories”. Meant to secure the presence of Roma artists at the biennial following their exclusion from it, the enterprise was a reaction to the refusal to officially stage another Roma Pavilion, as well as to the absence of Roma artists in pavilions of other nations. People visiting the pavilions that joined the action were asked to fill in a short questionnaire and leave their fingerprints, which is the usual practice with the Roma, as they are entered into criminalising ethnic registers. Like a virus, it ran through the different pavilions: Greek, Hungarian, Italian, Polish, Estonian, Serbian, Turkish and Uruguayan, creating horizontal structures cutting through national divisions. The initiators explained that the cards they distributed contained information about the difficult situation of Roma-Gypsies, and the reasons for establishing their pavilion, along with a set of questions for viewers to answer. There was also a life-size outline of the hand with five little circles representing fingerprints. There was a stand at each of the national pavilions, and everyone could learn how to express support by leaving their fingerprints. The support was for the Roma in Rome, around Naples, and all over the country: adults and children whose fingerprints are still taken even today (according to the European Parliament), against the European Convention on Human Rights, and against their will. The public responded positively at the preview of the biennial. On the first day, when the pavilions were opened to the general public, the action received favourable reactions. All the cards, bearing fingerprints, were soon returned. The act of pressing fingertips on the card stimulated all sorts of comments: “I haven’t done this since …: I went to the USA” or “I joined the army”. But then people also tended to wipe their hands, to try and remove the traces, the stigma: the bureaucratic instrumentalisation of racial prejudice, which must bring fascism to mind all across Europe. The Perpetual Romani-Gypsy Pavilion was held in many locations, with Malmö being the last thus far (The Invisible Faces of Europe, Moderna Museet, Malmö, 2015). In Poland, it could be seen as part of Roma Issue: A Project with Majority, Galeria “Wieża Ciśnień”, Konin, 12–20 October 2012, curated by Joanna Warsza. And this was when the THIRD ENCOUNTER happened.

In 2007-11, a passing trend for showing Roma art emerged in the mainstream, reaching its culmination in 2011: New Media in Our Hands — Roma New Media Artists in Central Europe, opened in the Műcsarnok/Kunsthalle Budapest (curated by Sarolta Péli); Berlin opened its first commercial Roma gallery – Galerie Kai Dikhas, and hosted the Reconsidering Roma — Aspects of Roma and Sinti Life in Contemporary Art exhibition (curated by Lith Bahlmann and Matthias Reichelt); Safe European Home?, a project by Delaine and Damian Le Bas, was installed as part of the Wiener Festwochen, in front the Austrian Parliament Building, while the Roma Protocol exhibition was displayed inside (curated by Suzana Milevska); the World Roma Khamoro festival in Prague included an international show, accompanied by a conference, Ministry of Education Warning: Segregation Harms You and Others; Maria Hlavajova organised a programme devoted to contemporary Roma art at BAK (basis voor actuele kunst platform) in Utrecht; and, last but not least, the same curator staged the Call the Witness show at the 54th International Art Exhibition in Venice, in the second ‘official’ Roma Pavilion. And this is where the FOURTH ENCOUNTER happened: Romski Pstryk [Roma Snap] – an exposition of illustrations to fairy tales and poems by writers of Roma descent was also presented at the pavilion. When the Polish-Roma conflict in Andrychów hit the headlines, two artists, along with a group of activists of Roma descent, set out to visit Roma districts across Lesser Poland, and took photographs that would not offer the stereotypical depiction of poverty and exclusion. Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, a sculptor, and Martushka Fromeast, a photographer, have been running the Romski Pstryk project for eight years, wishing to bring about a transformation in the way Roma people and Roma culture are perceived. The artists prepare, in collaboration with Roma communities, illustrations for fairy tales and poems.

Nevertheless, according to Junghaus, the increasing number of artistic events featuring Roma art that are staged across Europe does not indicate progress. On the contrary, things have dramatically deteriorated since 2008 in Central and Eastern Europe; with their material heritage under threat, invisible and inaccessible, the Roma are denied the right to their cultural legacy, to create, display and interpret their own culture. The situation has not been so critical since the 1970s. After the third pavilion in Venice, in 2011 (the second – according to the rules of the majority world; the third, according to Roma artists who counted the ‘viral’ one organised in 2009 by Damian and Delaine Le Bas), the majority art world started losing interest in the art produced by creators of Roma origin. In 2013, Damian Le Bas, Delaine Le Bas and Gabi Jiménez, once again in collaboration with Ivor Stodolsky of Perpetuum Mobile, staged the 4th Roma Pavilion, Safe European Home?, in Berlin. It took the form of an installation located in the vicinity of the Collegium Hungaricum. The fourth pavilion and the Venice Biennale were opened concurrently, the latter without an exhibition of Roma art. The installation took for its subject matter the tension between voluntary and forced migration, between minorities and majority societies. At the 2007 and 2011 biennials, the institutional art world perceived the Roma as falling into the category of irreducible cultural difference, and Roma art seemed to them to manifest this difference and remoteness. During a discussion accompanying the Roma Protocol exhibition (2011), Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak insisted that postcolonial critique should be applied in Roma art, not only as a distant analogy, but also as a real and vital tool of securing a position for the Roma among Western democracies.

And this is where the roads of Roma biennials parted.

In early April 2018, the First Roma Biennial, Come Out Now!, took place in Berlin. It was initiated and curated by Damian Le Bas and Delaine Le Bas, and co-curated by Hamze Bytyçi.[3] The event offered an impressive programme of performative arts: classical performance acts and Delanie Le Bas’s installation, Romani Embassy, a production of Roma Armée, and an impassioned gig by Äl Jawala. The programme also featured less obvious performative forms, including Hilton 437, and an interactive talk show hosted by Hamze Bytyçi with Delaine Le Bas as a special guest, as well as performances by Jilet Ayşe or Tucké Royale relating to the Der Zentralrat der Asozialen project. Possibly the most surprising was the performers’ night, Long Night of Coming Out. The performance was partly coherent with threads recurring in cycles, and partly a mosaic of forms: from actors ‘showing off’ as they once did in garden theatres of the interwar period, via stand-up, to rap; from mini performances of pantomime and ballet and ballads, via burlesque, to school assembly; from a mad multimedia show to Delaine Le Bas’s most dramatic and intimate monodrama. A biennale taking place in a theatre is naturally expected to include performative acts; however, the curators placed special stress on their connection with Roma practices involving centuries-old struggles with majority societies and performative politics, pointing out that the concept of a Roma biennial is not fixed and may depend on its location. It is all about developing strategies of flowing with life. A Roma biennial was a goal pursued by Damian Le Bas, who questioned the institutionalised system of art that took note exclusively of the events it approved of. The earlier gesture of changing the numeration of Roma pavilions, initiated, amongst others, by Damian and Delaine Le Bas, unmasked the hierarchies in the art world. Damian Le Bas’s critical attitude towards the unambiguous project of a single Roma identity conceived by the political movement was not less significant. In his curatorial essay, opening Come Out Now! 1st Roma Biennale, the artist compared his dream of a Gypsy Europe to the world Martin Luther King Jr. spoke about. Taking the form of imaginative maps, the pieces of Le Bas, who admitted to be fairly poor at reading and writing, expressed his resistance against racism and right-wing propaganda. He called for unity and recalled the fact that the Roma remain an object of pursuit. Le Bas died on 9 December 2017, at age 54, before the biennial occurred. Long Night Of Coming Out, a long and moving speech by Delaine Le Bas, his artistic partner and widow, stressed that he never gave up his dreams and thus set the goals for the others. Questions addressed in Berlin were as progressive as it gets: Romafuturism in reference to Afrofuturism. Afrofuturism emerged in response to a sense of history’s incompleteness; still, rejecting ‘defence-driven identity’ provides space for alternative scenarios, some of them positive, and totally new approaches to historical processes. In this regard, Afrofuturism establishes alternative models of identity narratives heretofore absent from (popular) culture, covering such categories as race or difference – these are, however, first reinterpreted and revalued (liberated from their stigmatising power, the burden of westernisation or condescending Eurocentrism), inventing ‘fantasy vehicles’ – in the form of literary, film or musical texts – helping the members of society who have so far remained on the fringes of mainstream cultural production find their own place in the imaginarium of popular culture. Within the framework of Afrofuturism, history becomes reinterpreted to include events and processes that could not take place, due to, for instance, colonial politics. The strict pan-Roma identity construct formed by the Roma political movement was violated by the artists as they applied the instruments used by Afrofuturism and openly adopted the strategy of queering Romani-ness. As Spivak writes: “Essentialism is like dynamite, or a powerful drug: judiciously applied, it can be effective in dismantling unwanted structures or alleviating suffering; uncritically employed, however, it is destructive and addictive”.[4] On a similar note, Joanna Bednarek points out: “(…) a consequence of queer theory may be the emergence of a political order in which there will be no attributes that have the power to exclude from participation, and public sphere will be determined by interactions of the bodies inside it; an order facilitating a politics within which bodies can enter relationships with one another that cannot be predefined”.[5]

At the same time, the idea of an exhibition to be staged at the 58th International Art Exhibition — La Biennale di Venezia (11 May – 24 November 2019) was taking shape, commissioned by ERIAC, and curated by Daniel Baker: FUTUROMA. Daniel Baker had been one of the exhibiting artists and a consultant for the first and second Roma shows – Paradise Lost and Call the Witness, held at the 52nd and 54th Venice Biennales, respectively. In 2018, he was selected to curate the Roma Collateral Event by an international jury consisting of Professor Dr Ethel Brooks, Tony Gatlif, Miguel Ángel Vargas, and ERIAC management. FUTUROMA draws upon aspects of Afrofuturism to explore the role contemporary Roma art plays in defining, reflecting and influencing Roma culture. FUTUROMA offered new and spontaneous re-interpretations of Roma pasts, presents and futures, via a fusion of the traditional and the futuristic, in order to critique the current situation of Roma people, and to re-examine historical events. Imagining Roma bodies in speculative futures offers a counter-narrative to the reductive ways that Roma culture has been understood and constructed — thereby moving our cultural expression beyond the restrictive motifs of oppression, towards a radical and progressive vision of Roma to come. The confluence of traditional knowledge and contemporary art practice evident within FUTUROMA combined to highlight possibilities for different ways of being. Here, artworks are rooted in the techniques and traditions of the Roma diaspora, but at the same time decisively forward-looking. The acts of remembering and imagining manifest within these artworks point towards ambitious visions of life-affirming futures and, at the same time, allow a reinterpretation of our collective pasts. In their unique manner, each of the artworks on display in FUTUROMA variously employed and deconstructed different aspects of the primeval, the everyday and the futuristic. These objects move between the familiar and the unexpected, taking us beyond the confines of time and place to a different kind of objectivity — to a place to see anew. New site-specific works emphasise the implications of materiality — physical stuff that takes up space in the world. After all, it is the Roma’s physical presence that is continually contested, marked by questions of where and how they are permitted to exist. As well as being a means to re-discover Roma history in an impactful and engaging way, the project was a chance to envision a future where Roma truly belong. Daniel Baker, the curator, stated that, “As Roma, we are too often told that we have no future — that we remain relics of the past. FUTUROMA draws together visions of our future to present an alternative perspective informed by all that came before and the promise of all that can be, placing us firmly in the here and now. FUTUROMA features fourteen Romani artists from eight countries: Celia Baker, Ján Berky, Marcus-Gunnar-Pettersson, Ödön Gyügyi, Billy Kerry, Klára Lakatos, Delaine Le Bas, Valérie Leray, Emília Rigová, Markéta Šestáková, Selma Selman, Dan Turner, Alfred Ullrich and László Varga”.

FUTUROMA opening ceremony. Perfomance by Delaine Le Bas. Photo: ERIAC.

Following the three previous shows in 2007 (Paradise Lost), 2011 (Call the Witness), and 2019 (FUTUROMA), ERIAC intends to commission and support the organisation of an exhibition in 2022. Now is the time for the Roma community to start an open discussion regarding its participation in the Venice exhibitions. During the first ERIAC LabDay organised as part of WEAVE – Widen European Access to cultural communities Via Europeana, a proposition was put forward that a permanent exposition of Roma art and heritage should be promoted. Displays by the largest European minority are considered a ‘collective event’, rather than a national pavilion. The Roma have not been assigned a national pavilion / building / space, while being the most sizeable minority for many national representations in Venice. This uncertain presence of the Roma minority at the biennial means that the Roma need to rent exhibition space in Venice in order to take part. As a consequence, the chance for a tangible and perpetual Roma representation at the most prestigious European art show is less than minimal. Meanwhile, having analysed curatorial ideas and exhibition proposals, the international jury has selected Eugen Raportoru’s The Abduction from the Seraglio, to be curated by Ilina Schileru.

The Key Encounter

Self-organised Roma pavilions have given rise to the Roma Biennale in Berlin, while the Roma pavilions that remain part of the Venice Biennale, under the supervision of ERIAC, continue their search for a way of functioning within the institutional framework of the event. There will be two Roma artists presenting their creative output at the 59th International Art Exhibition — La Biennale di Venezia, to take place between 23 April – 27 November 2022: Eugen Raportoru in the Roma Pavilion, and Małgorzata Mirga-Tas in the Polish Pavilion. Two approaches to the situation of Roma artists will be shown: the first referring to the Roma as a nation, and the other as citizens. Eugen Raportoru will be exhibiting as a national Roma artist, while the other exposition will highlight the Polish-Roma identity of the artist, and mutual influences between Roma, Polish and European cultures. I can imagine other Roma artists putting their work on display in other majority pavilions at the Venice Biennale in the future. Such an exhibition hardly comes as a surprise in the Polish Pavilion. The distant historical analogy seems intriguing, though – works addressing Polish identity issues were also presented at world’s fairs – as a part of expositions staged by oppressing forces, Russia, Prussia and Austria-Hungary.

The choice of a Polish-Roma artist is not shocking, either. The Polish Pavilion has hosted shows dedicated to complicated and tense relationships between Poles and Jews, Black Poles from Haiti – descendants of Polish soldiers sent to fight in colonies, and the Perpetual Romani-Gypsy Pavilion. The curators of the Polish Pavilion – Wojciech Szymański and Joanna Warsza – have collaborated with Roma artists and activists previously.

I hope that this coincidence will get noticed at the biennial. This is a most interesting state of affairs, which will hopefully prompt the international art world to reflect upon the art of people of Roma origin and their peculiar situation in the art world.

Monika Weychert

[1] See: https://www.konstfack.se/en/News/News-and-press-releases/2021/Joanna-Warsza-co-curating/

[2] Dexlerowa, Anna M., and Andrzej K. Olszewski: Polska i Polacy na powszechnych wystawach światowych 1851-2000 [Poland and Poles at World Exhibitions 1851-2000], Institute of Art – Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, 2005, p. 206.

[3] See: https://www.romarchive.eu/en/collection/p/hamze-bytyci/

[4] Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak: A Critique of Postcolonial Reason: Toward a History of the Vanishing Present, Harvard University Press, 1999. [The author of this text used the Polish translation: “Krytyka postkolonialnego rozumu. W stronę historii zanikającej współczesności,”, in: Teorie literatury XX wieku. Antologia, eds. Burzyńska, A., and M.P. Markowski, Znak, Cracow, 2006, p. 651.]

[5] Bednarek, J.: “Queer jako krytyka społeczna”, Biblioteka Online Think Tanku Feministycznego, 2014, p.24, see: http://www.ekologiasztuka.pl/pdf/f0132_bednarek_queer_krytyka_spoleczna.pdf;

quotation within the quotation: T. Ramlow, “Queering, Cripping”, in: The Ashgate Research Companion to Queer Theory, ed. N. Giffney, M. O’Rourke, Farnham-Burlington, Ashgate, 2009.

[…] Next Blog Entry […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here: eriac.org/unexpected-encounters-polish-pavilion-at-the-international-art-exhibition-la-biennale-di-venezia/ […]

This blog has lots of extremely useful stuff on it! Cheers for informing me.