Sead Kazanxhiu’s The Nest: Making Space and Envisioning Agency for Marginalised Cultures

Sead Kazanxhiu: The Nest, 2012–2022, installed on the façade of the Fridericianum at documenta fifteen. © documenta and Museum Fridericianum gGmbH, photo: Nicolas Wefers

At documenta fifteen, five massive swallow’s nests have appeared on the façade of the Fridericianum. Emerging from its walls between the engaged columns of its southeastern wing, the rough surfaces and organic forms of the five polymer structures that comprise Sead Kazanxhiu’s The Nest at once challenge and compliment the Fridericianum’s neoclassical monumentality. These nests suggest a transformation in the museum’s structure, an interpolation of new and unorthodox spaces that promise a more inclusive vision of the cultural institution, one that can be occupied by historically and politically marginalised cultures. These new elements reference the architectures of the nonhuman world, transforming the institution into a hybrid space that symbolically includes the natural as well as the cultural within its purview. At the same time, the marked aesthetic contrast with the façade asserts the need to acknowledge and preserve positions of cultural difference, to avoid the myth that assimilation can solve problems of inequity and historical injustice.

Sead Kazanxhiu’s The Nest is a potent metaphor for the creation of new spaces of encounter and new economies of attention, the acceptance of new traditions of knowledge, and the establishment of new networks of care. In this sense, the work fits logically within the curatorial framework established by documenta fifteen’s artistic directors, the Jakarta-based collective ruangrupa, who have conceived the exhibition as a site for collectivity and the sharing of resources. Born in 1987, in the village of Baltëz, near the southern Albanian town of Fier, Kazanxhiu works across installation, performance, sculpture and painting. His works persistently raise questions about borders, structures, space and identity—about the ways that our conceptions of the world, our feelings of being included or excluded, and our capacity for understanding shift in response to new delineations and distributions of space. Sometimes his investigations navigate the framework of his own identity as a Roma artist living and working in Albania, but at other times (as in the case of The Nest) they move beyond his specific situation to reflect a broader critique of institutions and their practices of inclusion, exclusion, and knowledge production.

Kazanxhiu’s work—with its concern for the politics of belonging and its persistent attention to those who are left out of processes of decision-making and institutional direction—resonates strongly not only with the overarching themes of this documenta edition, but also with the goals of RomaMoMA (a project initiated by ERIAC: European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture and OFF-Biennale Budapest), which aims to transnationally and performatively think about the possibility of an institution dedicated to Roma contemporary art. RomaMoMA was given the opportunity at documenta fifteen to present a survey of work by Roma artists, of which Kazanxhiu’s The Nest is an important element, reflecting a timely and engaging approach to the transformation of cultural institutions, including the museum, the gallery, and, of course, the large-scale international exhibition.

The Nest, like many of Kazanxhiu’s interventions in public space, challenges us to think about the boundaries that institutions establish, boundaries that not only limit participation, but also limit our capacity to imagine a decolonised future.[1] What can we do to bring about a more equitable inclusion of marginalised cultures in social and political decision-making processes? In a pragmatic sense, how can we acknowledge institutions and work within them, while still holding on to a vision of radical change—a vision of a future that explicitly acknowledges systemic injustices and works consistently to undo them and to mediate their affects? Most crucially, how can we act collectively to accomplish these changes, without losing our connections to particular communities, or falling prey to the emphasis on individuality that characterises neoliberal capitalism?

Kazanxhiu has approached these questions in various ways in his prior work, investigating his own capacity to act in both an artistic and a political sense within Albanian society. In 2013, Kazanxhiu created 8 for the 8th of April, a public work in which he blocked the entrance to the Albanian Parliament with eight large tractor tires painted in red, green, and blue—the colours of the Roma flag. This disruption of the entrance to an official space was a playful intervention, but it also possessed an immediate symbolic impact, drawing attention to the lack of involvement of Roma people in public institutions in Albania. The following year, with the project Shtepizeza (Little Houses), Kazanxhiu again occupied an open space directly related to a major Albanian political institution, this time the sidewalk directly in front of the Albanian Prime Ministerial building. There, together with supporters, he placed a multitude of small plaster sculptures of houses—in a spectrum of pastel hues—on the ground, to highlight the dire housing situation for Roma people. Housing security continues to be a major issue in Albania, where neighbourhoods are regularly demolished to make way for new bypasses or for the construction of expensive housing and retail structures.

Sead Kazanxhiu: 8 for the 8th of April, 2013, public installation at the entryway to the Albanian Parliament. Photo courtesy the artist.

The (public) institution and the home: many of Kazanxhiu’s artworks move—implicitly or explicitly—between these two sites of belonging, places where our identities are defined through our collective action with others who help us to construct those spaces. The home can also be defined by absolute boundaries: in On the Wall (2015), Kazanxhiu constructed an artificial enclosure with broken glass bottles along its top edge, a form drawn directly from Albanian private houses, which often feature a garden or patio space surrounded by a wall topped with broken glass embedded in concrete, as a method to deter incursions. This practice frames the home as a space under constant threat, signalling Europe’s constant concern with its own permeability. With I Don’t Have Borders to Protect (2017), Kazanxhiu offered an alternative to the violence of the neo-imperialist mindset and its efforts to sharply delineate territory. This work, created for the first edition of the Autostrada Biennale in Prizren, Kosovo, which featured golden balloon letters spelling out the titular declaration, made a straightforward assertion about the Roma community, which lacks its own definite national borders, while at the same time proposing a future that might exist without such borders entirely, a future of free movement that is also free of nationalistic politics and their divisive ideologies.

These works examine the politics of space, acceptance and access at a scale that implicates larger social bodies (especially the nation), but Kazanxhiu has also investigated the transformation of the personal that occurs as an individual attempts to intervene in and work within institutions to achieve structural change. As an activist for Roma rights in Albania, and a member of Albania’s Committee for National Minorities, Kazanxhiu is also conscious of the importance of holding onto the idealism and radicality that has motivated both his art and his political work. There is the constant danger (as an artist and as an activist) of being commodified by the systems that govern both contemporary art and politics, two spheres that are closely intertwined in Albania. This danger also exists on the scale of the global artworld, where the integration of marginalised voices (such as those of Roma artists) often also affects their co-optation.[2] This is particularly the case as discourse on the relationship between art and decoloniality risks becoming simply trends and buzzwords that conceal the persistent neo-imperialism of global artistic ‘centres’.

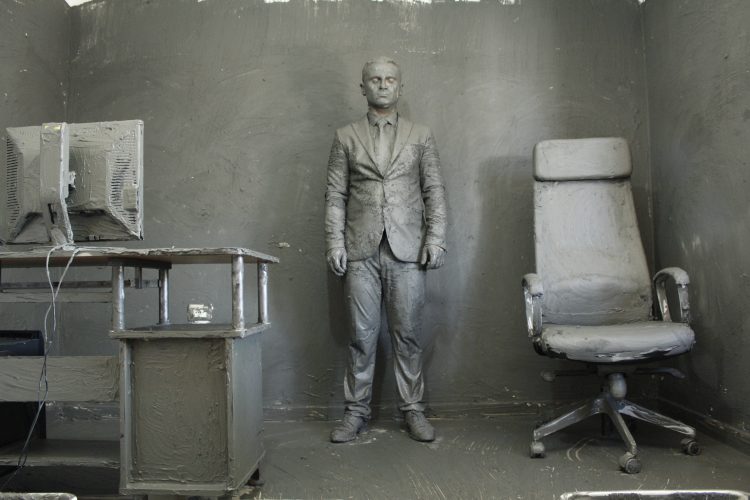

In his performance, A Choice to Be Made, A Price to Be Paid (2015), Kazanxhiu raises the question of the possibility of a ‘Romani land’ (or Romani phuv), a concrete space that might take the place of the ancestral homeland that the Roma people lack. In the performance, he breaks apart pieces of clay and boils them in water, creating a thick slurry. He then changes from his casual clothes into a formal suit, before writing the phrase ‘Romani phuv’ on the wall behind him in clay. The clay that Kazanxhiu uses in the performance is called shishik in the Romani language, and the artist explains that the clay is used by Roma peoples in Albania to clean themselves (in the past, it was also traditionally eaten by pregnant women). Human settlements are kept far away from the clay, in order to preserve its purity, and it is gathered by women in the community who observe special rituals when going to the site of the clay. In 2021, Kazanxhiu made another work incorporating shishik, this one a performance—documented in a video—entitled Baltosje (Mudding, 2021). Here, the artist shows the gathering of the mud, and its preparation by the women of his village. Later in the video, the women cover the artist (again dressed in a suit), together with his desk, his computer, his telephone, and the walls of the room he is standing in, with the clay. In both these works, Kazanxhiu confronts the challenges facing the artist who becomes part of decision-making structures. Through the purification ritual in Baltosje (a term that typically has negative connotations in Albanian politics, the equivalent of ‘being dragged through the mud’), Kazanxhiu symbolically seeks to maintain an authentic connection to culture and community. In doing so, he seeks to overcome the processes of normalisation and co-optation that attempt to translate the input of marginalised people into merely additional evidence for a smoothly functioning democracy, without addressing systemic injustices or historic processes of disenfranchisement.

Sead Kazanxhiu: Baltosje/Mudding, 2021, video documentation of performance and multimedia installation. Video still courtesy the artist.

The Nest also seeks to create new spaces—even new homes—while still preserving the possibility that difference is a foundational element of belonging. When we understand both the home and the institution as a place of difference (within and between ourselves), then we have the potential to incorporate marginal perspectives, without simply homogenising them or erasing their critical potential. The Nest’s appearance in Kassel is not the first time Kazanxhiu has installed his five polymer swallows’ nests on a monumental façade. For the exterior installation of the work, in 2018, he placed the five nests in the gaps between the columns of the Albanian National Historical Museum, beneath the massive and iconic mosaic that graces the front of the building and looks out across the expanse of Skanderbeg Square, Tirana’s central plaza.[3] There, the organic forms of the nests were a direct response to the clean lines and geometric forms of socialist modernist architecture of the museum, and to the narrative and figurative clarity of the Socialist Realist mosaic, which presents a clear (and clearly nationalist) account of the unity of the Albanian people’s identity through the centuries, establishing a continuity between ancient Illyrian peoples and the Socialist society. (The building was completed in 1981, at the beginning of Albania’s last state Socialist decade.) The nests disrupted this monolithic mono-ethnic portrayal, pointing to other identities (including Roma people) who are left out of this national narrative, despite very much having been present in Albania’s modern history.

In Kassel, on the façade of the Fridericianum, The Nest immediately enters into dialogue with the history of that structure, the façade of which has become a paradigmatic signifier of the ‘museum’, despite the fact that it has not served that purpose since the tremendous damage done to the structure during the Second World War. The fact that the Fridericianum, as one of the earliest public museums in the world, has also become a structure associated with contemporary art (first through its role as a venue for documenta, and later through its own exhibition programming) indicates the mutability of the museum as a symbolic space.[4] The Nest appropriates this mutability, testing its limits and disrupting the perceived authority of the institution’s relationship to dominant western narratives of cultural development. In a very basic sense, The Nest creates a new economy of attention. The swallow’s nest not only signals the omnipresence of the nonhuman, even in the most anthropocentric built environments—its appearance also signals a paradigmatic moment of ‘taking notice’. Birds’ nests are elements of our surroundings (especially in urban contexts) that we often overlook: we come upon them suddenly, often when we unexpectedly hear the chirping of recent hatchlings, or notice the flight patterns of birds constantly coming and going from specific overhangs, or when we simply take a moment to look up.

Sead Kazanxhiu: The Nest, 2012–2022, installed on the façade of the Fridericianum at documenta fifteen. © documenta and Museum Fridericianum gGmbH, photo: Nicolas Wefers

The Nest reminds us that even what we perceive as ‘marginal’ has always been there, has always built its own homes and shelters despite the hierarchies that dominate the centre, proposing new ways of belonging and enacting change. Marginalised peoples have always nurtured their own alternative knowledge and ways of being together, and we can still learn from these practices today. Albania is already a peripheral zone within the global geo-cultural networks of contemporary art, and—with only a few exceptions—curators who have approached artistic production in the country have tended to ignore internal cultural and ethnic differences. As a Roma artist, Kazanxhiu’s work emerges from this doubly marginalised space, and attempts to inscribe the acknowledgement of difference not only into the framework of Albanian society, but also into the wider European context, which still struggles to recognise the critical voices of those that western imperialism has historically silenced and subjugated. The Nest proposes the urgency of creating institutions—cultural and otherwise—that do not simply integrate the marginal, but allow its agency to manifest in transformative ways, to nurture new structures of care and justice. In the context of documenta fifteen, The Nest is a call for new institutional futures, for a new framework of memory and a new way of building together.

[1] On the relationship between Roma artistic praxis and decoloniality, see Timea Junghaus: “Roma Art: Theory and Practice”, in: Acta Ethnographica Hungarica, 59:1 (2014): pp. 40-41.

[2] Daniel Baker and Maria Hlavajova: “We Roma: Notes from a Conversation”, in: We Roma: A Critical Reader in Contemporary Art, Daniel Baker and Maria Hlavajova eds. (Utrecht: BAK, 2013), pp. 30-31.

[3] On this installation of Kazanxhiu’s nests, see Marko Stamenković: “Sead Kazanxhiu: Foletë”, November 2018, https://www.academia.edu/37850202/SEAD_KAZANXHIU_FOLETË

[4] Kathryn M. Floyd: “The Museum Exhibited: documenta and the Museum Fridericianum: Connecting Gaze and Discourse in the History of Museology”, in: Images of the Art Museum, Eva-Maria Troelenberg and Melania Savino eds. (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2017), pp. 65-67.

Text by Raino Isto

[…] Next Blog Entry […]

[…] Previous Blog Entry […]