Identity, Representation, Participation, and Performativity in Nihad Nino Pušija’s Photographs

Nihad Nino Pušija, from the series “Gladiators”, Rome, 2011

Encompassing the complexity, versatility, and resourcefulness of the artistic opus of Nihad Nino Pušija is next to impossible in a single text. What makes Pušija’s over thirty-five-year professional artistic career difficult to embrace in any general overview is his use of a wide range of media, his engagement in different topics, motifs, and art genres, and his address of various contextually relevant socio-political positions. Here, I suggest focusing on photography as the most central medium of his art practice.[1] In particular, I will look at his photographs of and with Roma communities – and I would like to narrow the diverse ethical and aesthetic issues by examining how Roma ethnic identity, representation, participation, and performativity intersect in several of Pušija’s numerous photographic series.

I would like to argue that even though the representation of the photographed subjects is at the centre of Pušija’s images, the typical identity-based photographic representation is mediated and intercepted through his community-based artistic practice and his subtle participatory-focused strategy. Not only does this enable the artist to circumvent the stereotypical representational tropes – often circulated and perpetuated precisely through photography, but it also leads to a certain elevation of political awareness of the problems with representational policies long in place. Pušija uses photography to conceptualise and encapsulate his aesthetic interests, and to achieve his carefully scripted socio-political aims, such as empowering and ennobling his Roma peers, friends, neighbours, or accidental passers-by, who are the subjects of his images. Thus, his photographs invoke agency to unleash the potentialities for dismantling the reproduction of stereotypical imageries.

The challenge of the objectivity of photographic representations of different subjects, objects, images, and various social phenomena in Pušija’s projects is based upon and developed around singularity, specificity, and universality. Here, I refer to singularity and specificity in contrast to universality, and to the complex ways these concepts are interwoven and mutually affect each other in the context of postcolonial theory.[2] Pušija’s work achieves this through a kind of painstaking photographic research of the local communities, and individual Roma micro-histories, in the context of the international political conditions. Thus, he challenges the stereotypical representation of Roma that has been based on long-term simplifications and generalisations. He fights the established social “order” by calling for changes in the (self-)perception and representation of Romani subjects who belong to different generations and cultures – by reflecting on certain urgent socio-political and economic issues – from the position of a contemporary art practitioner. The refugee crisis, slavery, labour, crafts, social insecurity, sexuality, and other issues that are important for the disenfranchised Roma communities and individuals are interlaced with their successful stories, like sets of yarns of different colours and thicknesses. In various photographic series, not only do such stories read as moving reports and testimonials of others, but they often reflect Pušija’s own Roma background and experiences, and they all weave a certain tapestry as warp and weft.

It wasn’t until Pušija moved to Germany (to Berlin in 1992) that he became aware of his ethnic background, and eventually started to self-identify as a Roma.[3] Any self-identification, self-determination, and subjectivity-construction processes begin with the decision – and the right – to use the ethnic name. “Roma” serves as an umbrella term for many different names that various Roma communities use for self-designation. There is a plethora of issues and conditions that surround and determine the use and decision of who has the right to choose and decide the position towards the use of the name Roma – from which Roma could utter their statements of belonging, or non-Roma could act as agents of empowerment and solidarity with Roma.[4] The arbitrariness, and yet a wider agreement behind the term Roma, was one of the first important widely-agreed political decisions and solidarity actions in the history of Roma activism that needs to be cherished and celebrated for its political empowerment, precisely because the Roma differ among themselves, and because the term supplements and even surpasses the linguistic and cultural meaning.

Regardless of the agreement on one common name, there is no one Roma language or ethnicity. In spite of this, the laziness to learn and distinguish ethnic and cultural specificities and differences often results in clinging to the inherited derogatory terms, and generalised stereotypical images of Roma. The concept of identity and the ability to define and understand the points of intersection between different identities and their relationship with collectivity and community has long been a stumbling stone among philosophers and social and political scientists, in any case, due to their different understanding of the status of the human subjects’ social and conscious experience. For example, the dangers behind the homogenisation of such terms come from the inevitable contentious effects of the “ideal of community”, as in Iris Marion Young’s terms: “The ideal of community, finally, totalizes and detemporalizes its conception of social life by setting up an opposition between authentic and inauthentic social relations. It also detemporalizes its understanding of social change by positing the desired society as the complete negation of the existing society. It thus provides no understanding of the move from here to there that would be rooted in an understanding of the contradictions and possibilities of existing society”.[5]

According to André Raatzsch, the importance of Pušija’s photographs is exactly his reference to the “complexity of ethnicized definitions of identity, national affiliation, and simultaneous hybridities”, particularly in “the culture of ex-Yugoslavia and Germany – in a much more ‘honest’ manner than is the case in ‘traditional’ representations of Roma people”.[6] In the project, 50 Photographs without Anti-Roma Racism (50x Fotografien ohne Antiziganismus), Pušija stages seemingly estranged (as in Victor Shklovsky’s ostranenie) compositions of unlikely encounters of Roma persons. However, such encounters look unlikely only to a Western gadji (not Roma) exactly because they interrupt and deconstruct the expected, stereotypical representation of Romani identity.

The process of individuation is never concluded, since – according to Gilbert Simondon – the multiplicity of the pre-individual can never be fully translated into a singularity; whereas the subject is a continuous interweaving of pre-individual elements and individuated characteristics.[7] The only way to defeat imposed identities that oppress us is to free our sub-individualities and combine them with others to form a multitude of possible and potential multiplicities. Multiplicities thus formed will always be “greater” than the society of control, in that each of us is greater than any individual or collective label or name that might be assigned to us (‘man,’ ‘woman,’ ‘student,’ ‘lesbian,’ ‘White,’ ‘Black,’ ‘Roma’), because we are, each of us, more than the names we are given, and often our “names” are misleading.

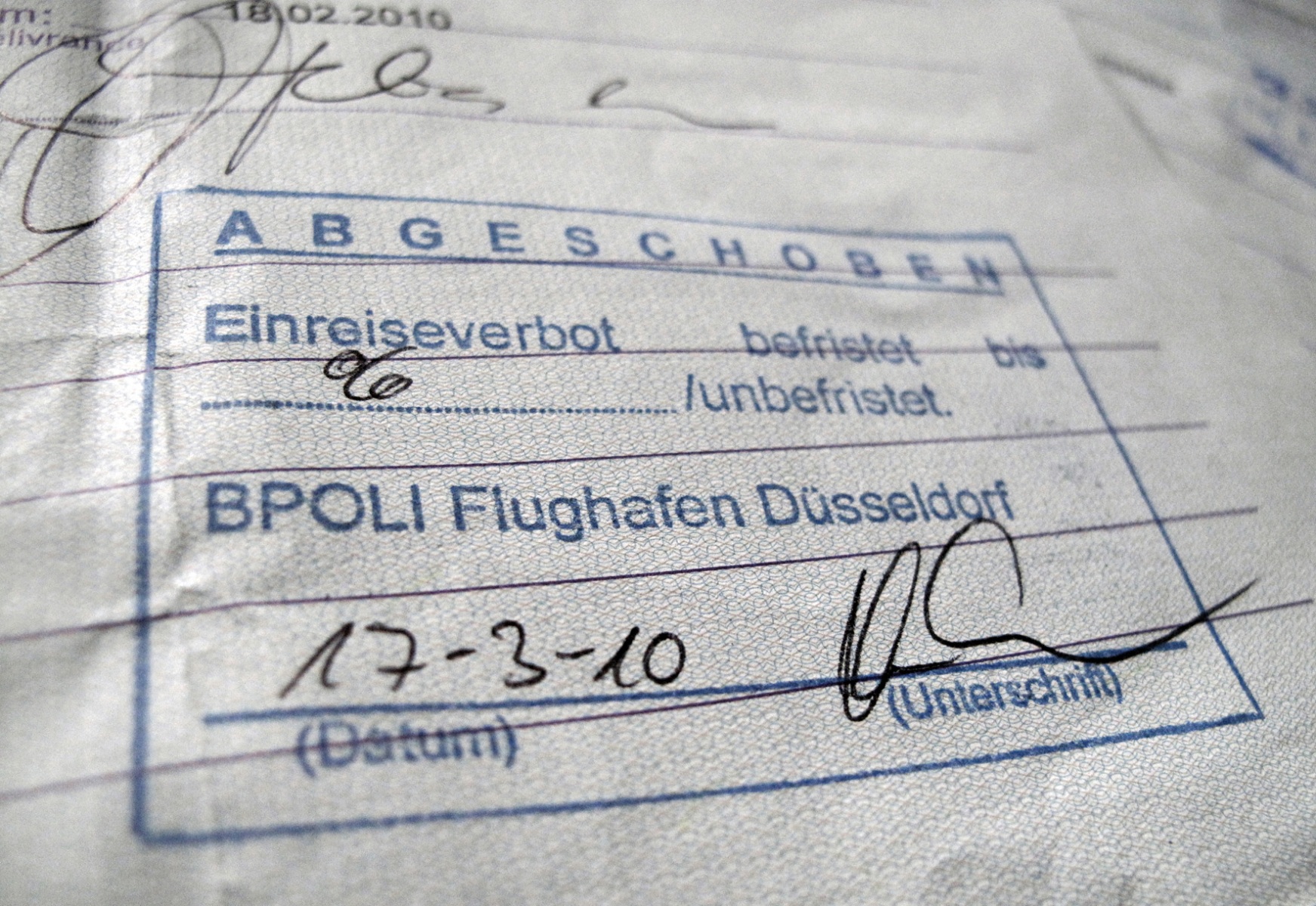

Pušija’s project, entitled Duldung Deluxe (Toleration Deluxe)[8] reflects on the complex issue of the protocols of official identification. It deals with the German document, Duldung[9], which grants a “temporary waiver of deportation”. In its name, Duldung, the document claims “toleration”. More precisely, Duldung refers to the partial permit introduced in Germany in 2009. According to the German residency laws, Duldung (“Tolerated” Status) is defined as a “temporary suspension of deportation”.[10] Exactly this term is, however, directly associated with a kind of non-tolerant socio-political phenomenon that in the 2000s put all Roma in one common identity-based “bag”.[11] The project referred to the persecution of Roma in several EU countries in the recent past (e.g., in France and Germany), following the split of the former Yugoslavia. The German government signed a repatriation agreement to deport up to 14,000 refugees to the successor states of the former Yugoslavia, resulting in the deportation of Roma teenagers and young adults from Germany to their countries of origin, such as Bosnia, Serbia, and Kosovo.[12]

The series of passport photographs, Duldung Deluxe, comprises a series of portraits of Roma holding Duldung. Their testimonies unravel and document the questionable restrictive EU policy towards the Roma as Europe’s largest minority. Even though there was no legal proof of discrimination, half of the Roma deported after 2009 were children who had mostly been born and raised in Germany – and had no home elsewhere. The photographs of real Duldungs are accompanied by the individual biographical micro-narratives of the young Roma who participated in the project. They bear witness to being deported from their country of birth – Germany – mostly to a country to which they never had any personal or cultural links, and of which they don’t even speak the language – such as the brothers Prizreni.[13] The personal testimonies of the project’s photographed participants directly challenge and oppose the deportation authorities’ macro-narrative of “repatriation”. Therefore, the legal term “repatriation” does not reflect the simple fact that Germany was their home country.[14]

At this point, I would like to pause temporarily and focus on a seemingly unrelated performative image, that of Valentino from the project, Gladiators – a series of photographs realised in Rome in 2011. According to the artist’s statement, the image of the young boy Valentino dressed as a gladiator is a metaphor for a historic event: “The photo shoot took place in Rome about 150 years after the Roma people were freed from slavery”.[15] The artist refers to the act of abolition in present-day Romania, when nearly 250,000 Roma slaves became legally free – after almost 500 years of slavery.[16] Such photographs of young Italian Roma, taken in a gladiator school in Rome and wearing original gladiator gear, convey the empowering story of the full circle of liberation and construct a self-image and subjectivity diverging from the prevailing images of impoverished, silenced, and marginalised Roma.

The symbolism of the performative aspects of “Valentino” and other staged portraits of new Roma subjectivity confirms the assumption that photographic stereotypes and racism are not necessarily embedded in photographic representation. However, such limitations still prevail elsewhere, as already argued by Juliane Strohschein in her text about the specificity of Pušija’s photographs, since technological and societal rules are inherited and embedded through education, institutional structures, and other cultural regimes of representation that promise certain “empirical truth accessible through visual evidence”.[17]

Nihad Nino Pušija, Dino, from the series Duldung Deluxe, Bremen, Germany, 2009

The “consumption of photographic imagery” and its wide distribution have disadvantages, as Jonathan Crary clearly stated in his critique of the positivistic assumption that technological devices only enable societal advances. His well-known critique confirmed that there is no such thing as a “neutral eye” – and any supposedly “objective vision” has long embodied structurally and systemically determined ideals of objectivity.[18] In Donna Haraway’s understanding, the problem is that objectivity is understood as impartiality, and a “view from above, from nowhere”, a kind of god’s view and perspective that under the guise of neutrality, or nowhere (but embracing all), hides specific position (male, white, heterosexual, human) and thus makes this position seemingly universal.[19] Furthermore, according to her call for situated knowledge and specific research, the myth of “pure” vision “is always a question of the power to see – and perhaps of the violence implicit in our visualizing practices”.[20] As eyes are “not passive instruments of seeing”, the photo camera is also not passive and organises the world “technically, socially, and psychically”.[21]

Pušija – alongside Crary, Haraway, and other critics of the misunderstanding of the positivistic technological developments and representational regimes missing on the importance of addressing the hierarchical and discriminatory powers – teaches us that one needs to learn and unlearn how to see, rather than hoping to document the world unmediated – as it “is”. I would like to return to my proposition from the beginning of the text, to look at the participatory artistic research and performative aspects of Pušija’s photographs. I find most important his awareness of the constructivist positionality within the visual field that can defy the embedded essentialisation of representation of identity, and on the way it can dismantle the notion of the photo camera as an imaginary technical device – long wrongly presented as a kind of “neutral eye”. In this respect, I would like to argue that although Pušija’s photographs also seem a “neutral” depiction of reality, his research focuses on the intersection between the urgent political events and subjects’ destinies during which his “participants” co-construct their imagery and stories, and thus become active agents of new knowledge production and creation of new Roma subjectivity.

Undoubtedly, the potentiality of performativity, participation, and agency of self-presentation has been embedded in photography since its outset. However, this does not come by default, and it often generates more harm when it comes from “outside” the community that is researched, and when – unlike in most of Pušija’s projects – the research is not based on profound collaboration and participatory research. The potentiality of staged photographs, performativity, and participatory art is unleashed when the assumed movements towards social change and artistic activism occur only in continuity, and with empathy, compassion, and solidarity that is not performed by the artist and her/his creativity – in a one-way street fashion – but are the result of reciprocal exchange and co-belonging.

Deportation stamp on deportation letter, from the series Duldung Deluxe, Prizren, Kosovo, 2010, ©Nihad Nino Pušija

[1] Pušija began his career as a photojournalist, and he continued using his long-term experience with documentary photography in parallel with his experiments with other photography-based hybrid mediums. He has produced many photo books, booklets in the form of the photo-novella genre, and a form of tourist cards known as “leporello”, or community-based archives, and he is invested in many other projects as a “witness” testifying about the contradictory conditions of Roma communities and professionally successful individuals. For example, see his contribution, Venice Mahala Opus, to the exhibition, Call the Witness: Suzana Milevska, Call the Witness, BAK, Utrecht, 21.05 – 24.07.2011; brochure: Utrecht, NL: BAK, 2011.

[2] Peter Hallward, Absolutely Postcolonial Writing between the singular and the specific, Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2002.

[3] Nihad Nino Pušija is a professional photographer, born in Sarajevo, Bosnia, in 1965. Since 1992, Pušija is based in Berlin. See: Nihad Nino Pušija, Foto Fabrica, http://www.fotofabrika.de/english/vita.html [accessed 01.06.2024]

[4] The term “Roma” was widely accepted after 1971, when during the first truly transnational Roma congress, which took place in Orpington (near London), the Roma activists present agreed on the term to circumvent the derogatory connotation of the labels “Gypsy”, “Zittan”, or “Tzigani”. Later, other groups and ethnicities also began to be added for clarity and respect towards the ethnic differences among the Roma themselves, such as Sinti, Manush, Kalo/Kali, Ashkali, Yenish, Kalderash, the British Travellers, etc.

[5] Iris Marion Young, “The Ideal of Community and the Politics of Difference”, in: Social Theory and Practice, Florida State University, Department of Philosophy, Vol. 12, No. 1 (Spring 1986), pp. 1-26, p. 2.

[6] André Raatzsch, “50 Photographs Without Anti-Roma Racism”, in: Politics of Photography, online project, RomArchive, https://www.romarchive.eu/en/politics-photography/reading-photography/50-photographs-without-anti-roma-racism/ [accessed 01.06.2024]

[7] Gilbert Simondon’s views are discussed in Paolo Virno: A Grammar of the Multitude: For an Analysis of Contemporary Forms of Life, New York: Semiotext(e), 2004, pp. 78-79.

[8] Suzana Milevska, “Rewriting the Protocols: Naming, Renaming and Profiling”, online exhibition, RomArchive, https://www.romarchive.eu/en/visual-arts/subsection-rewriting-protocols/rewriting-protocols-naming-renaming-and-profiling/#fn8 [accessed 01.06.2024]

[9] Nihad Nino Pušija, “Duldung Deluxe Passport: On the ‘toleration’ and deportation of Roma youth and young adults in Germany”, in: Lith Bahlmann and Nihad Nino Pušija, Duldung Deluxe Passport, Berlin: Archiv der Jugendkulturen Verlag KG Berlin, 2012.

[10] One of the more precise definitions of “Duldung” was published in the online book, Not Safe At All: “It relates to foreign nationals whose asylum application has been denied, but who cannot be deported due to legal, humanitarian, medical or other issues. It is therefore not a status granting legal residency, but only a confirmation of registration with the authorities, which is re-examined every one, three, or six months. Persons with this status are subject to severe restrictions, e.g., they are not allowed to work and can’t move freely beyond the federal state in which they are registered”. See: Not Safe At All. The Safe Countries of Origin Legislation and the Consequences for Roma Migrants, edited by Wenke Christoph, Tamara Baković Jadžić, and Vladan Jeremić; authors: Wenke Christoph … [et al.]; translation: Lydia Baldwin. Belgrade: Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung Southeast Europe, 2016, p. 70. https://rosalux.rs/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/099_not_safe_at_all_wenke_christoph_et_al_rls_2016.pdf [accessed 01.06.2024]

[11] § 60a Residence Act (AufenthG) indicates which deportation orders can be temporarily waived and replaced with “toleration” (§ 60a Para. 4 AufenthG) and criminal liability for an “illegal” stay, according to § 95 Para. 1 Nr. 2 AufenthG, is no longer applicable. According to Lith Bahlmann’s 2012 text about the Duldung Deluxe Passport project, this number included some 10,000 Roma. See: Lith Bahlmann and Nihad Nino Pušija, Duldung Deluxe Passport, p. 3.

[12] Roma from outside the EU are more likely to be provided with “Duldung” status rather than a more durable status, compared with non-Roma third country nationals, according to a study (“Recent Migration of Roma in Europe”) published by Thomas Hammarberg and Knut Vollebeck, the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities in April 2009. For more details, see: Thomas Hammarberg, “European migration policies discriminate against Roma people”, Commissioner for Human Rights, Strasbourg, 22.02.2010, https://www.coe.int/be/web/commissioner/-/european-migration-policies-discriminate-against-roma-peop-2 [accessed 01.06.2024]

[13] Op.cit., Lith Bahlmann and Nihad Nino Pušija, 2012, p. 49.

[14] Roma children were thus deprived of their homes and forced back to their predecessors’ nomadic lives – although this was neither through their own volition nor their preference, thereby perpetuating the long-lived myth of the Roma’s exotic existence and common stereotypical image.

[15] The project was exhibited at the 2nd Roma Biennale (initiated by Damian Le Bas, and curated by Delaine Le Bas and Hamze Bytyçi). See Nihad Nino Pušija, 2nd Roma Biennale, https://roma-biennale.com/artists/nihad-nino-pusija/ [accessed 01.06.2024]

[16] Slavery persisted on the territory of present-day Romania, at least from the founding of the principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia in the 13th-14th centuries. The majority of the slaves were of Romani ethnicity. Slavery was abolished only in the nineteenth century with the Romanian War of Independence and the formation of the United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia in 1859. In 1843, the Wallachian state freed its slaves, and in 1856, slaves of all classes were freed after the legislation drafted by the lawyer and historian Mihail Kogălniceanu. See Slavery in Romania, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slavery_in_Romania

[accessed 01.06.2024]

[17] Juliane Strohschein, “The Canon Of Images: How Is Structural Racism Embedded In Photographs?” in: Politics of Photography, https://www.romarchive.eu/en/politics-photography/politics-photography/bilderkanon/ [accessed 01.06.2024]

[18] Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer on vision and modernity in the nineteenth century, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999, p. 16.

[19] Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective”, in: Feminist Studies, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Autumn, 1988), pp. 575-599, p. 589.

[20] Ibid., p. 585.

[21] Ibid., p. 583.

_______________________

This text was originally published in the monograph Nihad Nino Pušija: In Search of Eldorado—Roma and Sinti in the Struggle for Representation, edited by Rena Rädle & Vladan Jeremić

Authors: Timea Junghaus, Rena Rädle & Vladan Jeremić, Suzana Milevska, André Raatzsch & Emese Benkö, Moritz Pankok and Hedina Tahirović-Sijerčić.

Layout and design: škart

Size: 25 x 35 cm, 305 pages, ISBN: 978-3-9822573-6-5

The publication has been made possible through the support of Hauptstadtkulturfonds (HKF), the Berlin Senate Department for Culture and Social Cohesion.

_______________________

Suzana Milevska is a curator and theorist of visual cultures. Her theoretical interests include postcolonial and feminist critique of hegemonic powers’ representational regimes, and collaborative and participatory art practices in solidarity with marginalised and disenfranchised communities. Milevska was the first endowed professor of Central and Southeast European Art History at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. She has curated numerous international exhibitions focusing on community-based projects, such as Roma Protocol (Austrian Parliament, Vienna, 2011), and initiated the project Call the Witness (BAK Utrecht and Venice Biennale, 2011). Milevska holds a PhD in Visual Cultures from Goldsmiths College London. In 2012, Milevska was awarded the Igor Zabel Prize for Culture and Theory.

Leave a Reply