Thoughts after Florence

Last October, I participated in a joint artist residency with a stipend offered by ERIAC and Villa Romana. The scholarship grants the opportunity for young European Roma artists to travel, build networks and broaden their knowledge by educating themselves in Florence, one of Europe’s most ancient and illustrious art centres.

Villa Romana is situated on a beautiful Florence hilltop, a few minutes’ walk from Porta Romana. Its rooftop offers magnificent views of the city together with a picturesque Mediterranean landscape. While sipping your morning coffee, you can enjoy the view of the cupola of the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore. Traversing and residing in the building is a festive experience. The classical architecture is complemented with elegantly decorated rooms that are absent any trace of ostentatious luxury.

The enormous garden hosts a potager, olive and pomegranate trees, while inside the building, visitors and staff are served by a library, atelier, residential rooms, offices and exhibition spaces. Locals and the employees of Villa Romana provide a friendly and welcoming atmosphere. The city is phenomenal. With every step, I encounter something essential we studied at university, where, during exams, if one failed to learn it thoroughly, our professor did not hesitate to fail us. The place is dense with history, but contemporary superstar artists also have their share of exhibitions here. While I was in Florence, both Jeff Koons and Jenny Saville just had their exhibition openings. I can only speak in superlatives about this place. I cannot comprehend how natural all this is for the Florentines. To me, it was not a given at all.

This was not my first time to visit Tuscany. In 2019, as a scholarship recipient of Kahan Art Space, I had the chance to spend two months in San Sano, in the villa of the main donor of the foundation. At emotional moments, I tend to feel that Tuscany, Italy, and the Mediterranean are calling me. I felt something similar in Florence, as well. It feels almost as if everything there was too beautiful. What a contrast, compared to the 8th District of Budapest, Josephstadt, where I live – and which I love, and which I have painted countless times. It is beautiful in a very different way. The ruins are different. In Budapest, the ruins are ravaged and decomposing; in Florence, they are romantic. Even the sun shines differently upon them.

It is very easy to get accustomed to middle-class life. I got used to it easily. Painting is part of my life, as I live in my studio, my paintings are sold, and thanks to my sponsors and patrons, I am able to use the best paints for my work. Not to mention the exhibitions, theatre, jazz concerts, festivals, the debauched party nights in the city, and travel. The beautiful places I used to see on postcards or in movies, or knew about from the stories of others suddenly became known to me close-up. They have all become natural to me, to the point that I can even sometimes become bored with them. But from time to time, especially when I’m in a new place, or sometimes even when I walk the streets of Budapest, a feeling comes over me. It lasts only for a moment. The fact that I’m here, that I get to do this, that I can paint in a villa in Florence after having visited the Uffizi in the morning, for the hundredth time already – the fact that I even know what the Uffizi is – is not to be taken for granted. For many who come from the social level and environment that I come from, even dreaming about all this is already quite something. In these moments, I see myself from outside, out of the context of time and space. It only lasts for a moment, but these are very good moments. These moments are my reminders. Then I stop and I say to myself: “I am here in Florence! This is fantastic!” As if I wanted to give a message to the Norbi of 20 years ago, to eleven-year-old Norbi: “Your dream came true: you have become a painter!” And then everything goes on, naturally, as before.

I’m sorry! I can only describe this feeling in sentimental terms. In any case, please, allow me to be sentimental: where else could I become sentimental, if not in Tuscany?

There is a reason for me to share this very personal feeling. In Europe, and especially in Hungary, being a Roma is not only a matter of identity; it is often also a matter of social class. An exceptionally small number of Roma belong to the middle class. The majority, like myself, come from the lower classes; poverty has an ethnic aspect, too. The media also contributes to portraying the Roma as criminals, as people living in poverty and squalor, with restricting and limiting effects on their lives. The Roma who are presented to the wider public in a positive light appear most often on star-making talent and reality television shows, but are mostly portrayed in stereotypical ways, stigmatising their environment in the process. Their personal suffering is taken out of context and overdramatized, their social reality reduced in the service of commercialisation, with human lives exploited for dirty business purposes. They are spreading lies, falsely claiming that the show is the only opportunity to break out from their desperate life circumstances, while the throbbing lights, the shiny make-up room, the elegant costumes, and the well-choreographed applause steer attention away from the fact that compared to the enormous revenue of the show, the sum attached to the main prize is ridiculously small. It rarely happens that a young Roma person dares to think of themselves as I do when I stroll the streets of Florence. In actual fact, I don’t even think about it, as I take for granted that I can be there, and others also find it natural for me to be there, and the sentimental moment is always only my own.

ERIAC is an institution dedicated to Roma culture, with the goal of supporting the careers of Roma artists and contributing to their representation. And this task is not an easy one. Its leaders and staff are aware of the significance of the experiences I have just written about. Among those of my generation, there are still many who are first generation intellectuals. We are many of the “firsts” – who have received a diploma, who think of themselves in the most natural way as citizens, as intellectuals, artists, but the question is, how many are there who are completely unaware that they could think of themselves as such, when the gates of social mobility are shut before them, and when institutions of power offer them nothing other than a reflection of distorted images.

My Roma identity is extremely important to me. I experience it in different ways, and I am also aware that other Roma people might experience it differently. It has become a part of my practice of self-reflection to observe from time to time how I relate to my identity. In most situations, my Roma identity is something natural to me when I am among my (not only Roma) friends and my family and other Roma people. It becomes painful when I encounter exclusion and ostracism. I feel uncomfortable when somebody forces this topic on me, even when I don’t find it important. In most cases, it doesn’t even cross my mind. When I go shopping, eat, brush my teeth, clean my paintbrushes, or just gaze out the window of the train and think about how interesting it is that fish move their fins horizontally, while cetaceans move theirs vertically – I don’t do these things as a Roma, just a person. But when I should be making politics or take on the role of the activist, or represent Roma culture, then I become terribly ill at ease. Because as an intellectual, and especially as an artist, it is inescapable to take on responsibility; we cannot avoid it. But at the same time, I feel a visceral resistance that comes from deep inside me, when someone wants to place me in a Roma box, or when others assign a role to me. And most of all, I despise being seen as a victim. Despite the fact that I could easily start complaining about how many people have hurt me unfairly, and there are many more who were hurt more than I was, and who underwent injustices that cannot be compensated, there are those who went through unbearable suffering – but I am not a victim. This is how I feel, and I do not ask for compensation, nor any charity. But those who feel differently are also right, and those who want to make politics, or art or culture by slamming the table and raising their voices, by speaking in the name of the Roma community, demanding their fair share, are also right.

Many of us might all feel and relate differently, and this is exactly why a leading European Roma institution needs to organise itself wisely. In the given case, it needs to provide a scholarship knowing that it helps counter social inequalities, while the grantees need to feel that their scholarship is an organic contribution to their artistic careers.

If an artist wants to carry out political representation in their artwork, and their values do not go against the values that the institution stands for, that institution needs to show support for them, but also needs to recognise that for some artists, assuming a political or activist role is alien or frightening, and the institution has to be understanding about the possible insecurities artists might have about their roles. Most importantly, support should be offered to young talented Roma, and not expectations. We are all different, and we all think differently about the world we live in. During these artist residencies, when we get to know each other, we might end up having an influence on one another, and, if we are successful, just by the mere fact of having become visible through our artwork, we provide positive representation. This is how we contribute to the goals of ERIAC and similar institutions. Nothing more or less can be expected of an artist than to work passionately on their own artwork.

It is with great respect that I thank ERIAC and Villa Romana for the opportunity to participate in their artist residency programme, and I wish much luck and success for all future residency grantees.

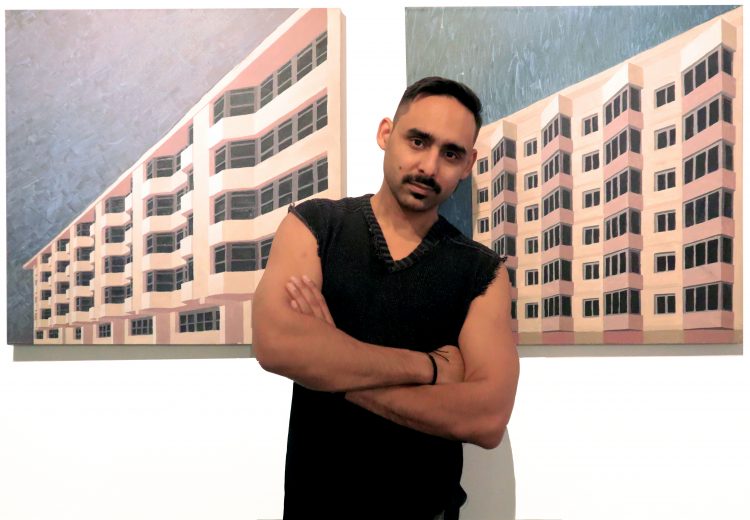

Norbert Oláh

Translated from the Hungarian by Etelka Tamás-Balha

[…] Next Blog Entry […]

[…] Previous Blog Entry […]