Bravo, Barvalo! Pioneering Participation, Curatorial Courage, and a New Approach to Roma-Driven Museum Projects

Dylan Schutt, Anna Mirga-Kruszelnicka, Julia Ferloni, Zeljko Jovanovic receiving Prix Historia for Barvalo, 13 November 2023, @Mucem

The summer of 2023 saw a true landmark accomplishment in the promotion and celebration of Romani art and culture. The Barvalo exhibition, on view 9 May until 4 September at Marseille’s Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Mediterranée (“Mucem”), a Tier-1, national-level French museum, was the first of its kind: by far the largest and most visible museum project ever focused on Romani people, and likewise the only participatory, collaborative, Roma-driven, Roma-centred museum exhibition ever to be mounted at such a scale. And thus it was pioneering not only in what it was, in its content, but in its form, in the fact that it was Roma-driven, and Roma-driven at the global scale at a major national museum.

Here is a summary of Barvalo’s impressive accomplishments, in numbers:

- 100,279 visitors

- 103 days, in duration

- 964 visitors per day, on average

- 17 collaborative seminars or webinars with the committee of experts and the curators

- Some 1,000 visitors, or approximately 1% of the total visitorship, wrote a comment in the guestbook

- 77 objects collected across 12 fieldwork projects (enquêtes-collecte, including in Spain, Turkey, France, Romania, Hungary, and the United Kingdom), of which 38 were acquired and added to the museum’s collections, with more to come (see the previous article by Françoise Dallemagne, Alina Maggiore, and Julia Ferloni, May 2023, to this point)

- 65 works of contemporary art, along with a host of other objects, were acquired and added to the museum’s collections

Today, on the day of this posting, Barvalo has been awarded The Historia Prize for the best museum exhibition of 2023, an achievement none of our team could have dreamed of years ago, in the project’s early days, as the idea came to life and first took shape.

The idea for Barvalo was born as early as 2014, when, living in Marseille and doing ethnographic research funded by the US National Science Foundation, I first visited Mucem’s permanent exhibition halls. There I noted a total absence, in galleries whose purported purpose was to represent in broad brushtrokes the manifold peoples of the Mediterranean rim and their histories, of any mention of Roma, an all-too-common, all-too-old, and non-incidental omission that articulates with larger epistemological exclusion. When I learned that no project substantially using Romani material had ever been undertaken by Mucem, I felt this lacuna had to be rectified, discussed, and addressed in the name of recognition and representation, and to play a role in countering acts and patterns of exclusion that render Roma people invisible.Representational exclusion forms part of larger structures of racism, material and semiotic alike, as does authorial exclusion: all too often, texts, narratives, and exhibitions “on” Roma have been created without any involvement or direction by Roma people, and thereby narrated entirely by outsiders, often feeding directly into stereotypes—including Orientalist, romantic, and exotic distortions—and always playing into the marginalization of Roma from the process of creating representations and narratives of Romani history, society, art, and innovation. Indeed, in these outsiders’ representations, Roma are often presented as possessing no culture, art, or innovation, and, in the relevant imagery, as living lives only of poverty and misery. To make matters worse, an objectification of Romani bodies is too often paired with these presentations, as if two sides of the same specious truth. ERIAC’s curatorship of Barvalo thus addressed an urgent need for universal Romani authorship of public projects on Roma, and came at an opportune time. It also embodied a bold stand against recent museum and media projects about Romani lives prominently featuring the timeworn tropes, falsehoods, and failures that have marred Romani representations more broadly. Barvalo was doubly pioneering in the French institutional landscape, where in official contexts discussions of ethnolinguistic identity are proscribed; to have a major French museum take this on, especially with community authorship, was a watershed moment, a pivotal step, and perhaps part of a sea-change.

Never before has a single exhibition about Romani history, culture, and art had such exposure, much less one curated and authored by Romani voices. Barvalo, as mentioned in the numbers above, received more than 100,000 visitors and was covered by news media across France, won the attention of scholars and dignitaries, and was embraced by Romani communities. On its opening nights, the exhibition was so popular that the museum was kept open beyond the normal closing time to accommodate the visitors. Throughout its tenure, the exhibition had queues down the hall and around the corner.

Barvalo represented a tripartite partnership, on its curatorial team, between ERIAC, Mucem, and myself. The Mucem team was represented by Julia Ferloni, Françoise Dallemagne, and Alina Maggiore, and ERIAC by Deputy Director Anna Mirga-Kruszelnicka and Director Timea Junghaus. In terms of Romani representation in form, process, and content, a Romani curatorship was critical, but the team sought to go still further, even from the project’s inception, and our ethical commitments demanded that we apply additional rigorous standards: we formed a “Committee of Experts”, fourteen strong (though varying in number over the life of the project), many of whom were Roma, along with an outer circle of many other experts of international renown. These experts guided and authored content on a far-ranging set of questions, from language to terminology, history to music, and deepened the network of community contacts and connections with whom we were able to work.

Nor was even all that enough: we felt the content needed to go beyond a conventionally static and teleological display of art and artifact, and we endeavoured for Romani voices—in the literal, palpable sense—to contribute to that objective. Through our experts and their networks, we identified four people from diverse Romani communities around France to be “present” in the exhibition hall as “guides” through the exhibition: their stories—penned by them and presented in short videos—were interspersed throughout the exhibition, in every section, where they shed light upon, and humanized, the Romani past and present in their own words. Not unrelated to this were the fruits of our commitment to featuring and providing as much Romani-language content as possible; to this end the exhibition catalogue was fully translated into Romani, as were all of the major gallery texts. This had the double benefit of making a statement about Romani and enhancing linguistic access.

The project sought a balance between an explicative and even provocative illumination of Romani history and culture and a revelation of Romani art and excellence, and likewise between that history’s darker moments and the brilliant innovations and creative genius of Romani society expressed through imaginative endeavour and expertise. To that end, even the most “beaux-arts” spaces in the exhibition had at least one work and usually multiple works of modern art in dialogue with and “speaking back” to them. The exhibition contained numerous artistic commissions, works specifically created for Barvalo, all of them by Roma artists; in art as well as in process, the project was thus Roma-driven. The museum itself also dignified the quality of the works by acquiring a number of them into their permanent collections.

The exhibition opened with the Romani deep past, with special reference to language, particularly through a Tree of Languages by Marina Rosselle, as a way of approaching the complex “question of India”; then moved into a section—containing exceptional loans from the Louvre and the Museums of Graz and Dresden—exploring the “fear and fascination” around Romani arrivals in Europe, including the quick emergence of racism, persecution, and enslavement; and continued into a space dealing with stereotypes and exoticism, showcasing the remarkable tapestry (from Mucem’s collection) of Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, featured artist of the Polish Pavilion of the 59th Venice Biennale (2022). From here, the visitor was led into a large gallery treating the subject of the long struggle for citizenship in modern states, featuring three of Kálmán Várady’s exquisite Gypsy Warrior statuettes, currently pending for Mucem acquisition, to put the emphasis on resistance; a wall of blown-up archival anthropometric booklets as required in France from 1912; and works by Marcin Tas and Mitch Miller, now also in Mucem’s collections (or soon to be), among others. A transition to the next section was constituted by Luna de Rosa’s arresting Tree of Antigypsyism, a captivating work in bricolage and deconstruction created—with ERIAC input—during a residency at the Villa Romana di Firenze as a special commission for Barvalo.

Following from Luna de Rosa’s work, the exhibition turned its attention to the Holocaust period, with a triple focus on victims and their suffering, on resistance, and on failures at commemoration, with art by Nihad Nino Pušija, Mucem-acquired photographs by Valerie Leray, and three originals from Mucem’s collections inside a special sanctuary (inside of which visitors heard Santino Spinelli’s “Auschwitz” read aloud in three languages) by Ceija Stojka, alongside many portraits and recorded testimonials. The next space focused on Romani resistance and civil rights, including subsections on environmental justice and feminism, with original documents of landmark moments, images of Katarina Taikon with Martin Luther King, sculpture by Marina Rosselle, and works by Damian and Delaine Lebas, all Mucem-held. From there, the museumgoer was directed through a dark passage—“The Corridor of Antigypsyism”—containing enlarged tweets, news clippings, and political statements of racist intent, alongside other antigypsyist artifacts (such as Romanian carnival masks used by villagers for mocking Roma), to impress upon the visitor the pain of the daily experience of exclusion and hate. This was a challenging section to create, as we were determined neither to give attention to hateful voices nor to reinforce or reify their vicious messages.

The final sections were more positive and sometimes even playful—from the earlier benighted space, the visitor stepped into a brighter gallery in which they would first experience one of the project’s true showstoppers: Gabi Jimenez’s original installation, Le Musée du Gadjo, the Museum of the Gadjo (the Romani term to denote non-Roma). Created as a museum-within-a-museum in the fashion of natural history museums, with their staid dioramas and evolutionary narratives, Gabi’s raucous space is simultaneously a comment on museums, a comment on race in museums, and, above all, a comment on the Romani experience of being (mis)represented. What, asks Le Musée du Gadjo, is it like to see yourself distorted, presented and recounted by outsiders for outsiders, with wrongheaded explanations and narratives of who you are? What is it like to have society decide what you are without any consultation from you, or even any knowledge of you whatsoever? By showing the typified or rather stereotypified Homo gadjensis a twisted and hilarious museological representation of themselves as imagined by a Romani artist, Gabi—who said on opening night “it only becomes a work of art when you step in it”—allowed gadje to have this experience themselves.

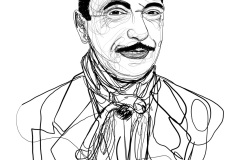

From here, the visitor exited to a large gallery showcasing excellence and innovation in Romani arts and culture, and major contributions to European and world society, with objects such as Django Reinhardt’s last guitar, jewellery by Rosa Taikon (now in Mucem’s collections), original prints by Helios Gomez, and, in a special commission, a kind of “Wall of Fame” created by Emanuel Barica, covered with his signature portraits of some of history’s great Roma people. Here, one could also listen to a tailor-made playlist of Romani music, admire Mucem-held masterworks in copper by Victor Clopotar and a gown by Romani Design, and consider Romani prowess in sports. Just before the museum’s exit stood a condensed version of ERIAC’s nomadic RomaMoMA library project, highlighted by Roma artist Daniel Baker’s table, where the public could sit and read Roma-focused works.

Our commitment to a Roma-driven project didn’t stop there, at the exit to the show, nor was it limited to what lay within the museum’s walls: the exhibition was not just community-centred on the “input” end, but also in the “output” experience. We aimed for something dialogic. A conversation. For that reason, the Barvalo team worked with countless schools, organisations, associations, movements, and networks, on every scale, from the most local to the truly global. Romanian Roma from a small town north of Marseille (Gardanne) had an intensive visit and underscored that they’d had a transformative experience. Middle schoolers from the town of Orange who worked on the content throughout their academic year came and made a presentation in the gallery, and a second set from Marseille’s Rosa Parks school, many of them Roma, were able to pair their curriculum with Barvalo. Our experts brought in hundreds of Roma community members to hear their thoughts. Roma people from a region to the west of Marseille crafted a woven tapis in partnership with the exhibition that they toured in five localities, as ambassadors to Barvalo, and as a means by which to encourage Roma to come see the exhibition. Numerous schoolteachers working with Roma youth came to receive training from our curatorial team and deliver their new knowledge to classrooms. And a group of some twelve twelve-year-olds worked intensively through their semester on the concept of a museum, the idea of an exhibition, and the challenges of fashioning a museum project about Roma, with Roma, and by Roma. Those young people were able to come to the museum many times to learn about its workings, to meet curators, to visit with Romani artistic leaders—like actor and filmmaker Alina Șerban—and other dignitaries on the opening night, and to come away feeling like stakeholders. For me, this was one of the most critically important, and potentially the most lasting, facets of this project.It is not only process—and not only expert and artist input—but also the visitor and audience experience, that is worthy of attention, as regards Barvalo. What did audiences come away with, how did they react, what did they learn? Near the exit of the exhibition, a digital livre d’or, a guestbook, was provided. Mucem fastidiously studied what was entered into the guestbook, including in order to explore racist reactions and presuppositions that might have played into the exhibition experience. Surprisingly, such reactions were relatively rare. This guestbook was very carefully followed and analysed to try to get a sense of what visitors thought, felt, and understood, as they transited the space. The curatorial team and experts were very pleased to find that visitors reported an enriching, powerful, and positive experience, including a sense of revelation and deep gratification, with comments like Bravo! This opens your eyes, moves you, scandalizes—thank you for this exhibition. One Romani visitor wrote, This permitted me to reconnect to my culture. Another: I’m ten-years-old and of Romani [Gitan] origin and I find this so interesting and instructive. A second source of feedback came from a survey on visitors’ emotive and affective responses to the exhibition (carried out by Lena Chaber). Here, a different side of visitors’ experiences came out—one that revealed to us the degree to which the exhibition moved visitors, largely (if not uniformly) worked towards shattering stereotypes, and engendered a sense of injustice. And indeed, on more than one occasion, I had visitors stop to tell me such things—sometimes in tears.

The project enjoyed fabulous press coverage, with in-depth description, dedicated interviews, and serious critical analysis, in all media—print (including magazines and newspapers), television, radio, and internet, with international presence in such outlets as The Times of London, Barron’s, The New York Times, and The Economist, along with nearly every major French periodical and TV station, from Le Monde to TV5. It was featured in podcasts and special episodes. It was also studied by museum researchers, including graduate students, postdocs, and tenured faculty, particularly for its participatory approach, from around the world – as far away as Japan and Australia. Moreover, a range of dignitaries, including several inter-ministerial delegates, other European countries’ members of parliament, and the French first lady, Brigitte Macron, came to see Barvalo, all constituting a sign of how seriously the show was taken in official circles, as in unofficial ones.

If this all sounds very rosy, it should of course be mentioned that the experience was not without challenges and shortcomings. The press was not always sufficiently inclusive and representative. The final outcomes could not always satisfy all of our visions. Constraints were plenty. Budgets were sometimes limited, and some pieces of the original concept had to be left behind. Certain topics were under-treated. As a fly-on-the-wall, walking through the exhibition, I could on occasion hear disparaging remarks by visitors; this is to say that racism, alas, persists nonetheless, despite vigorous efforts to the contrary. And Barvalo has not yet had a major “tour”, a fully-linked major project in another museum. Challenges notwithstanding, we feel quite strongly that the project was a success, as did those many Romani community members who came to see Barvalo. And, while racism remains, one can, by such efforts, make a difference, and defy it. This project made a major statement and delivered powerful messages. I would like to see Barvalo reiterate or reincarnate, and to evolve with modifications to form, in a context that gives it the space to live again and live longer, to take on some form of permanent presence, whether this be a permanent installation in a French museum, even Mucem itself (noting that Gabi Jimenez’s painted guitar, Ne Me Tuez Pas [Do Not Kill Me] will now form part of Mucem’s permanent exhibition); an entrenchment in French and other European school curricula; or the development of some kind of series. To see Barvalo have a sustainable and lasting form is a dream and an aspiration, and I think it holds the potential for serious impact.

The Barvalo project and all of those involved in its creation resolved to say to France, to Europe, to museums in general, and to the world: when it comes to public presentation of Romani lives, experiences, stories, histories, and art, this is how it is going to be from now on, in order to create a model, a blueprint, for inclusive, participatory, engaged, collaborative, and community-invested presentation of Romani life, cultural production, and experience. It is not enough to let it stop here. The next step is to do it again, and to keep on doing it. As Emanuel Barica proudly said before his wall of portraits on Barvalo’s opening night: Opre Roma!

Leave a Reply