In which the Polish government invites a Romni to the Venice Biennale and the puzzle begins

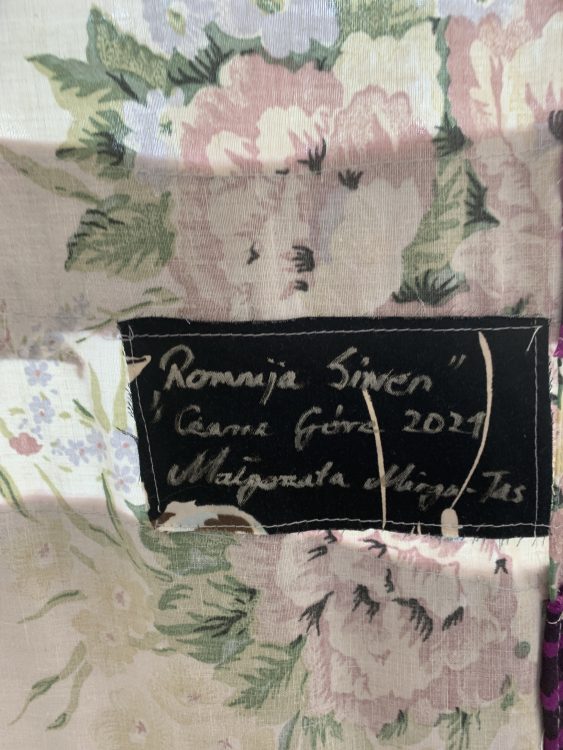

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas: Romnija Siwen / Sewing Women, 2021 (detail). Photo: ERIAC

Art most definitely speaks for itself, but La Biennale di Venezia is not just about art: it is also political, and the political language it speaks is not exactly democratic (in the sense we think of in the 21st century) or grassroots. At La Biennale, nations converse and compete, displaying their developments and achievements, hopes and concerns. This was the great message of the World Exhibitions, the spirit of which La Biennale directly recalls: the Olympic Games for the minds and imagination, where being in the Game means so much more than a victory. In the same way, presence is the core of re-presentation, isn’t it?

As we approach, however, the inclusive and benevolent construction of international spaces appears more closed and choreographed than we might have thought from afar. There is a core of benign nationalism, visible even in the name of the United Nations.[1] As if it is exclusively the quality of being a nation that gives one the right to unite. And hence, the right to be present, to be re-presented among nations.

Ethnos or nation?

The question of whether the Romani people constitute an ethnos or a nation seems puzzling. Philologically, the two words have much the same meaning, although for the Greek and Latin lovers, the Greek meaning of ethnos (ἔθνος) feels more ‘organic’, and natio, deriving from the ancient Romans, speaks more of politics and intrigue. Both stem from roots indicating being born and giving birth, and indicate something larger than just a family; in this, both legitimately correspond to the Romani. Academia and dictionaries are not of much help, either. Failing that, the references we are left with are international documents spelling political consequences for one or the other.

International documents concerning the minority rights of the Roma generally avoid tipping the balance one way or another. The Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (FCNM)[2], the first international document and a go-to legal basis for minority rights, has been purposely vague in terms of definition. In the spirit of the Convention, ensuing reports, such as the Council of Europe’s “Legal Situation of the Roma in Europe” report from 2002, have followed this vagueness in maintaining, for example, that: “The Roma must be treated as an ethnic or national minority group in every member state, and their minority rights must be guaranteed”.[3] In the wake of the EU expansion, the European Union has been tackling the issue slightly differently, as an internal question; however, for all intents and purposes, the international community remains bound by the FCNM.

On the other hand, since the 1971 First World Roma Congress held in London, the phrase “Roma Nation” has become the phrase of choice to denominate “a new, active generation of a nation without borders […] reaching for ownership of a people’s sovereignty”.[4] This self-made claim to nationhood held by arguably the largest European minority scattered among the various states unfortunately clashes with Europe’s perception of nationality. In the European Convention on Nationality, the sober restraint with respect to definitions has been sadly abandoned, as it stipulates that “‘nationality’ means the legal bond between a person and a State and does not indicate the person’s ethnic origin”.[5]

As the Convention was opened in 1997, immediately following the war in Bosnia, as well as an unprecedented re-arrangement of nations after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the need for order and clarity was understandable. The Roma people’s first claim to statehood came in 1951, however, and while it failed, it must be said that the 1997 formulation left the Roma somewhat stranded. Especially in light of the construction of the international community, which, with as much good-will as it might have, remains so focused on nationhood as to deserve a paradoxical qualification of nationalist: we will only address you if you are a nation, and you can only be a nation if you have a state, and a sovereign state at that.

So, maybe a nation?

At this point in history, the Roma people do not claim statehood – perhaps because we are all aware of the potential collateral consequences of an arbitrary attribution of a territory, or perhaps because awarding a fixed territory to an itinerant nation seems rather absurd. Nevertheless, the claim to nationhood seems increasingly justified: for instance, the efforts to collect and preserve Romani art and cultural heritage bear fruits far exceeding expectations, and in this, it fulfils the aim and the spirit of the International Exhibition, where nations can present their respective achievements to establish and introduce their identity in a spirit of solidarity.

Or, as the Oxford Research Encyclopaedia puts it, “ethnicity refers to shared cultural practices, perspectives, and distinctions that set apart one group of people from another. Ethnic differences are not inherited; they are learned. When racial or ethnic groups merge in a political movement as a form of establishing a distinct political unit, then such groups can be termed nations (…) Thus, ethnicity and nationalism form different stages along a continuum”.[6] There is a lot at stake, however, depending on where, on this continuum, one would set a demarcation point, as ‘ethnos’ spells absence, and ‘nation’ means presence and, henceforth, representation. It can be said that, for the efforts in preserving its art, traditions, and languages on the one hand, including the RomaMoMA project, as well as for the perpetuation of the World Roma Congress, now spanning half a century, the Roma people should be treated at least nation-like – at the very least, be invited to the cultural events of the nations.

Nation or not, here we come

Nation or not, the Roma will have their representation at the main event of the Venice Biennale in 2022. In a truly “black swan” turn of events, the jury of the competition for the curatorial project of the exhibition in the Polish Pavilion at the 59th International Art Exhibition in Venice have selected the project by Małgorzata Mirga-Tas: “Re-enchanting the World”, proposed by curators Wojciech Szymański and Joanna Warsza. The Jury appreciated an “original and deliberate ideological concept”, as well as “a new narrative about the constant migration of images and mutual influences between Roma, Polish and European cultures”.[7]

And therein lies the rub: why would the jury select a Romni to represent its country? The decision fell just a couple of months before a nationalist march on Poland’s National Day: what irony, for exactly a Romni to represent Poland in the Venetian context of the “concert of nations”!

Mirga-Tas, a complex entanglement

One possible explanation is that the Polish government has decided to delegate the task of the United Nations construction of the international community of a “concert of nations” to a minority artist. Another reason could be more prosaic: as Małgorzata Mirga-Tas has only recently come to prominence, she is not exactly tainted by the connection to the Polish art world. The latter, formerly a grand part of the political and cultural establishment of democratic Poland, now sits at the core of the new “liberal opposition” in an almost ritualistic game that Polish philosopher Ewa Majewska qualifies as “using one elitism (liberal) against another (conservative)”.[8] The game (if one may call it that) dates back to 2016 and, on the part of the government, involves dismissing managerial staff from most public art institutions, cancelling events, and displaying some horrendous examples of national-Catholic art in the most prestigious sites – while, in a limited but creative way, the art world crowd strikes back, trying to mock and abash the government’s attempts at redefining the contemporary art canon.

Seen in this light, the Venice selection of a relative outsider makes a bit more sense. Especially if one takes into consideration a very bizarre official understanding of nationality in Poland, a persistent and perverse inheritance from the times of communism, still in play today. In 2000, in a Note Verbale accompanying the instrument of ratification of the Framework Convention on the Protection of National Minorities, Poland indicated that, “Taking into consideration the fact, that the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities contains no definition of the national minorities notion, the Republic of Poland declares, that it understands this term as national minorities residing within the territory of the Republic of Poland at the same time whose members are Polish citizens”.[9] Therefore, Mirga-Tas will represent Poland as a Polish citizen, and that is that. Move on, folks, nothing to see here.

Yet another possible explanation is the sheer power of Mirga-Tas’s art. Accentuating attachments, family connections, togetherness, and interconnectivity, her work speaks deeply to the sense of emotional disenfranchisement that pervades contemporary societies. As it happens, this very sentiment of torn bonds and emotional lack is one of the key affective chords struck by the current Polish pro-family turbo-conservatives. The wonderful, rich and amazing art of Małgorzata Mirga-Tas may just as well have pierced through to the most hardened hearts of the government officials (it most definitely pierced through to mine). Her depictions of family bonds, rendered tangible with shared pieces of clothing and other objects, or even shown in a literal way, as ropes[10] – demonstrate the possibility that, serendipitously, just reverberated with the family-first ideology of the contemporary nationalists.[11]

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas: Romnija Siwen / Sewing Women, 2021, textile. Photo: ERIAC

So what has the Polish government done, exactly? Has it provided the Roma people with the much needed space of representation, out of the goodness of their hearts? Has it hijacked the Romani identity using a vehicle of Polish citizenship? Or has it committed not just cultural, but worse: an ideological appropriation?

Mirga-Tas’s presence in La Biennale is great in and of itself, as a great artist will meet a great audience. However, this either leaves Poland without its representation, or it offers a distorted image of Poland as a site of hospitality and inclusion. This also raises questions, not only in regard to the “benign nationalism” of the international community, or to the blurry definition of ‘nation’, on which hangs so much.

The problem is: we will never really know, as there is no place, no space for discussion as equals. As long as the Roma people can only represent themselves, so to speak, in passing, there is little chance to achieve a common stance that would be coherent enough and strong enough to demand explanations from the Polish government. Such a demand, however, could originate in RomaMoMA: it would be substantiated by the body of works acquired and displayed in its collection.

Why are we so keen on nations, anyway? Isn’t it time to look around and see that reality has changed, and we are all people, we are all of peoples, and what we need now is not the United Nations, but United Peoples? The Roma could teach just that to the world.

[1] For a detailed vision of the entanglement between national and international, see, e.g.: Sluga, Glenda, Internationalism in the Age of Nationalism, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013.

[2] The Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (FCNM) is a multilateral treaty of the Council of Europe aimed at protecting the rights of minorities. It came into effect in 1998, and by 2009 it had been ratified by 39 member states. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Framework_Convention_for_the_Protection_of_National_Minorities (accessed 6 December 2021).

[3] Council of Europe, Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights: “Legal situation of the Roma in Europe”, 19 April 2002, https://assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/X2H-Xref-ViewHTML.asp?FileID=9676&lang=EN (accessed 21 November 2021).

[4] “The Future of Our Struggle”, 19 July 2021, Romanistan.com, https://romanistan.com/243-2/ (accessed 21 November 2021).

[5] Council of Europe, European Convention on Nationality, Strasbourg, 6.XI.1997, https://rm.coe.int/168007f2c8 (accessed 21 November 2021).

[6] Rizova, Polly and John Stone: “Race, Ethnicity, and Nation”, Oxford Research Encyclopaedias, 11 January 2018 (26 April 2021), https://oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.001.0001/acrefore-9780190846626-e-470 (accessed 21 November 2021).

[7] Polish Pavilion in Venice, Competition – 2022 – Information, https://labiennale.art.pl/en/competition/ (accessed 21 November 2021).

[8] Majewska, Ewa: Feminist Antifascism: Counterpublics of the Common, New York: Verso, 2021, p.20.

[9] Council of Europe, Reservations and Declarations for Treaty No.157 – Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, Status as of 21/11/2021, https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list?module=declarations-by-treaty&numSte=157&codeNature=0 (accessed 21 November 2021).

[10] See Szymański, Wojciech: “Dismantling ethnography, decolonising the museum, flipping the map:

Wesiune thana / Place in the Woods by Małgorzata Mirga-Tas” (https://eriac.org/dismantling-ethnography-decolonising-the-museum-flipping-the-map-wesiune-thana-place-in-the-woods-by-malgorzata-mirga-tas/).

[11] For more on that, see: Graff, Agnieszka and Elżbieta Korolczuk: Anti-Gender Politics in the Populist Moment, London: Routledge, 2022.

[…] Previous Blog Entry […]

[…] Next Blog Entry […]